Summer 2011

Beyond the Bully Pulpit

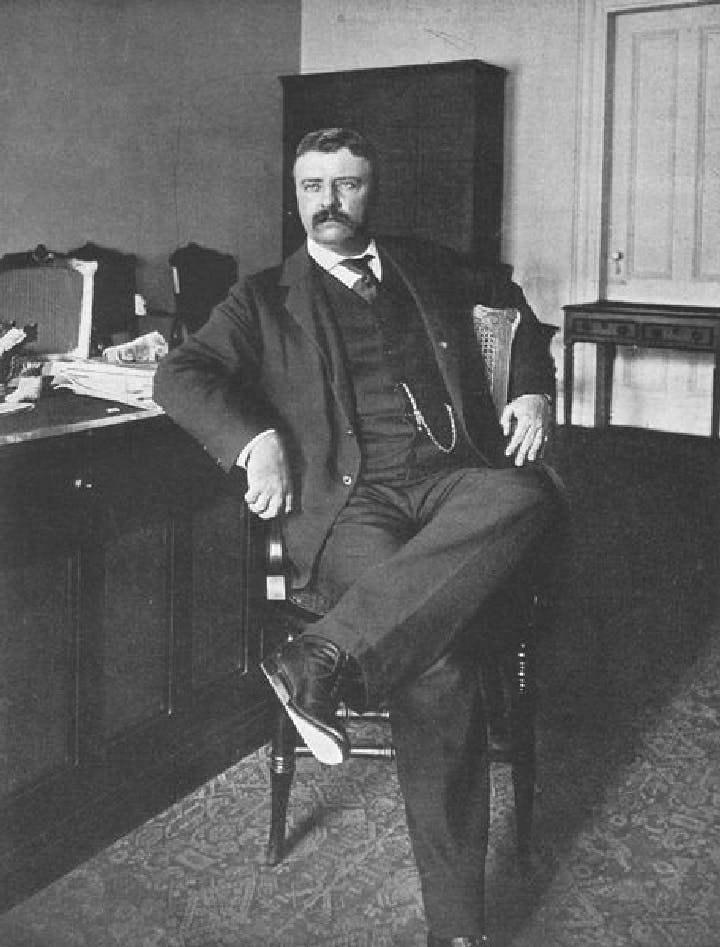

– David Greenberg

Theodore Roosevelt famously used the “bully pulpit” of the White House to advance his agenda. By the time he left office, “spin” had become a fundamental part of the American presidency.

When President William McKinley led the United States to war against Spain in the spring of 1898, no one was keener to see battle than Theodore Roosevelt. Scion of an upper-crust New York City family and a Harvard graduate, the ambitious, brash assistant Navy secretary had, at 39, already built a reputation for reformist zeal as a New York state assemblyman and as Gotham’s police commissioner. Lately, from his perch in the Navy Department, he had been planning—and agitating—for an all-out confrontation with the dying Spanish Empire. In his official role, he drew up schemes for deploying the U.S. fleet, which he had done much to strengthen. Privately, he mocked the president he served, who, to the exasperation of TR and his fellow war hawks, had been temporizing about military action. “McKinley has no more backbone than a chocolate éclair,” Roosevelt told his friend Henry Cabot Lodge, then the junior Republican senator from Massachusetts.

McKinley soon bowed to political pressure and opted for war. Most Americans applauded. Roosevelt resolved not to validate the sneers that he was just playing at combat. “My power for good, whatever it may be, would be gone if I didn’t try to live up to the doctrines I have tried to preach,” he declared to a friend. Newspaper editorialists demanded that he remain at the Navy Department, where they said his expertise was needed, but Roosevelt quit his desk job, secured a commission as a lieutenant colonel, and set up a training ground in San Antonio, Texas. Along with his friend Leonard Wood, an Army officer and the president’s chief surgeon, he readied for battle an assortment of volunteer cavalrymen that ranged from Ivy League footballers and world-class polo players to western cowboys and roughnecks. The New York Sun’s Richard Oulahan dubbed the motley regiment the “Rough Riders.” Others called them “Teddy’s Terrors,” even though Wood, not Roosevelt, was the unit’s commander.

As competitive as he was patriotic, Roosevelt meant for his men to vanquish the Spanish in Cuba. But he also wanted the Rough Riders to seize the imagination of Americans at home. While still at camp in Texas, TR wrote to Robert Bridges, the editor of Scribner’s magazine, offering him the “first chance” to publish six installments of a (planned) first-person account of his (planned) war exploits—a preview of what would be a full-blown book and, in Roosevelt’s assessment, a “permanent historical work.” Bridges accepted. (Published the following year, The Rough Riders was an immediate bestseller.) Once TR set off for Cuba, he made sure his favorite reporters would be joining him. And though the vessel that shoved off from Tampa, Florida, was too small to accommodate all of the Rough Riders comfortably, TR insisted that they make room for a passel of journalists. According to one oft-told account, Roosevelt even escorted onboard two motion-picture cameramen from Thomas Edison’s company. Though likely apocryphal, the story captures Roosevelt’s unerring instinct for publicity, which was entirely real.

The conflict in Cuba, dubbed the “Correspondents’ War” for the feverish journalistic interest it provoked, had been grist for the papers ever since the Cuban insurrection against the Spaniards’ repressive rule began in 1895. Playing on—and playing up—the widespread American sympathy for the Cubans, the mass-circulation newspapers and magazines, led by William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, covered the rebellion avidly. Western Union telegraph cables connecting Havana with Key West—and hence the whole of the United States—gave Americans news of the battles with unprecedented speed.

To the journalistic entourage accompanying the American soldiers, the charismatic Roosevelt was an obvious draw. His reporter companions lavishly recorded instances of his courage, which by all accounts was genuine. The celebrated reporter Richard Harding Davis, a starry-eyed admirer, described Roosevelt speeding into combat at the Battle of San Juan Hill with “a blue polka-dot handkerchief” around his sombrero—“without doubt the most conspicuous figure in the charge. . . . Mounted high on horseback, and charging the rifle-pits at a gallop and quite alone, Roosevelt made you feel that you would like to cheer.” Newsreels also seared Roosevelt’s stride into the public mind as audiences lapped up shorts starring the Rough Riders. According to The World, the young lieutenant colonel had become “more talked about than any man in the country.”

Within weeks, this “splendid little war,” as Secretary of State John Hay described it to TR, was over. That fall, captivated by the hype of his heroism, New York voters elected Roosevelt their governor. Two years later, McKinley, seeking reelection, chose TR as his new running mate; surprising no one, they won handily. Then, in September 1901, a gunman took McKinley’s life, and the American presidency had, in this 42-year-old gamecock, its first full-fledged celebrity.

More than any other U.S. president, Theodore Roosevelt permanently transformed the position of chief executive into “the vital place of action in the system,” as his contemporary Woodrow Wilson put it. What had been largely an administrative position, subordinate in many ways to Congress, grew into the locus of policymaking and the office everyone looked to for leadership on issues large and small. Roosevelt benefited, of course, from timing: He took office as a new century dawned, when social and economic injustices were crying out for redress from Washington and America was assuming a leading role on the world stage. No longer could presidents dissolve into obscurity like the “lost” chief executives of the Gilded Age, of whom Thomas Wolfe cruelly asked, “Which had the whiskers, which the burnsides: Which was which?”

For Roosevelt, fashioning a popular image was not an ego trip but an aspect of modern presidential leadership.

Unlike most of his predecessors, TR grasped that effective presidential leadership required shaping public opinion. This insight was not wholly novel. For example, Abraham Lincoln, in his debates with Stephen Douglas in 1858, said, “Public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed.” But the boldness of Lincoln’s wartime leadership as commander in chief obscures the fact that he was not a legislative leader. Besides, Lincoln’s embrace of executive power in the name of the public was unusual for 19th-century presidents, most of whom accepted the firm constitutional limits on their capacities, rarely even delivering speeches that amounted to more than ceremonial statements. Roosevelt, in contrast, spoke to the public often, usually with high-flying confidence and an unconcealed point of view. It was significant, too, that by Roosevelt’s day public opinion no longer meant, as it once had, the view of “the class which wears black coats and lives in good houses,” as the British political scientist James Bryce wrote; it now signified the mass opinion of a surging, diverse, and increasingly interconnected populace. Appreciating this change, Roosevelt sought to shape the way issues and events were presented to the clamorous hordes in whom political power increasingly resided.

To do so, Roosevelt capitalized on changes in journalism and communications. The old partisan press was giving way to a more objective, independent journalism that valued reporting, and TR realized the advantage in making news. He took the bold step of traveling the country to push legislation and otherwise used what he called the “bully pulpit” to seize the public imagination. Perhaps most important, he cultivated the Washington press corps as none of his predecessors had. The presidential practice of using the mass media to mold public opinion—what today we call spin—was in its embryonic state, and no one did more to midwife it into being than Theodore Roosevelt.

With his zest for the spotlight, Roosevelt was as well equipped as any occupant of the office to carry out this transformation. “One cannot think of him except as part of the public scene, performing on the public stage,” wrote the philosopher John Dewey, who was Roosevelt’s junior by one year and an unlikely enthusiast. Many Americans, to be sure, found it hard to stomach Roosevelt’s antics and his preternatural confidence in himself. Mark Twain saw TR as one of his own parodic creations come to life—a juvenile, showboating ham, “the Tom Sawyer of the political world of the 20th century; always showing off; . . . he would go to Halifax for half a chance to show off and he would go to hell for a whole one.”

To defenders such as Dewey, though, such carping was misdirected, for Roosevelt was merely succeeding on the terms of his age. “To criticize Roosevelt for love of the camera and the headline is childish,” the philosopher wrote, “unless we recognize that in such criticism we are condemning the very conditions of any public success during this period.” Dewey tolerated Roosevelt’s grandstanding, which he noted was a prerequisite for political achievement in the 20th century, particularly for those seeking to impose significant change. As journalist Henry Stoddard explained, the power of the Gilded Age conservatives was so entrenched that it would have been futile for Roosevelt to use the methods “of soft stepping and whispered persuasion” to try to implement his reformist vision.

More than a strategy for governing, Roosevelt’s dedication to publicity thoroughly informed his conception of the presidency—a conception that was as bold, novel, and purposeful as Roosevelt himself. Rejecting the view of the executive as chiefly an administrative official, TR considered the president the engine and leader of social change—and fused this idea to that of an activist, reformist state. Over the previous half-century, the unchecked growth of industrial capitalism had raised the critical question of whether government could be enlisted to preserve a modicum of economic opportunity and fairness in society. Roosevelt thought it could, and he equated the drive to reform the rules of economic life—to use state power to counter the trusts—not with radicalism or socialism, but with responsible governance in the name of the whole nation. In The Promise of American Life (1905), Herbert Croly, the theorist of progressivism, called Roosevelt “the first political leader of the American people to identify the national principle with an ideal of reform.”

Mark Twain grumbled that TR “would go to Halifax for half a chance to show off” and “to hell for a whole one.”

The national principle that Roosevelt believed in transcended factional concerns. Unlike most of his predecessors, Roosevelt saw himself as an instrument not of the party that elected him or of a coalition of blocs, but of the will of the people at large. Deriving his power from the general public, however, did not mean slavishly following mass sentiment; TR, like Wilson after him, wanted to discern with his own judgment which policies would truly serve the electorate as a whole. “I do not represent public opinion,” he wrote to the journalist Ray Stannard Baker. “I represent the public. There is a wide difference between the two, between the real interests of the public and the public’s opinion of these interests.” He spoke of the common good as if such a unitary thing were not hard to identify, at least for him.

To the project of galvanizing public opinion, TR brought the boundless force of his personality, channeling it into a moral message. Later generations of liberals, starting with the New Deal, disdained the moralism of progressives in favor of pragmatic political problem-solving. But TR, the quintessential progressive, saw political questions as spiritual ones: His advocacy of social improvement was high-minded and hortatory. In his speeches he denounced greedy corporations, excoriated corruption, implored his audiences to improve their character, and called for a restoration of the manly virtues he held dear. To be sure, the moralism that served as a wellspring of reform also produced a misguided—and to a later era’s sensibility, hopelessly retrograde—faith in the superiority of his own race, class, and sex to assume the burdens of leadership. (He justified both the conquest of the West and the United States’ acquisition of imperial holdings in the Pacific in nakedly racial terms.) Impatient with the faint of heart, he mistook ambivalence for weakness. “I don’t care how honest a man is,” he asserted. “If he is timid he is no good.” But if his zeal could yield a misplaced righteousness, and if his restlessness blinded him to the virtues of slow reflection, he did correctly see that rousing America at a critical juncture in the nation’s economic history demanded a raucous, relentless, and even messianic rhetoric, aimed at the democratic masses.

The activism inherent in Roosevelt’s theory of the presidency has been often noted. Less remarked upon is how the idea also bade him to think broadly about the public. Roosevelt believed that the president should be the duty-bound agent of the American people; but, equally important, he was also the repository for their hopes and fears. Again, publicity counted: The people’s interest in the president as a personality allowed him to dramatize himself, to take advantage of his role not just as a programmatic leader but as a symbol of the nation. “It is doubtful if any power he has over us through his office or through his leadership of a party is so great as this which he exercises directly through his example and character,” wrote William Garrott Brown, a Harvard historian.

TR was acutely conscious of this symbolic role. After one tour of the West, he wrote about his interactions with those who had come to hear him. His remarks, at first glance condescending, actually reflected a keen appreciation of why the presidency mattered. “Most of these people habitually led rather gray lives,” he wrote of his crowds. “And they came in to see the president much as they would have come in to see the circus. It was something to talk over and remember and tell their children about. But I think that besides the mere curiosity there was a good feeling behind it all, a feeling that the president was their man and symbolized their government, and that they had a proprietary interest in him and wished to see him and that they hoped he embodied their aspirations and their best thought.” The president’s persona was not a distraction from substantive policy; nor was it a superficial veneer that concealed a different, more authentic inner self. Rather, it was an expression and focal point of public sentiment, a source of inspiration and connection to the democracy. Fashioning a popular image, accordingly, was not an ego trip, or a detour from governing, but an aspect of modern presidential leadership.

By the time he became president, Roosevelt had been practicing the art of publicity for so long that it was second nature. As soon as he entered politics, at age 23, he cultivated reporters, whose company he manifestly enjoyed. In the 1890s, as New York City police commissioner, he conscripted reform-minded reporters Jacob Riis and Lincoln Steffens to guide him through the urban demimonde of cops and criminals; in return, he burnished their reputations and helped them publish their work. In New York’s statehouse, Roosevelt had initiated twice-daily sessions with the Albany correspondents, serving up a rapid-fire stream of tidbits, judgments, and jokes.

His ascension to the presidency meant that even more of his life would be on view. Without planning to, he placed his family in the media’s crosshairs. From Alice, his daughter from his first marriage, who at 17 burst upon the Georgetown social scene, to the three-year-old Quentin, the six exuberant Roosevelt offspring proved irresistible to society page editors. Roosevelt initially opposed the attention and never stopped complaining, but he also had to see that more ink for the president was an unintended side effect and benefit.

Roosevelt surrendered another bastion of presidential privacy by turning family retreats into working vacations. When McKinley had escaped Washington’s fishbowl with visits to his native Canton, Ohio, reporters seldom followed. But in 1902, after the Roosevelts launched a renovation of the Executive Mansion and repaired to his Sagamore Hill estate in Oyster Bay, Long Island, TR announced that he would be conducting official business all the while—in one stroke, a reporter noted, “transfer[ring] the capital of the nation to this village by the sound.” A horde of correspondents tagged along. When the reporters filled the news lulls with gossipy accounts of the first family’s antics, the president protested, oblivious to his own role in having whetted the appetite for presidential news. Presidential vacations were never the same again.

If TR drew notice when he didn’t seek it, far more numerous were the times when he pursued it actively—and strategically. To be sure, Roosevelt was building on a foundation laid by others. McKinley, for example, had made the first campaign film, shown in theaters just months after Thomas Edison’s original projectors were up and running—a rudimentary newsreel of the candidate pacing around his Ohio homestead that, despite its simplicity, sent audiences into frenzied reactions. In his first days in the White House, McKinley hosted an East Room reception for reporters that won him lasting favor. Most important, he allowed the self-effacing George Cortelyou, the White House secretary—a chief of staff and aide-de-camp rolled into one—to begin to organize the handling of press requests for information, which spiked during the Spanish-American War. For the first time, the president had a formal system for dealing with inquiries from White House correspondents, whose ranks were growing every year.

Presidents who have mastered the machinery of spin have merely succeeded on the terms of their own age.

Wisely retaining Cortelyou, who would become his unsung partner in many of his ventures, Roosevelt expanded the White House press operation significantly. Some of TR’s methods would become staples in the presidential bag of tricks. He discovered that releasing bad news on Friday afternoons could bury it in the little-read Saturday papers, while offering good news on torpid Sundays could capture Monday’s headlines. He leaked information to reporters, sometimes floating “trial balloons,” by whispering to select reporters, under the protection of anonymity, of possible future plans; the reporters would then gauge the fallout without the presidenthaving to declare his course publicly. TR also monitored the presence—or absence—of cameras at events. He once delayed signing a banal Thanksgiving Day proclamation until the Associated Press photographer arrived; without a picture, such a story would be far less likely to make the front page.

Antagonists were quite correct in identifying Roosevelt’s sweeping efforts to promote his agenda and himself—efforts that understandably offended the guardians of the old order. One vocal detractor, “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, a six-foot-tall Democratic senator from South Carolina known for once threatening to spear President Glover Cleveland with a farm tool, complained, “Theodore Roosevelt owes more to newspapers than any man of his time, or possibly of any other time.” But Tillman and his kind were mistaken in deeming the president’s public support illegitimate; enthusiasm for such initiatives as railroad-rate regulation, pure food and drugs, and antitrust actions was widespread, as was admiration for these policies’ full-throated champion in the White House. What TR understood that Tillman did not was that in the new landscape of mass media, a president’s campaign for publicity—whether fueled by ego or not—constituted a key part of presidential leadership, an indispensable means to an end.

This was a crucial insight of Roosevelt’s, and understanding it as more than self-justification requires reconciling the two seemingly contradictory meanings of the word publicity in early-20th-century America, both of which meant “making something public.” Originally, the word’s chief connotation wasn’t the self-aggrandizing pursuit of attention, though that usage was becoming more common. Rather, it meant a commitment to laying bare the facts, something like transparency or sunlight. It signified an objective—not subjective—presentation of previously secluded facts. As overtly partisan journalism fell into disfavor, reporters—like their counterparts in a host of new academic social sciences—placed increasing weight on the discovery of data and evidence. Even the so-called muckrakers, remembered for their political activism, stressed the disclosure of information as the key to effecting reform. Likewise, progressive politicians such as Roosevelt believed that if the wrongdoing of backroom politics or corporate malfeasance were exposed to the light of day, the ensuing popular outcry would force the powerful to change their ways. When a journalist at The New York World wrote that TR’s strategy as police commissioner was “Publicity! Publicity! Publicity!” it wasn’t simply to mock his love of the headlines; it meant that he was laying open his department’s workings for public consideration. As president, Roosevelt often called for publicity as a mechanism for checking the rapacity of the trusts. “The first essential in determining how to deal with the great industrial combinations,” he said in his initial presidential message to Congress in 1901, “is knowledge of the facts—publicity.”

Within a few years, the emergence of public-relations professionals in business (and soon thereafter in government) would set these two meanings of publicity in seeming conflict. The hired professionals would gain a reputation for spinning information to put the best face on it, or opportunistically promoting events that lacked intrinsic news value; in so doing, they transformed publicity from a synonym for full disclosure into something like an antonym—a term for selective, self-serving disclosure. For Roosevelt, however, the meanings were never fully distinct, and what his critics might see as the latter practice he justified under the virtuous aura of the former.

Theodore Roosevelt was not alone in developing the machinery of spin that would come to be an indispensable part of the presidency. Not only had his predecessors taken baby steps toward creating mechanisms for influencing public opinion, but several of his contemporaries—most notably Woodrow Wilson—did arguably just as much to direct presidential energies toward the general citizenry. And Wilson would also do much as president to enlarge the office. Both men sought to simplify things for public consumption, but where TR liked to dramatize, Wilson aimed to distill. If Roosevelt belittled Wilson’s “academic manner . . . that of the college professor lecturing his class,” Wilson scorned his predecessor’s theatrics—even looking askance at the popular use of the nickname “Teddy” as a sign of the unfortunate return of the “old spirit of Andrew Jackson’s time over again, the feeling of disrespect and desire to make everything common property.”

U.S. political culture retains more than a touch of the Wilsonian disdain for personalities in politics. Americans regularly hear—and tend to endorse—the notion that for politicians to trade on image and style, or for the news media to dwell on such things, is to divert public attention from more pressing business. Every successful president has suffered imputations that he has in sinister fashion charmed the press or used a new medium of communication (radio, television, the Internet) to claim an undeserved standing. But the insights of John Dewey, an apologist for neither public-relations agents nor sensationalist journalism, bear recalling. Presidents who have mastered the machinery of spin, from TR’s cousin Franklin to Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama, have merely succeeded on the terms of their own age. If not all of them have shared Roosevelt’s taste for grandstanding, they have consciously or intuitively appreciated how his talent for self-dramatization helped him gain the attention and favor of reporters and voters.

Today, presidents have no choice but to constantly tend their images and refine their messages to sustain public support for themselves and their agendas. From Teddy’s rudimentary if nonetheless groundbreaking system of White House press management has evolved a vast apparatus of spin—an apparatus that has come to include press secretaries, advertising professionals, public-relations gurus, speechwriters, pollsters, image consultants, media mavens, and now Web masters, social media directors, and videographers.

Americans may resent the powerful influence these people exert over the words and images the president directs their way, and it’s understandable that they might wish to see the number of these message shapers reduced. But at the same time, just as TR required new techniques to promote the progressive reforms he sought, so did his successors. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine how, without the vast machinery of presidential spin that has developed in the last century, any political change of consequence could ever be achieved.

* * *

David Greenberg, currently a Woodrow Wilson Center fellow, is a professor of history and of journalism and media studies at Rutgers University. The author of numerous books and articles about political history, both scholarly and popular, he is writing a history of U.S. presidents and spin.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons