Summer 2010

Chapter and Verse

– The Wilson Quarterly

A diminishing sense of literary style, poet Robert Alter writes, is depriving us of "one of the keen pleasure in the reading experience."

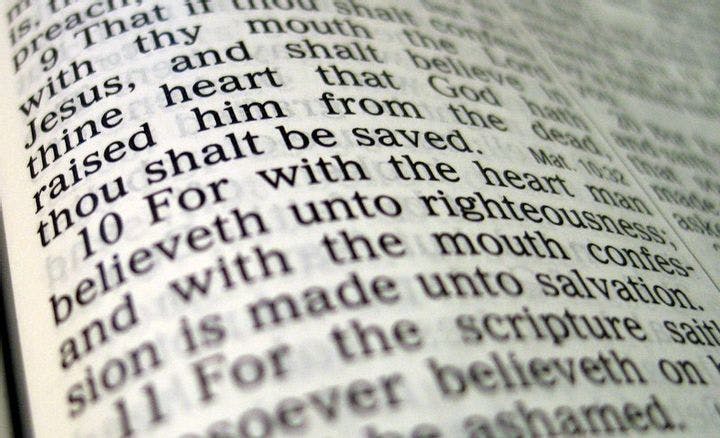

That the 1611 King James Bible once exerted a profound influence on American literature is as inarguable as observing, along with Robert Alter, that there has been a “general erosion of a sense of literary language.” He suggests no causal connection, simply noting that serious literature and a literary voice once honed by letter writing have given way to novels that are “flat and banal” and “the high-speed shortcut language of e-mail and text messaging.” Alter writes that we are losing “one of the keen pleasures in the reading experience.”

Consider one of the more exhilarating passages from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), in which the doomed Captain Ahab rails against savage nature but ultimately acknowledges his unbreakable connection to the sea: “Then hail, for ever hail, O sea, in whose eternal tossings the wild fowl finds his only rest. Born of earth, yet suckled by the sea; though hill and valley mothered me, ye billows are my foster-brothers.” Though Melville marshals other influences (there is more than a touch of King Lear in the passage’s sensibility, for instance), his rhythm and syntax—“born of earth, yet suckled by the sea,” “ye billows”—are borrowed from the formal language of the Bible.

A diminishing sense of literary style, poet Robert Alter writes, is depriving us of "one of the keen pleasure in the reading experience."

Another great 19th-century stylist, Abraham Lincoln, understood how using deliberately archaic flourishes such as “four score and seven years ago” could not just heighten oratory but lend what Alter calls “a strong note of biblical authority.” Although only one phrase in the Gettysburg Address is a direct quotation from the King James Bible—“shall not perish from the earth”—its inclusion lends Lincoln’s American English reach and resonance. In his second inaugural address, Lincoln speaks of how strange it may seem “that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we may be not judged.” Linking a reference to slavery to a modified quotation of Luke 6:37 (from the Beatitudes) that occurs just after Jesus’ injunction to “love your enemies” underscores for Alter how much the moral authority of the 1865 Lincoln speech was made possible by the language of the Bible. “At a cultural moment when the biblical text . . . was a constant presence in American life, the idioms and diction and syntax incised in collective memory through the King James translation became a wellspring of eloquence.”

Alter, who teaches Hebrew and comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley, identifies William Faulkner as the last major American writer to be strongly influenced by the King James Version, though more thematically than linguistically. In such novels as Absalom, Absalom! (1936) and The Sound and the Fury (1929), Faulkner’s biblical allusions not only provide signposts to the morality of key characters in fictional Yoknapatawpha County but also add allegorical weight to his contemporary dramas.

Has appreciation of the literary style of writers such as Faulkner or Melville vanished forever? Alter laments that “teachers of literature and their hapless students have tended to look right through style to the purported grounding of the text in one ideology or another.” They and others are missing the “deep pleasure” of the “play of style in fiction,” and the fine mental connections and discriminations it affords.

THE SOURCE: "American Literary Style and the Presence of the King James Bible," by Robert Alter, in New England Review, Vol. 30, No. 4 (2009-10).

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Paul L. McCord, Jr.

Up next in this issue