The Behavioral Economist's Case for Prison Gangs

– Shannon Mizzi

Prison gangs play a vital role in the prison economy, in enforcing order, andd — counterintuitively — in reducing violence.

It may seem counterintuitive that gangs can exist in what is perhaps the ultimate tightly regulated environment. Gangs, however, have been thriving in American prisons since the 1950s, and are now ubiquitous. Why is it that the corrections system has been unable to eradicate gang activity from the facilities they run?

A recent article in Behavioral Economics by M. Garrett Roth and David Skarbek makes the case that gangs have actually become necessary elements within the prison system, allowing inmates to create and sustain an internal economy centered on contraband, eliminating much of the violence and disorder that would be present without them.

Through their examination of the California state prison system — the birthplace of the country’s most notorious prison gangs, including the Mexican Mafia, Nuestra Familia, and the Aryan Brotherhood — Skarbek and Roth discovered that correctional officers and prison authorities actually benefit from the existence of prison gangs, and have come to rely on gang hierarchies to maintain order, saving money in the process.

Skarbek and Roth cite statistics showing that while “the number of prison gangs and members has increased, prison violence has declined dramatically. The rate of inmate homicides declined 94% between 1973 and 2003 … [and] prison gang members are no more likely to engage in violent misconduct behind bars than non-gang inmates.” Gangs create powerful communities with influential leaders controlling member behavior. This allows for successful and controlled trade interactions between gangs, and actually prevents large-scale conflict by intimidating inmates who'd otherwise be likely to engage in violent behavior, thereby preventing disruptions of business activity.

Prison authorities acknowledge that it is impossible to eliminate all forms of prison contraband, especially in-demand items like alcohol, narcotics, and cell phones. In California, note the authors, 15,000 phones were seized from inmates in 2011 alone, and it is likely that many more went undetected. “During 11 days at one prison, officials used a device to detect more than 25,000 unauthorized calls, texts, and internet requests. Officials at the maximum-security prison at Corcoran even confiscated two cell phones from Charles Manson,” Skarbek and Roth write. “Contraband markets are working.”

Prison gangs prevent the contraband economy from becoming chaotic and inefficient, conditions that encourage violence. As there are no enforcement mechanisms to ensure trade is conducted fairly, inmates simply create their own. According to prison officials’ reports, inmates “cannot rely on correctional officers to enforce agreements made in drug deals, punish people who do not pay their drug debts, or knowingly protect a drug stash. For these illicit markets to operate, they must create extralegal governance institutions.” This is especially important as inmates are forced to interact with one another constantly, often for years at a time.

By creating what the authors term a “community responsibility system,” gang members streamline a prison’s internal economy, building relationships between gangs and making trade more efficient. Prison gangs typically have an established, hierarchical structure allowing for enforcement of rules regarding trade and gang interactions. They also have an interest in recruiting new inmates; the more unaffiliated inmates there are, the less efficient the community responsibility system becomes. In fact, Skarbek and Roth found that new inmates are actually encouraged to affiliate themselves with a gang by correctional officers for their own protection.

New inmates with a strong interest in obtaining contraband materials — drug addicts, for example — are particularly well-served by gang membership. There is no reason for a fellow inmate to trust that an unaffiliated individual will pay for goods sold to them. However, gang membership provides a guarantee that payment will be received, because prison gangs do business based on community responsibility. If a gang member buys something on credit from a rival gang, the purchaser’s entire gang is responsible for payment of the debt — and the seller’s gang can go to the leadership of the buyer’s gang to appeal for payment (whether it comes in financial form, or in violent retribution). This system of trust allows groups to continue to do business with one another, even if one member of either group turns out to be untrustworthy.

Skarbek and Roth write that aside from resolving trade disputes in a more orderly fashion, gangs help to prevent riots and “allocate scarce prison resources, such as benches and basketball courts, in the face of a shortage of such amenities.” This is why “the optimal number of prison gangs from the perspective of the warden is not zero.” If there are too many, of course, the prison must spend more to quell the resulting conflicts within and between gangs. If there are too few and the existing gangs are too large, the prison must use resources to encourage their breakup into smaller factions. In this way, prison wardens can “diffuse gang influence by maintaining the oligopolistic structure, which limits contraband but allows for orderly private allocation of prison-provided goods and dispute resolution.”

Similarly, there is an optimal gang size for both wardens and gang leaders. For gang leaders, higher membership means an increased diversity of skills, and allows for a more sophisticated organizational structure — and more power over limited resources. But when membership becomes too large, there is generally an increase in internal conflict, signifying that the organization has reached a point of diminishing returns. Interestingly, when gangs grow too large to remain cohesive, they often split based on secondary characteristics, such as what part of the state they are from: “In California, for example, the existence of a single Hispanic gang within many prisons would be untenably large. Consequently, geography is employed as a secondary criterion. … Hispanic inmates sort into gangs based on whether they come from north California, southern California, or the Fresno area.”

Is the prison system held hostage by gangs? Skarbek and Roth suggest a broader view. “Riots and other displays of public violence are less frequent when gangs exist,” and the trading of contraband material is never going to be wiped out completely, particularly with current resource levels. Authorities, perhaps, can take advantage of the structured nature of gangs to keep prisons somewhat safer than they would be without them.

* * *

The Source: “Prisons Gangs and the Community Responsibility System” by M. Garret Roth and David Skarbek, Review of Behavioral Economics, 2014.

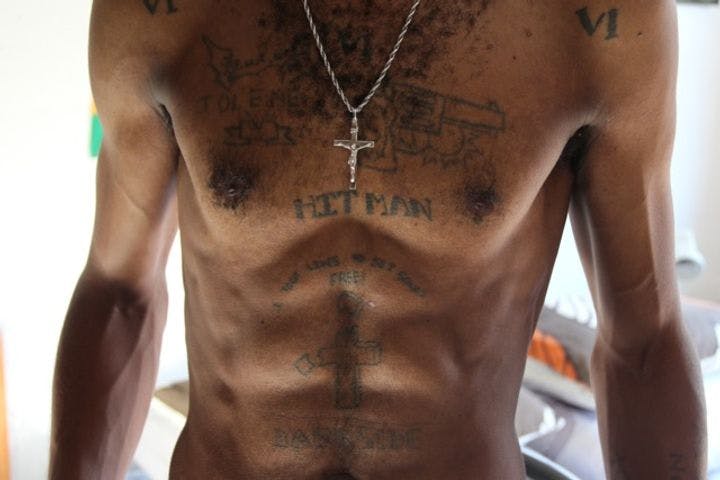

Photo courtesy of DFID