As social mobility fades, so does meritocracy

– Molly Banta

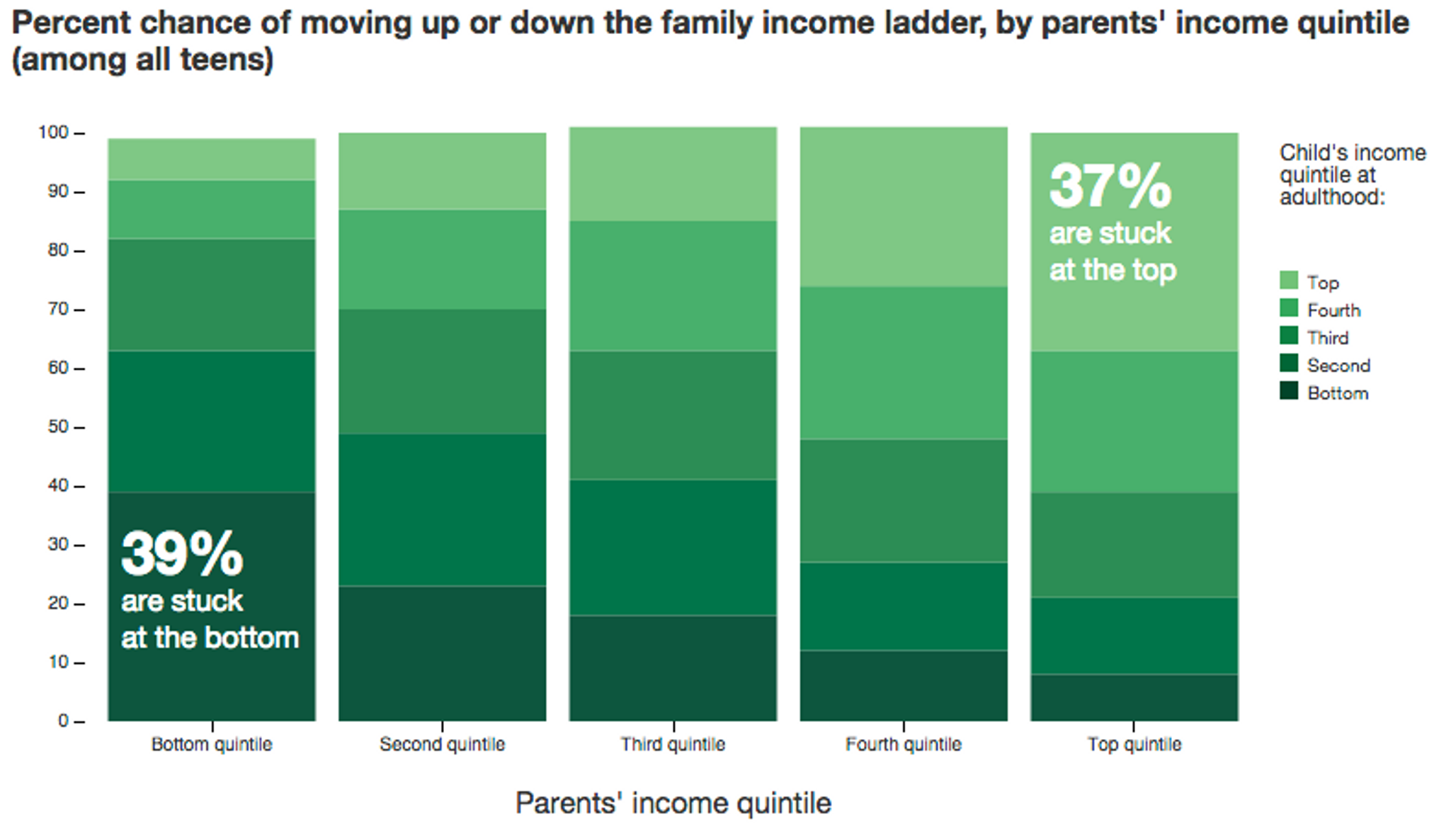

Just as poverty is understood to be cyclical or have a “sticky floor,” membership in the wealthiest class self-perpetuates, regardless of merit (or lack thereof).

The goal is instantly familiar to any parent (and most children): the hope that one day, your kids will be able to make a better life for themselves than the one you were able to live, and, in turn, that they will provide greater opportunities for generations yet to come.

On the broad socioeconomic scale, there are two ways to judge success in comparison to your parents: “Absolute mobility” measures whether or not the child is wealthier than their parents at the same age; “Relative mobility” is more complicated, measuring where the child ranks on the socioeconomic class scale, again compared to their parents at the same age.

For much of the 20th century, relative mobility was not regarded as all that important. With the GDPs of developed countries consistently expanding and their populations enjoying rising standards of living across generations, simply making more than your parents was all it took to achieve greater success than them.

The definition is less clear today. The number of high-level jobs (i.e. those that pay well and/or are in positions of power) and the frequency and attainability of higher education are no longer increasing as quickly from one generation to the next, and today’s economic crises, from student loans to stock market bubbles, prevent the same rapid growth in standard of living. Upward relative mobility is now more desired than ever, and yet by the very nature of basic fractions, the top fifth of society cannot expand to accommodate more; not even the talented can move up without someone from the upper class simultaneously moving down. Just as poverty is understood to be cyclical or have a “sticky floor,” membership in the upper class self-perpetuates, keeping even those unmerited at the top.

“Opportunity hoarding” becomes an issue when the achievement gap moves beyond matters of homework help and parental attention into the arena of institutional bias.

To study this phenomenon, Abigail McKnight, a senior research fellow at the London School of Economics, worked with a team to examined the social mobility of approximately 17,000 children born in the UK during the same week in 1970. Subjects’ initial cognitive scores were taken at age five, and the most recent follow-up conducted at age 42. The study unambiguously showed high-scoring five-year-olds should make for adults with high-earning or “top” jobs.

Troublingly, students’ cognitive scores skewed higher if they had wealthy parents: 37 percent of five-year-olds from the most-advantaged social class qualified as “high-skilled,” compared to just 8 percent of those from relatively disadvantaged families. The inverse was also true: 6 percent of those from advantaged backgrounds qualified as “low-skill,” while 35.8 percent of the disadvantaged fell into this category.

McKnight’s findings are unsurprising, though sobering. Among the children who scored low at age five in McKnight’s study, those from a more disadvantaged socioeconomic class were significantly less likely to be high-earners as adults, compared to low-scorers whose parents had higher income or higher educational attainment. Low-scoring children of parents with an upper-level degree had a substantially higher likelihood of making it into the top income bracket as adults when researchers controlled for differences in varying quality of British private and public education.

Differences can derive from natural potential and parenting from birth to age five (and onward). But there are profound socioeconomic influences on (and limits to) parenting. As Brookings expert Richard Reeves writes, “If a parent works hard to help their infant become more skilled, this is unambiguously fantastic news. The fact that more affluent parents are more willing or able to do so simply means we have to work harder to help ensure poorer kids do not fall behind. Otherwise the parenting gap becomes an opportunity gap.” Opportunity hoarding becomes an issue when the gap moves past simple help and attention and become institutionally skewed (via privileged access to education, connections or other means) towards the rich and powerful.

Talented but underprivileged kids are met with fewer opportunities to translate their high potential into tangible career success. The high probability of the wealthiest, low-scoring children to stay the wealthiest contributes to less room at the top for those who are underprivileged-but-talented to succeed.

And yet, for a society ideally based off competitive merit, success is unnaturally skewed towards the already rich and powerful, not the talented. Success may occur when a little natural ability and preparation meet a little luck and opportunity, but when luck and opportunity are inherited institutional privileges, the importance of natural ability and preparation fades away.

* * *

Further reading:

Abigail McKnight, “Downward Mobility, Opportunity Hoarding and the ‘Glass Floor,’” UK Social Mobility & Child Poverty Commission, June 2015.

Richard Reeves, “The Glass-Floor Problem,” New York Times, September 29, 2013. Accessed July 16, 2015.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock