Fall 2019

Inside the Forever Border

– Matthew Longo

Changes in how we police our borders are reshaping the notion of citizenship.

For most Americans, the border is a fairly simple thing. It’s the line that separates us from them; the people on the inside from those who come from somewhere else.

Borders are an institution as old as the states they define. And yet, something feels different these days. Not just for the migrants being shut out, but also for us, as citizens. For many of us, life at home – within the boundaries of our state – feels increasingly constrained, as though the border is closing in on us.

What has happened to make us feel this way? Does it signify a change in borders, in citizenship, or both?

Increasingly, we think of the border in the language of walls. We are in turns irate at the fortress built around us, or thrilled at the protection it might offer. But this is mostly political wordplay – an artifact of heightened language around security, especially emanating from the White House. But a wall doesn’t change the meaning of a border in any real way. It is a thin, vertical edifice, buffering the line as it already exists on the map. Even the metaphors we use don’t change: it is a “line in the sand”; a “good fence” that makes “good neighbors.”

In 2011, former director of the Department of Homeland Security, Janet Napolitano quipped, “you show me a 50-foot wall, and I’ll show you a 51-foot ladder.” It’s a silly line, but it distills an important point: regardless of what our president tells you, walls don’t work. Everybody in the security industry knows this.

To really secure the border, a different approach is needed. And to understand how citizenship is changing, it’s important to start here, with the transformation of the border that is happening before our eyes.

.jpg)

As anyone who has spent time in the U.S./Mexico borderlands can tell you, the border does not look like a wall, or even a line. Instead, what legally constitutes “the border” in the United States extends well inland – up to 100 miles, including from the coast. This is a thick zone of land that includes over 200 million citizens, or fully two-thirds of the U.S. population. It is also a territory in which constitutional protections don’t always apply; a playground for federal officers from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and other agencies, which have tremendous discretionary powers that can be easily abused.

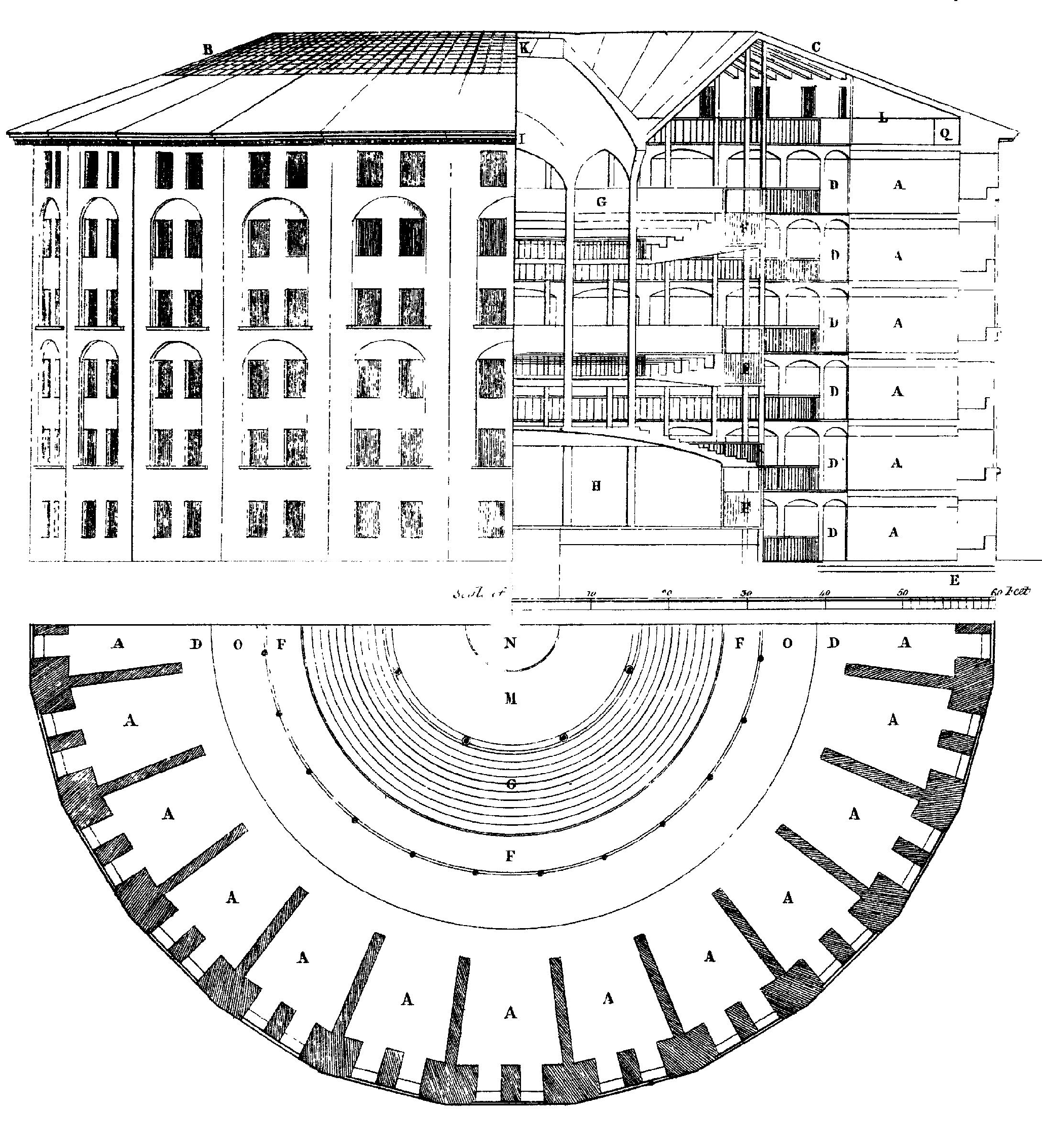

This thick zone boasts cameras and light towers, radars and sensors, drones and balloons. It is a space of surveillance, of a million eyes – a large, open-air Panopticon, fulfilling what philosopher Michel Foucault once called “the oldest dream of the oldest sovereign.” It is a space of filtration and judgment; of discipline and control.

And as the border thickens inward, it expands outward as well, with officials on both sides working together to detect and apprehend threats. This seems counterintuitive: How can guards on the other side look after our sovereign interest as they preserve their own? The concern about competing imperatives is real, but states these days realize they can’t control their borders on their own – even powerful ones like the US. As one former chief of Border Patrol remarked, in our age of globalized mobilities, “you can’t do it alone.”

Cross-border cooperation also makes sense. After all, the threats states face don’t tend to be unique to specific states, but, rather, they are threats to stateness, and their authority – taking forms such as global terror networks, drug cartels, human smuggling rings, and hacking collectives. The imperative to work together generates odd bedfellows: Israel and Egypt do joint raids of the Sinai looking for Islamic radicals (a threat they share in common), just as the U.S. and Mexico conduct joint raids of tunnels attempting to stem the passage of drugs.

In many ways, it would be irrational not to collaborate. In fact, while in our political rhetoric we lionize strong borders – as in President Donald J. Trump’s desire for a “big, beautiful wall” – borders often present an impediment to law enforcement. Think of an old western. A recurrent plot device is that the ‘bad guy’ only has to make it to the county line before he is safe. Once safely out of the jurisdiction, the suspect zips away as the sheriff pulls up and kicks the dirt in disgust. The logic of collaboration is the same: When chasing bad guys, wouldn’t it be good for there to be a sheriff waiting on the other side?

For many of us, life at home – within the boundaries of our state – feels increasingly constrained, as though the border is closing in on us.

After 9/11 it was common to say that we entered “the long war,” a war that was indefinite, that could last forever. These days, we have something akin to a “forever border”. Whereas, in the past, the border was a source of definition and delimitation, the contemporary border is amorphous and undefined. This is not just because it is physically expanding, but because it is entering all aspects of our lives.

What does a forever border look like? The rise of Big Data in state decision-making means that every citizen is not just surveilled at the border, but increasingly can be monitored through every form of interaction – from texts and cellphone calls, to bank transactions and online shopping expenditures. Every day, we give off signals of who we are – including behavioral and reputational data, culled from social media – which the state uses to generate risk-ratings aimed at flagging suspected terrorists and illegal aliens. Or just people it deems risky.

And of course, with these programs, minorities are directly and disproportionately targeted. Some of this is an artifact of technology – facial recognition software, for example, consistently misidentifies people of color. But some is political. One clear example is a government program like “E-Verify,” designed to make sure that job applicants have documentation before they can be given work contracts. This, too, is a kind of gate-keeping, performed not at a national border, but everywhere that people work. It is the data version of a “papers, please” law – evidence that the border isn’t just around us, it is within us too.

It may also explain the feeling that border is closing in on us.

People of the Forever Border

These two kinds of bordering – the expansion of the physical border, and the use of data in internal surveillance – are developing in tandem. But the feeling of being increasingly squeezed by the border is not felt equally among citizens.

The Other Within

After 9/11, a security spotlight was focused upon Arab Americans – and Muslims of any sort – with a strength and speed theretofore unimaginable. Mosques and Muslim community centers became a new ground zero of discriminatory attention.

The late American comedian Robin Williams even made it a part of his act, describing blacks and Hispanics at an enhanced airport security queue joking that it was now “Habib’s” turn to face the scrutiny previously meted out on them. Overnight, a segregative language emerged about the threat that they posed to us, even though, as citizens, they were part of us too.

If it wasn’t already clear that U.S. citizenship had several classes, it was never clearer than in that moment. The sweeping nature of state surveillance, and especially the newfound powers afforded by Big Data to identify suspects before they even acted, was immediately on display. Corporate entities fell over one another offering their data analysis capabilities in the service of this new all-encompassing security enterprise. By mining databanks, they could assemble complex threads, linking individuals to risky behavior. So if, for example, you purchased 200 pounds of fertilizer and, in the same month, called Pakistan, they knew who you were.

.jpg)

Imagine yourself in the shoes of one of the millions of Americans profiled in this way. What does life look like in this kind of forever borderscape? Certainly, your every move is watched. We all give off data records, but in the realm of data, discrimination is the name of the game. In an Orwellian spin, we might say that vis-à-vis data, some people are more equal than others. It’s not all calls, its calls to Pakistan; it isn’t all Pakistanis, it’s the one whose additional behavior (like buying fertilizer) flags them as risky.

The key point is that this sort of surveillance doesn’t privilege one’s status as a citizen. Think of the arrivals terminal at a U.S. airport. Business class travelers from around the world zip through with their global access passes and frequent traveler memberships, while American citizens of ethnic backgrounds are more frequently stopped and interrogated – even when returning to their own states. These citizens quickly discover their passport doesn’t necessarily help them, since it plays only a tiny role in the constitution of a risk rating.

In other words: in the age of Big Data, risk is what determines whether your citizenship is meaningful. Citizenship as such has all but lost its value.

Inside the Control Zone

Ethnicity is not the only way that citizens attract increased attention from the state. Citizens who live in the borderzone, and especially the 100-mile stretch of U.S. soil adjacent to the US-Mexico border, are more scrutinized than others. You don’t need to have called Pakistan or bought high volumes of fertilizer. Here you are instantly suspect, not because of your ethnicity – millions of non-Hispanic citizens live in this zone – but simply because of your place of residence.

To be sure, there is an ethnic dimension here too, given the large population of Mexican-Americans. In fact, a giant proportion of the border force is comprised of Mexican-Americans, determined to enforce the distinction between themselves (American citizens), and co-ethnics who live on the other side. But discipline in the borderlands doesn’t distill to race. All citizens are forced to endure high levels of surveillance, with cameras at every corner, and routine stops and searches of cars, as well as an inordinate density of security officials including, local, state, and federal officials – and, on occasion, even National Guard.

Border citizens – all border citizens – are asked to bear the weight of national identity. Border Patrol recruits directly from local civilian populations in the borderlands, starting even before high school with special programs designed to drum up interest. Border Patrol also does outreach in local schools to make sure students have their ears to the ground, to report leads on suspect behavior – to make sure communities police each other, so as to help law enforcement police them.

In the borderlands, the state wants to know: What have you seen? Who do you know? (And, implicitly, why should we trust you?) All populations these days are to some degree tasked with this – think of messages like “if you see something, say something.” But in the borderlands, this demand upon citizens is far more direct. You are the nation’s first line of defense, including against your own neighbors. Any student of totalitarian politics will recognize this tactic. If ever citizenship were conditioned upon loyalty, it is here.

The Average Joe in the Sights

The indefinite and unlimited nature of the forever border has the potential to sweep up everyone in its view. With Big Data, states can screen, sort, and assess individual citizens, with the aim of generating a totalizing, “360-degree” profile, thereby measuring their overall trustworthiness.

This information squeeze raises many concerns. Even the best algorithms render considerable errors when scaled over hundreds of millions of people. One analyst I interviewed for my research explained: “My fear is that the accidental dissemination of incorrect data could ruin someone’s identity … You are putting some confidence in that algorithm. None of them are perfect. They make mistakes.”

Yet the problem is also political. After all, data systems are designed by people and embody the values we give them. Security algorithms tend to be overly sensitive, picking up more threats than the state can even process. This makes sense from the vantage of the state which would rather gather more data, even at the risk of multiplying errors (and potentially compromising identities). As citizens, this may leave us out in the cold.

In democratic societies, security protocols remain largely circumscribed by constitutional protections. But how long can these hold, given the persistent creep of security installations? This concern is embodied by China, a technologically-advanced society in which citizenship has changed meaning entirely. Their newly-piloted “citizenship score” system offers social “goods” to those considered loyal to the regime, and penalizes those who, say, make political posts online, or contradict the government.

In the age of Big Data, risk is what determines whether your citizenship is meaningful.

This is markedly different than the ways that the state and other institutions use data in the U.S. But should we be confident that it couldn’t happen here? After all, the underlying logic of the two systems is the same. Both use data to establish trustworthiness. Both make citizenship something that has differential value based on who you are and how you behave. This doesn’t just affect specific citizens; it affects everyone.

In this new world of forever bordering, everyone is potentially suspect, and may one day draw the eye of state security. Most of us, to some degree or another, already do.

Shoring Up Citizenship

In democracies, the people are supposed to be sovereign, with the state acting in their service. This is the basis of the state’s legitimacy. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote in the 18th Century: “the words subject and sovereign are identical correlatives, whose meaning is combined in the single word ‘citizen.’” The key to this citizenship is the harmony of obedience and liberty. It cannot be sustained if we are more subservient than we are free.

Citizenship is a fragile thing. Left alone, the trends in border security discussed here are poised to erode any normative basis of citizenship that still remains. The warning signs are already present, in our time of relative stability. Should a pervasive shock or crisis hit, risk metrics will prove an ideal means of targeting specific members of the polity (usually minorities) ever more ruthlessly.

We have a history of this: it is not too long ago that Japanese Americans were interned – with the blessing of the Supreme Court, decided in 1944 in Korematsu v. United States – forcibly taken from their lives as loyal, tax-paying citizens, and vilified as potential enemy informants overnight. This could happen again, and if it does, the last meaningful threads of citizenship will be torn away.

Reclaiming a citizenship that is no longer secondary to risk – or subordinate to it – must be a priority. Given our security-obsessed age, and the realities of the forever border, this won’t be easy. But if we don’t fight for our rights now, they won’t be around too much longer.

Matthew Longo is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Leiden University and author of The Politics of Borders: Sovereignty, Security, and the Citizen after 9/11 (Cambridge University Press).

COVER: Downtown El Paso, Texas, as seen from the Paso del Norte International Bridge. The bridge links El Paso to Ciudad Juárez in Mexico. (Photo by Sergio Chapa / Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera)