Every joke is a tiny revolution

– Molly Banta

Political comedy is used to persuade and bond likeminded groups together, while publicly ridiculing outsiders. That's true whether you're Jon Stewart or ISIS.

“That is the equivalent of needing a babysitter and hiring a dingo.” It’s not a slogan you’d expect to transform the debate on net neutrality in the United States and mobilize 45,000+ comments on the Federal Communications Commission’s website in support of open-access internet. But with a combination of side-splitting wit and a critical eye, John Oliver, host of HBO’s Last Week Tonight, flung the issue — whether or not internet providers should be able to offer high speeds for certain websites or types of content — into the spotlight. Net neutrality, he argued, may be the most boring words in the English language, but twist it into a joke about coyote urine, Usain Bolt on a motorbike, or dingoes eating children, and suddenly America cares.

The satirical political humor employed by Oliver and his progenitor, Jon Stewart — and mimicked, often less successfully, by millions of self-styled commentators online — is known to some academics as “political culture-jamming”: the author may manipulate a common idea to disrupt (or “jam” up the culture) and publicly call out its hypocrisy. Jokes in this vein demand serious understanding on the part of the comic, but require minimal background knowledge on the part of the audience, sparking interest and understanding of an issue in a way that a book or essay might not.

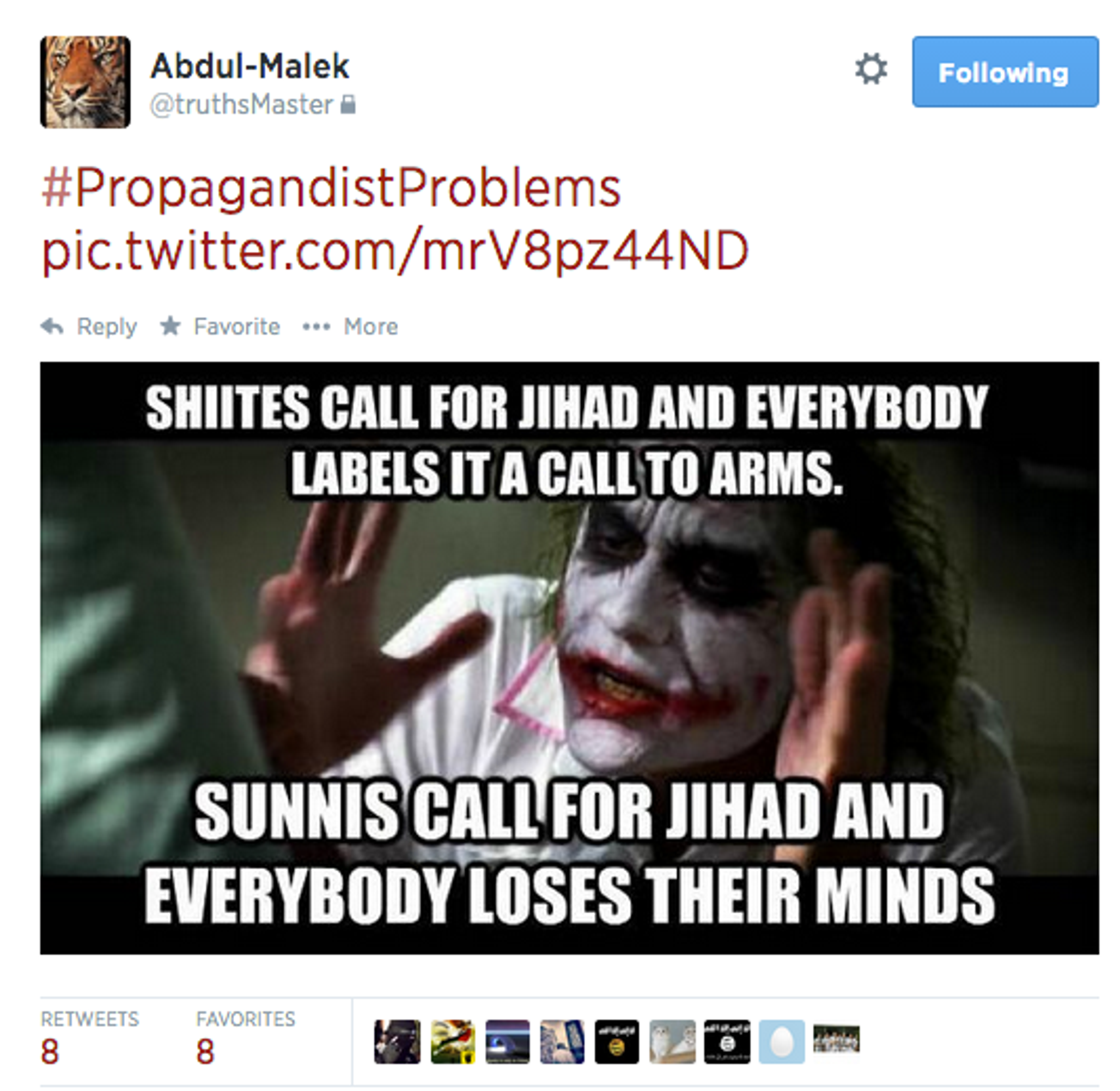

A somewhat more lowbrow online cousin to Oliver or Stewart’s humor can be found in the form of memes, the funny images, video, or text that spread rapidly as crowdsourced in-jokes across the web. The term itself was coined by biologist Richard Dawkins in 1976’s The Selfish Gene as a conceptual means to understand the way cultural information spreads. Online, memes are easily shared across the internet in a way that “blurs the lines between readership and authorship,” writes Laura Huey in the Journal of Terrorism Research. Sharing a meme on Facebook or Twitter — even without originating it — implicitly attributes enough credit to the individual that they feel cool and trendy among their peers.

“Culture jamming” is seen across all ideologies. While perhaps the most common form involves younger generations mocking the mainstream, conservative types have also employed this approach to poke fun at the more liberal or countercultural elements in society. Ultimately, political jams are made to persuade and bond any like-minded group together, while using wit to publicly ridicule the outsiders. Political jamming in the Western world is employed commonly in mainstream media, where satirical TV programs like The Daily Show are a primary news source for young people to understand current events. And this twenty-first century breed of news media actually affects public policy: John Oliver’s 13-minute “net neutrality” segment did just that.

But what happens when this highly effective method is employed by a terrorist or terrorist organization? As James Farwell explains in Persuasion and Power, “Despite the expertise and sophistication of political communications … in the West, al-Qaeda is beating us at our own game. ... They know how to forge, protect, and drive messages that strike a responsive chord.” And the Islamic State (ISIS) is even more effective, bridging cultural gaps across the internet, not only through the romanticism of violent Islam that Western media seems to highlight daily, but also through normalized satire and humor.

ISIS effectively uses social media as an interactive outlet where frustrated youth do not necessarily create the jokes themselves, but still reap the benefits of recognition from their peers in the hip subculture of “jihadi cool.” Thus, teens change unknowingly from reading passively to sympathizing more easily with the broader jihadist movement, particularly as these memes get shared and their niche, online echo chamber gives them credibility.

Censoring this critical satire, writes Huey, is not the answer. There is still a large gap between the angsty teen looking at darker memes and the Western jihadist-wannabe traveling to Syria to wage a violent war. Merely condemning this dissatisfied community or labelling potential young jihadis as ‘brainwashed’ will not effectively combat ISIS’s recruiting techniques; part of the “cool” of jihad counterculture is the edgy outsider status that comes with being ‘misunderstood’ by the West.

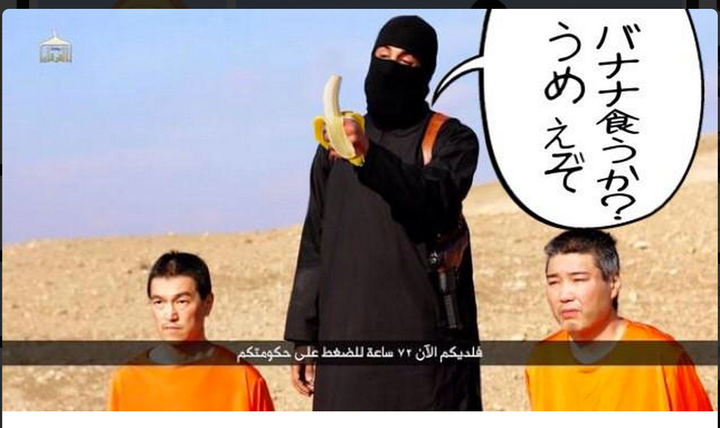

It is essential to specifically counter this perception of cool that has seduced so many young Muslims. The U.S. government must continue to highlight not only how evil, but uncool ISIS is. As many Japanese Twitter users did in response to the ISIS ransom demand video of hostages Kenji Goto Jogo and Haruna Yukawa, responding with humor, rather than fear, undermined the original intimidating goal of the video.

While some were upset with the light-heartedness of the memes, one commenter perfectly captured the necessary balance between mourning the hostages and mocking ISIS: “Tomorrow will be sad but it will pass and #ISIS will still be a big joke. You can’t break our spirit.” Another wrote, “You can kill some of us, but Japan is a peaceful and happy land, with fast Internet. So go to hell.” It is important to understand the shock and aversion to brutality ISIS wants us to feel – and then use comedy to destroy the glamor of their violence.

President Obama is active on social media, a senator from Connecticut recently used a shruggie emoji on the Senate floor, and the State Department dabbled with its first BuzzFeed post this year, but the U.S. government is still struggling to use the social media that some ISIS supporters use so adeptly.

There are, however, some encouraging notes. Peer 2 Peer: Challenging Extremism is the State Department’s new semester-long program where college students create a social media campaign to counter terrorist recruiting. Other students have aimed at reinforcing positive Muslim communities, creating apps like 52JUMAA, the digital platform ONE95, and a prevention campaign named WANT (as in “We Are Not Them”). At least for a moment, it seems that the online fight against extremism has been outsourced to the meme-armed experts: college students.

* * *

The Source: Laura Huey, “This is Not Your Mother’s Terrorism: Social Media, Online Radicalization and the Practice of Political Jamming,” Journal of Terrorism Research [Online] 6:2