Fall 2014

How “Seinfeld” and “The Simpsons” Changed TV Forever

– Gina Masullo

In 1989, "Seinfeld" and "The Simpsons" debuted. Yada, yada yada … television permanently changed.

JULY 1989 WAS A BUSY MONTH in the TV business. Networks cut frenetically from stories about the first suicide attack in Israel to pieces on the presidential elections in Iran to coverage of United Airlines Flight 232, which crashed in Iowa and left 112 dead. A month earlier, the Tiananmen Square protests were crushed by the Chinese government. Longstanding, oppressive institutions were being challenged or overthrown. The world was changing, and amid the swirl of revolution and upheaval, a different type of TV show premiered. It began with two average-looking men chatting in a well-lit but otherwise nondescript diner.

“That button’s in the worst possible spot,” says one, gesturing to the other’s outfit. “The second button literally makes or breaks the shirt. Look at it — it’s too high! It’s in no-man’s land. You look like you live with your mother.” The next 22 minutes scrutinized all matter of minutiae: cotton balls, different types of handshakes, and over-drying clothes at the laundromat.

For better or worse, popular culture serves as a generational signpost, telling us where society is heading as the future loses its haze and comes into view. Pop culture in 1989 was no different: the Nintendo Game Boy foretold a world of portable gaming on handheld devices; Milli Vanilli, with four of the year’s biggest hits (before their careers were derailed by the revelation that they couldn’t sing and were just lip-synching), signaled the bait-and-switch of over-produced, manufactured mainstream music stars; the first commercially-available dial-up internet connection was a small crack in the dam that released the flood wave of the Digital Age. The list goes on.

On network television (then the top source of daily entertainment for most Americans), viewers were introduced to new shows like “Baywatch,” “Saved by The Bell,” and “The California Raisin Show” (itself an example of the rise of product placement and content marketing). Sprinkled among the lighter fare, several innovative and even culture-shifting shows debuted. “Life Goes On” was the first major series to feature a main character with Down syndrome. Arsenio Hall became the first African-American to host his own major late-night talk show. Even “COPS” was a breakthrough — a “reality show” on the air three years before MTV’s “The Real World” debuted its motley cast of characters.

MORE THAN 130 SHOWS PREMIERED IN 1989, but two stood out from the rest, and went on to make a lasting cultural impact transcending the boundaries of television: “Seinfeld” and “The Simpsons.” Together, they upended the long-standing TV tropes of teachable moments, neatly wrapped-up conflicts, loving relationships, and careful political correctness. Sentimentality was out, and satire, self-awareness, and sarcasm were in.

“Seinfeld” co-creator Larry David famously commanded the show’s writing staff to follow a new mantra: “No hugging. No learning.” Just one year earlier, America’s most popular show on TV was “The Cosby Show,” all sugarspun togetherness, strong parenting, and wholesome American values. Once “The Simpsons” announced itself, FOX soon moved the show from its Sunday night timeslot to Thursday night — viewers’ final ‘TV night’ before the weekend, thus commanding major ad dollars and prompting networks to fill the evening with their most popular shows. On Thursday, “The Simpsons” would compete head-to-head against Cosby and the rest of NBC’s “Must See TV” juggernaut. By 1994, “Seinfeld” — which supplanted “Cosby” as the anchor of NBC’s Thursday night lineup — was tops.

Though different in their delivery and values (or lack thereof), “Seinfeld” and “The Simpsons” are linked by their intelligence, deft writing, focused boundary-pushing, fixation on meta-humor, and by their selfish, lazy, largely irredeemable main characters. Years before revered antiheroes like mafia boss Tony Soprano ushered in television’s so-called “golden age,” Homer Simpson smashed his son’s piggy bank in search of beer money, Jerry Seinfeld robbed a loaf of marble rye from a defenseless old lady, and George Costanza pushed aside children and elderly people while trying to escape a fire. Bad choices and selfish behavior, once relegated to supporting characters, took center stage.

The debuts of “Seinfeld” and “The Simpsons” are no less culturally important than Bob Dylan ‘going electric’ at the Newport Folk Festival.

Matt Zoller Seitz, television critic for New York magazine and editor-in-chief of RogerEbert.com, explored this evolution of the TV antihero in a recent article for New York magazine's “Vulture” blog. Reached by phone, Seitz explained that while “selfish jerks” certainly existed before these two series, 1989 was the first time an entire show was built around them. He is, however, quick to point out that the Simpson family does have one redeeming quality: unwavering love for one another. “Arguably,” says Seitz, “that’s the only thing they’re doing right.”

As for “Seinfeld,” “it seemed like it didn’t really care if you liked the characters,” Seitz wrote. “You didn’t get the sense that the show was micromanaging the audience’s responses to the characters and making sure they’re sympathetic.” And that’s what made “Seinfeld” so different from its predecessors: “Even though Archie Bunker [the iconic lead character of “All in the Family”] was a bigot, you sensed there was a nice guy trying to get out.” For the four narcissists anchoring “Seinfeld,” on the other hand, “there was never any hope … That was the joke.”

SUCCESS WAS HARDLY A GUARANTEE. Both series ran just one episode in 1989, and neither seemed destined for greatness at the time. With the knowledge of hindsight, looking back now and viewing those pilots is like flipping through your middle school yearbook and rediscovering your awkward adolescent years en route to maturity. “The Simpsons” evolved from a series of well-liked shorts on FOX’s “The Tracey Ullman Show” to a series kicking off with a Christmas episode that, gambling aside, seems more “Charlie Brown Christmas” special than satirical masterpiece. Likewise, “The Seinfeld Chronicles,” as the pilot was called, looks markedly different from the “Seinfeld” of popular memory; the framing device is familiar — the pilot opens and closes with Jerry Seinfeld in a comedy club performing standup bits — but everything else seems off. Julia Louis-Dreyfus’s Elaine Benes is AWOL. Kramer (originally named Kessler) enters Jerry’s apartment civilly, with few of his trademark slapstick eccentricities. Jerry and his best friend George Costanza mock each other, but also show hints of kindness and camaraderie: “God bless! You devil, you!” exclaims George when Jerry shares news about a new love interest (George even drives Jerry to the airport to pick up said woman — without complaining). The “Seinfeld” pilot received poor reviews from test audiences and mixed reactions from NBC executives, who ordered just four more episodes to air the next year (at the time, the smallest sitcom order in television history).

But the seeds had been planted. “Seinfeld” went on for nine seasons and in 2002 was crowned “the greatest TV show of all time” by TV Guide. It remains one of the most profitable and popular shows in syndication (co-creators Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David reportedly made $400 million apiece for the syndication rights alone) and 16 years after its grand finale, it maintains a strong influence over mainstream humor and lexicon. The show’s unintentional catchphrases — “Yada yada yada” or “These pretzels are making me thirsty” or “No soup for you!” or countless others — are emblazoned on posters across the country. Terms the show popularized — “close-talker,” “re-gift,” “jimmy legs,” “shrinkage,” “man hands,” etc. — have entered everyday vocabulary.

Often, the most shocking topics were slipped in among mundane daily occurrences. “Seinfeld,” in popular memory, is “a show about nothing” — in reality, that was never the case, as Seinfeld and David sold the show to NBC premised on the concept that it would be a series about how a comedian gets his material — which meant some of the most titillating subjects were broached in places that aren’t particularly exciting: over coffee in a corner diner or waiting for a table at a Chinese restaurant. The writers were known for using euphemisms — the male genitalia was often referred to as “it,” sex was “yada yada yada” or “that” — which only added to the show’s self-aware, endlessly quotable hilarity.

They made jokes about the most taboo of subjects — abortion, STDs, the Zapruder film of Kennedy’s assassination, AIDS fundraising walks, terminally ill children — with a wink and a conspiratorial nod. “Seinfeld” viewers, for instance, were first introduced to Newman, the nemesis postal worker, when Kramer complained to Jerry that Newman’s late-night suicide threats were interfering with his sleep: “I said, ‘Look, if you’re gonna kill yourself, do it already and stop bothering me!’ At least I’d respect the guy for accomplishing something.”

Using their likable-but-mean-spirited characters as vehicles, “Seinfeld” and “The Simpsons” pushed boundaries in new, subversive ways. Each flouted political correctness with razor-sharp precision — a radical idea on a major broadcast network when appealing to as wide an audience as possible was the order of the day. Not one thing was sacred, either in the Simpson family’s Springfield or in Jerry Seinfeld’s insular version of New York City.

Even now, 25 years after that Jerry and George talked about button placement, more than 760 thousand Twitter users follow @SeinfeldToday, an account managed by two comedy writers who envision how the timeless show would react to modern social conundrums. One of the account’s most retweeted posts: “Jerry's gf constantly says ‘hashtag.’ George gets a job as a ‘social media expert.’ ‘It's great, Jerry. You don't need to know anything!’”

There is, of course, no need for a “@SimpsonsToday” account on Twitter. The show is soon to start its 26th season and stands alone as the longest-running primetime show in TV history (though its 552 episodes still trail “Gunsmoke” and “Lassie”). “The Simpsons” has produced billions of dollars in merchandising revenue and its imprint on American culture is so large that, according to University of Pennsylvania linguistics professor Mark Liberman, it has “taken over from Shakespeare and the Bible as our culture’s greatest source of idioms, catchphrases, and sundry other textual allusions.”

In its early days, “The Simpsons” dealt mostly in workaday themes: schoolyard bullies, sibling rivalry, marital squabbles, forgotten birthdays. During the first few years in Springfield, the influence of executive producer James L. Brooks — whose balance of humor and heart defined “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “Terms of Endearment,” “Taxi,” and “Broadcast News,” among other projects — is apparent. His track record and impresario status afforded the show a unique privilege: it would not have to receive or implement any “notes” from the network on what should change, what topics should be avoided, and how the show should become more marketable. That freedom allowed the show to marry the Brooksian heartfelt moments with the subversive influence of series creator Matt Groening, and the Harvard Lampoon-induced writing and irreverence of much of its early writing staff.

Offenses on “The Simpsons” have run the gamut over the last quarter-century, especially where Homer is concerned. He tries to pin his drunk-driving accident on his wife. He literally sells his soul to the devil for a doughnut. He repeatedly lets his rage get the better of him, choking his son, Bart, until the kid’s eyes pop out of his head. The dimwitted, lazy, beer-swilling Homer is the classic TV patriarch’s antithesis and worst nightmare — the polar opposite of Bill Cosby’s Dr. Huxtable — and that is a big part of what makes him so funny. His entire parenting philosophy can be summed up in one of his more famous quips: “Kids, you tried your best and you failed miserably. The lesson is: Never try.”

Even in its early years, the show practically bursts with satire and inside jokes. One of Bart’s favorite video games is called “Escape From Grandma’s House.” A halftime show during a Thanksgiving Day NFL game is declares itself “a salute to the greatest hemisphere on earth: the Western Hemisphere!” Homer’s job at the Springfield Nuclear Energy Plant provides ample opportunity for moments of satire, including a three-eyed fish being served at dinner and derailing the gubernatorial ambitions of plant owner Montgomery Burns. Bart and Lisa are beside themselves with laughter when watching “Itchy and Scratchy,” an extraordinarily violent cat-and-mouse cartoon show that serves as a critique both of violence on TV and those who protest violence on TV.

Self-aware humor has been a “Simpsons” calling card since the very beginning. Eagle-eyed “Simpsons” viewers would notice, for example, that Bart’s misspelled “potato” on his science homework offered a quick laugh for those familiar with Vice President Dan Quayle’s similar flub. It was one of many moments of antagonism towards the Bush-Quayle administration, which escalated after both Barbara and George Bush criticized the denizens of Springfield. President Bush gave a campaign speech extolling the family values of “The Waltons” and criticizing those of “The Simpsons.” The writers of “The Simpsons” responded by hastily pasting actual footage of Bush’s Waltons/Simpsons barb into the family’s TV set in the opening scene of the next episode. Bart then returns fire: “Hey, we’re just like The Waltons — we’re praying for an end to the depression, too.”

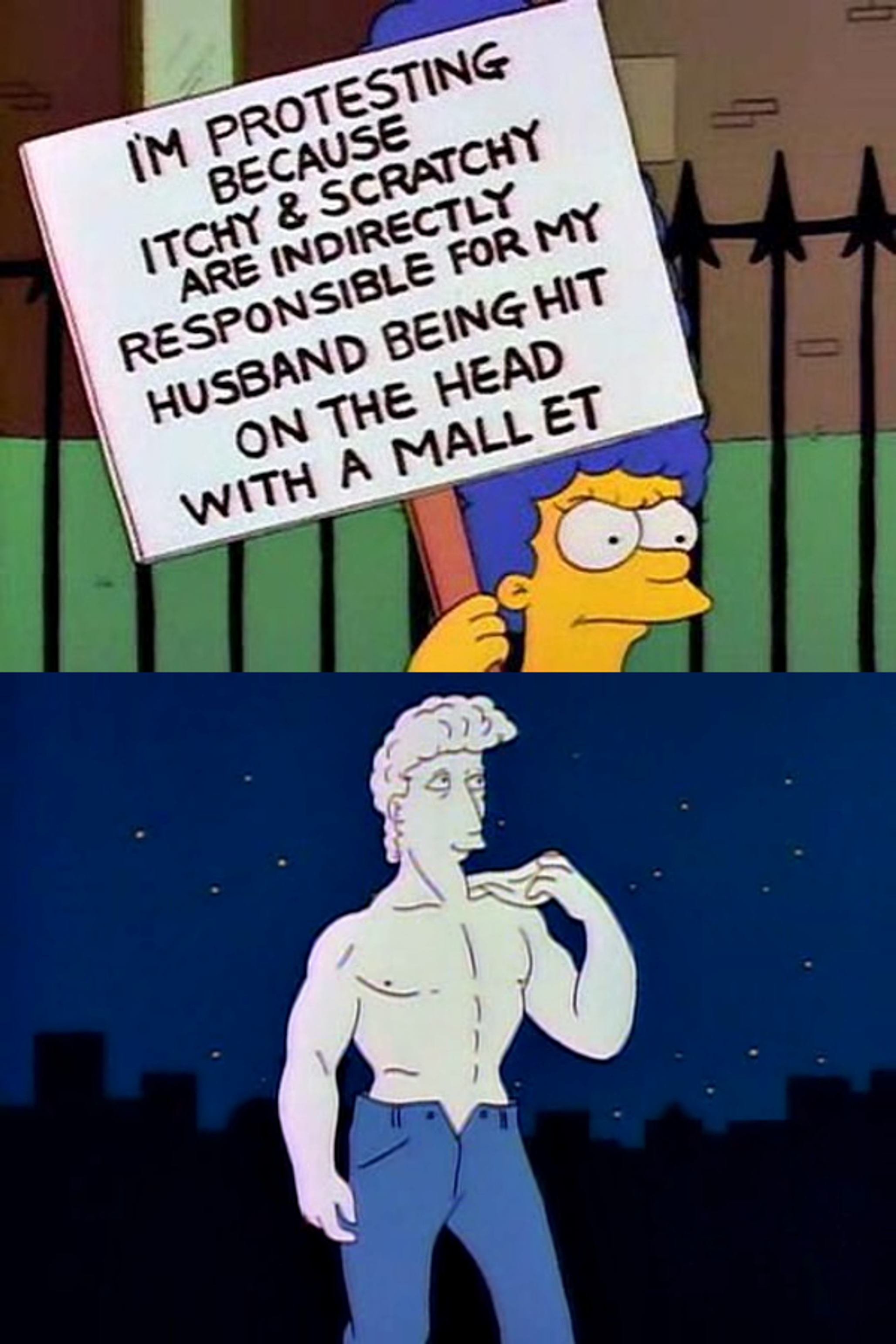

During the show’s second season, Marge becomes concerned about the level of violence in “Itchy and Scratchy,” the über-violent cartoon beloved by Springfield’s kids, after baby Maggie beats Homer senseless with a mallet. Marge leads a picket against the cartoon — her placard memorably reads, “I’m protesting because Itchy & Scratchy are indirectly responsible for my husband being hit on the head with a mallet” — and starts a nebulous pro-censorship group called SNUH (Springfieldians for Nonviolence, Understanding and Helping). Soon enough, she gets invited onto a local TV show to plead her case. “Hello, I’m Kent Brockman, and welcome to another edition of ‘Smartline,’” welcomes the host. “Are cartoons too violent for children? Most people would say, ‘No, of course not. What kind of stupid question is that?’ But one woman says ‘yes’ — Marge Simpson.” Her protest is initially successful — the show is neutered and the children of Springfield are shown emerging outside and having acidly idyllic, Norman Rockwell-esque fun — but the movement grows bigger than Marge. Soon, in its march against vulgarity, SNUH demands that Michelangelo’s David start wearing pants.

Sly jokes, knowing criticism, and a deliriously consistent writing staff helped create some of the most loyal viewers in television history. By constantly referencing its detractors, the show inoculated itself against criticism that it was valueless and vulgar, while turning its audience into co-conspirators by laughing both at the detractors and at themselves. Self-referential and inside jokes from both it and “Seinfeld” have turned both shows into lasting cultural fixtures. As Seitz explains, “the most important relationship is between the show and the audience.”

The writers of “Seinfeld” and “The Simpsons” decided that their audiences deserved to be treated like adults. Instead of pandering or taking the easy way to a happy outcome, they gave loyal viewers intricately woven storylines and extra rewards to superfans who paid close attention. Fans delighted in uncovering layers of meta-humor hidden in each show like so many Russian nesting dolls.

OVER THE YEARS, characters on both series sank to new levels of greed, sloth and self-interest. The “Seinfeld” foursome starts with white lies and garden-variety narcissism, often the sort of thing audience members probably dream of saying, but have the sense not to (e.g. George quits his job in a frenzied rage, telling his boss, “you’re a joke … you’re nothing!”). It wasn’t long before the show was garnering laughs for deplorable behavior: Jerry making out in a theater during a screening of “Schindler’s List,” Elaine hiring a hitman for her neighbor’s dog, Kramer telling George to park in a handicapped spot — “Handicapped people, they don’t even want to park there! They want to be treated just like anybody else. That’s why those spaces are always empty.”

As any “Seinfeld” viewer knows, George was typically the worst offender — lying about his profession (importer/exporter, architect, marine biologist, latex salesman), cheating on an IQ test, hiring a contractor to build a space for napping underneath his desk, and on and on. His pièce de résistance came in the seventh season, when his fiancé Susan died after licking too many cheap, toxic envelopes (chosen by the ever-frugal George) for their wedding invitations. Though Susan’s death was accidental, George’s reaction — a relieved smirk — became one of the show’s most infamous moments. Some viewers were outraged; most laughed. They knew the show was trying to make them uncomfortable, they saw that not even the death of a loved one could change these characters, and therein lay the joke. No hugging. No learning.

In spite of its sarcasm, “The Simpsons” has an earnest soulfulness at its core. As a family, they often hug and learn. Lisa becomes a vegetarian — a lifestyle choice she has stuck with for nearly 20 years while time has otherwise stood still. Bart literally sells his soul only to rediscover its spiritual value, mourn over its loss, and celebrate after he finds that his sister has purchased it back from a third party. Homer has time and again reignited his love for Marge, turned down would-be homewreckers, and dedicated himself to the daily drudgery of his job at the nuclear plant because it provides for his children. In one Mr. Burns posts a sign in Homer’s office reminding, “Don’t forget: you’re here forever,” which Homer pastes over with photos of Baby Maggie, obscuring the letters so that the phrase instead reads “Do it for her”). It is, perhaps, telling that while all “Simpsons” characters have four fingers on each hand, the show subtly depicts God as five-fingered.

What makes these glimpses of genuine love and understanding particularly interesting is that far from seeming cloying, these moments are truly earned. That they take place amidst chaos and nihilism is all the more fascinating (the same episode with Homer’s “do it for her” sign also features Dr. Hibbert listening to Marge’s money woes and reminding that on the black market, “a healthy baby can bring upwards of $60,000”).

One such moment — a fan favorite — happens at the end of “Mother Simpson,” an episode that sees Homer reunite with his long-lost mother. The episode has trademark “Simpsons” comedic bits:

Mother Simpson: (singing) How many roads must a man walk down before you can call him a man?

Homer: Seven!

Lisa: No, Dad, it's a rhetorical question.

Homer: Rhetorical, eh? … Eight!

Lisa: Dad, do you even know what ‘rhetorical’ means?

Homer: Do I know what rhetorical means?!

Yet at the end of the episode, after Mother Simpson has wafted back into Homer’s life, she just as quickly breezes away. Homer is left alone, sitting on the hood of his car and staring at the starry sky in silence. By then, Homer Simpson had found a permanent place in his life, not to mention an enduring place in the hearts and minds of millions of viewers.

THERE WOULD BE NO STOPPING THE SEA CHANGE that followed Homer, Jerry, and company. Antiheroes with questionable (if any) morals soon became the norm, paving the way for iconic TV characters like James Gandolfini’s Tony Soprano, Bryan Cranston’s Walter White, Michael C. Hall’s Dexter Morgan, and Jon Hamm’s Don Draper. Self-aware, sardonic comedies like “Friends,” “The Office,” “Arrested Development,” and “30 Rock” took over (Tina Fey even accepted an Emmy Award for “30 Rock” by sharing her comedic mantra from the podium: “Just try to act like Julia Louis-Dreyfus”). Similar comedic sensibilities carried over from “The Simpsons” into new adult-oriented cartoons like “Family Guy,” “Beavis and Butt-Head,” the “Adult Swim” lineup, and “South Park” (which actually ran an episode titled “The Simpsons Already Did It,” based on the premise that every good story idea had already been used by Matt Groening and company). They all continued down a path blazed by two genre-busting shows and the brave narcissists and brilliant writers who spun them into existence. The debuts of “Seinfeld” and “The Simpsons,” like the debut of "Citizen Kane" or Bob Dylan's ‘electric’ performance at the Newport Folk Festival, expanded the boundaries of genre and medium. Television, comedy, and American culture have permanently changed.

In the end, we find ourselves in a golden age of television. “Nothing gold can stay,” of course, and when this era inevitably loses its lustre, we will always have old episodes of “Seinfeld” or “The Simpsons” to fall back on. In those moments, as now, we can heed the poetic call of one Homer J. Simpson: “Come, family. Let us all bathe in TV’s warm glowing glowy glow.”

* * *

Gina Masullo is a writer and communications consultant who lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Additional contributions by Zack Stanton.

Created in partnership between The Wilson Quarterly and Narratively.