Fall 2007

American Black Sheep

– Jeremy Lott

Historian Nancy Isenberg argues that "everything we know about Aaron Burr is untrue."

Aaron Burr—grandson of the preacher Jonathan Edwards, distinguished veteran of the War for Independence, and our third vice president—was one of the United States’ great villains, an American Napoleon whose ambition knew no bounds, a lady-thrilling Lothario, a modern Catiline who plotted against the Republic.

Such, at least, was the popular reputation of the man among his contemporaries, and it’s the view that has endured to this day. But, writes University of Tulsa historian Nancy Isenberg, "everything we thing we think we know about Aaron Burr is untrue."

Even granting the author some dramatic license, that’s a provocative statement. Isenberg describes Burr’s rise—from an ambitious young New York lawyer and assemblyman to state attorney general to U.S. senator to vice president—with an eye toward Making a Point. What results is a mix of great biography and special pleading.

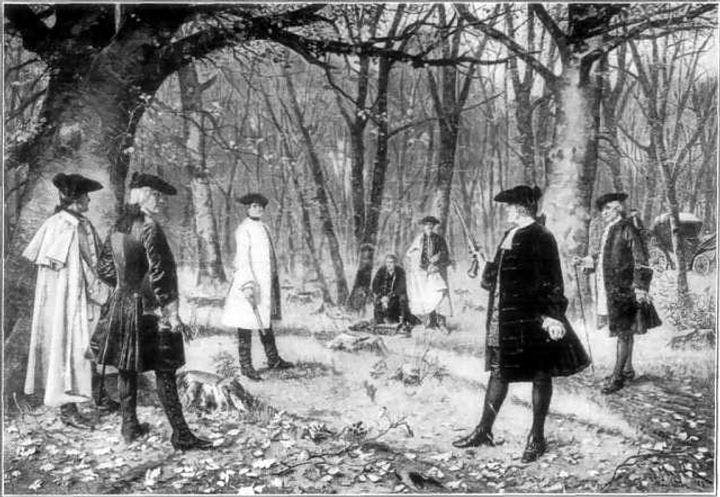

To take the special pleading first, flip to the event for which Burr (1756–1836) is best remembered. On the morning of July 11, 1804, Burr and former Treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton exchanged gunfire in Weehawken, New Jersey. Burr had challenged Hamilton to a duel in response to defamatory remarks by Hamilton that a third party passed on to a newspaper, and had refused to settle for Hamilton’s half-apologies. Hamilton missed by a mile; Burr did not miss.

Isenberg says that Hamilton may have fired first (most historians say otherwise), that he meant to discharge his weapon, and that to the very end he was minding his reputation (he converted to Episcopalianism on his deathbed and was eulogized as a religious man). That Hamilton had made a show of adjusting his pistol and donning his spectacles before the duel Isenberg trots out as evidence to rebuff "modern historians who see Burr as the aggressor."

But those historians have a good point. Burr was angry at Hamilton for working to deprive him of the presidency. In the election of 1800, Burr received the same number of Electoral College votes as his running mate, Thomas Jefferson, and it fell to the House of Representatives to sort out the mess. (The hastily ratified Twelfth Amendment ensured that this would never happen again.) In part due to Hamilton’s lobbying efforts, Jefferson became president. When Jefferson dropped Burr from the ticket for his 1804 reelection campaign, Burr ran unsuccessfully for governor of New York, with Hamilton again working against him behind the scenes. Burr’s resentment ran deep.

After Hamilton’s death, Burr escaped trial for murder and served out the remainder of his vice-presidential term. He presided over the impeachment proceedings against Supreme Court justice Samuel Chase with distinction, and delivered a farewell address to the Senate so touching that there was "a solemn and silent weeping for perhaps five minutes" after he finished.

Burr then moved west to establish a settlement in the Louisiana Territory whose inhabitants would double as a private army. War between America and Spain appeared likely; Burr and his men would invade and conquer Mexico so that it could be annexed to the United States. But political opponents feared that instead he wanted to found his own breakaway empire. He was soon arrested and put on trial for treason.

Isenberg’s determination to vindicate Burr pays dividends in the courtroom drama. She puts readers in the jury box and walks them through the twists and turns of the legal battles. The government did an awful job of making its case, and Burr’s team calmly but forcefully tore it apart. Reasonable doubt? Of course.

However, in passages about the trial and Burr’s post-acquittal exile in Europe, where he moved to escape creditors and political adversaries, alert readers will get the sense that he was up to something more. Burr did speak of western secession, at least in general terms. And while in Paris, he asked Napoleon to give him a few frigates to challenge the Spanish in North America—using Florida as his base of operations.

Does that make him a traitor? No. But it does raise old suspicions anew, and that’s not all to the bad. Isenberg, for all her attention to the public’s perceptions of Burr, doesn't seem to get that his villainy is the chief reason we find him so fascinating.

* * *

Reviewed: "Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr" by Nancy Isenberg, Viking, 2007.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons