Fall 2007

Intelligence Tests

– David J. Garrow

David J. Garrow on the intelligence community.

Rare is the book that receives an official response from the U.S. government. This past summer, the Central Intelligence Agency angrily greeted the publication of Tim Weiner’s Legacy of Ashes with a lengthy press release fashioned on taxpayer-funded time. Through “selective citations, sweeping assertions, and a fascination with the negative,” the CIA complained, “Weiner overlooks, minimizes, or distorts agency achievements.” That the agency devoted personnel resources to write its own review is a testament not only to the reputation and accomplishments of the book’s author, a New York Times reporter who has covered the American intelligence community for two decades, but also to the intense scrutiny that community has endured in the years since September 11, 2001. In fact, the CIA’s conspicuously defensive stance is fully in keeping with its entire history.

Many attentive people may think that the CIA was vastly more successful and skillful in the 1950s and ’60s than it has been over the past quarter-century, but Weiner proves otherwise in this impressively comprehensive history, which relies on more than 300 interviews with CIA officers and veterans as well as a sizable trove of recently declassified material. Right from its creation in 1947, the CIA spawned one disaster after another: first sending literally “thousands of foreign agents to their deaths” in ill-planned efforts to insert anticommunists behind Soviet lines in the early years of the Cold War, then failing to foresee both the outbreak in 1950 of the Korean War and, soon after, a sudden Chinese onslaught across the China-Korea border that inflicted massive U.S. casualties. Not one of the 200 CIA officers stationed in Seoul during the war spoke Korean.

Agency-sponsored coups in 1953 and ’54 that overthrew the governments of Iran and Guatemala are among the CIA’s most storied exploits, but Weiner persuasively contends that neither adventure redounded to America’s advantage because both countries quickly fell under the rule of repressive regimes. Nonetheless, the two coups “created the legend that the CIA was a silver bullet in the arsenal of democracy,” Weiner writes. As former U.S. ambassador to South Korea Donald Gregg explained, “The agency had a terrible record in its early days—a great reputation and a terrible record.”

The 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco, in which CIA-trained Cuban exiles botched an invasion of their homeland, revealed the agency’s ineptitude at its worst, and on October 4 the following year, at the onset of the Cuban Missile Crisis, “99 Soviet nuclear warheads came into Cuba undetected.” Those disasters did not dissuade John and Robert Kennedy from dispatching CIA covert operators hither and yon, especially in other futile efforts to oust Fidel Castro, and in the aftermath of John Kennedy’s assassination the agency “hid much of what it knew” about the Kennedys’ anti-Castro plots from new president Lyndon Johnson.

If the CIA’s covert paramilitary record was abysmal, its anti-Soviet espionage efforts were no better. “Over the whole course of the Cold War,” Weiner recounts, the agency “controlled precisely three agents who were able to provide secrets of lasting value on the Soviet military threat,” and all were exposed and executed as a result of sloppy tradecraft and Soviet penetrations of U.S. intelligence. The CIA could not duplicate our enemies’ success at infiltration: During the Vietnam War, for example, it failed to penetrate the North Vietnamese government in any fashion. And because it refused to deliver bad news to the Johnson White House, which had a pronounced distaste for such reports, the agency’s war analyses became politically debased.

Weiner does credit an atypical 1966 CIA report, The Vietnamese Communists’ Will to Persist, with greatly influencing Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to turn away from rosy expectations of U.S. triumph in Vietnam. This is just one of many particulars related in the book that belie the CIA’s charge that Weiner’s “bias overwhelms his scholarship.” But the politicization of the agency’s analytical reporting continued apace throughout the 1970s and ’80s, particularly in its wildly overstated estimates of Soviet economic strength and the size of Moscow’s nuclear arsenal.

The agency’s problems got even worse when William Casey took the reins under President Ronald Reagan in 1981. The Iran-Contra weapons-for-hostages scandal reflected what Weiner calls “a culture of deceit and self-deception at the CIA,” a disease that metastasized in the late 1980s and early ’90s, when the CIA knowingly passed to the White House reports whose sources were Moscow controlled but that it used nonetheless—and “deliberately concealed that fact.” The CIA had no advance clue whatsoever about the decline and implosion of the Soviet Union between 1989 and 1991, and the sudden end of the Cold War left the agency without a clear agenda for the following decade. It was embarrassingly slow to grasp the growing danger of Islamic terrorism. In the mid-1990s, Weiner reports, “a total of three people in the American intelligence community had the linguistic ability to understand excited Muslims talking to each other.”

Legacy of Ashes thus demonstrates that the two infamous intelligence tragedies of this decade—the failure to prevent the 9/11 attacks and the false reports of Iraqi biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons programs—were not idiosyncratic or exceptional errors. Instead, they were wholly in keeping with the CIA’s history. On Iraq, Weiner emphasizes, the CIA delivered bad information not for “political reasons” involving a desire to curry favor with Bush administration leaders, but because of sheer incompetence: “The CIA had based its conclusions on Iraqi biological weapons on one source,” an Iraqi defector bent on Saddam Hussein’s ouster, and its findings about chemical weapons on “misinterpreted pictures of Iraqi tanker trucks.” Contradictory information from a French intelligence source (Iraqi foreign minister Naji Sabri) “that Saddam did not have an active nuclear or biological weapons program” was brushed aside.

Reform efforts since 2001, including the creation of the post of “intelligence czar” for oversight of the nation’s 16 intelligence agencies (formerly a function of the CIA director), actually represent “continuity masquerading as change,” Weiner argues. Today, despite huge budget increases, the agency has “the weakest cadre of spies and analysts in the history of the CIA,” and many of its traditional clandestine activities have been usurped by the Pentagon, whose own intelligence capabilities have mushroomed since the 1991 Gulf War. In the years since, the agency has been downgraded to a “second-echelon field office for the Pentagon,” tasked with fulfilling Defense Department information requests.

But in another new book, Amy Zegart, a political scientist at UCLA, argues that any meaningful improvement in U.S. intelligence coordination and effectiveness will require the president and Congress to take on the Defense Department rather than accede to its dominance. That would be no small job. So as to maintain the independence of the Defense Department’s intelligence operations, “Pentagon officials and their turf-conscious congressional supporters have been torpedoing intelligence reform forever,” Zegart bluntly complained in The Washington Post this summer.

Spying Blind is a thorough examination of those reform failures. In it, Zegart sifts through hundreds of intelligence recommendations in a dozen reports between 1991 and 2001, and findings by the 9/11 Commission and congressional committees in the years since. She concludes that not only was 9/11 insufficient “to jolt U.S. intelligence agencies out of their Cold War past,” but also that “future adaptation—to terrorism or any other threat—is unlikely.” Her pessimism is rooted in both the military’s understandable desire to focus intelligence resources on short-term tactical needs, rather than longterm strategic analysis, and the Pentagon’s political stranglehold on reform efforts.

The 2004 law that created the so-called intelligence czar, Zegart explains, “triggered a scramble for turf that has left the secretary of defense with greater power, the director of national intelligence with little, and the intelligence community even more disjointed” than it was before 9/11. The new position simply adds one more bureaucratic layer to the existing multiplicity of separate entities. The government’s continuing inability to impose centralized management on the entire intelligence community, she believes, is “disastrous.”

Zegart deplores the consensus view that lays the failures of September 11 at the feet of individuals in both the CIA and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. If success and failure hung on individual leaders, she says, fixing intelligence agencies would be easy. The real causes of failure are organizational. For example, Zegart credits the FBI with realizing, before 9/11, that its internal information sharing and case coordination needed dramatic improvement. But, as she cogently recapitulates, the Bureau failed to act on clues various agents had identified that pointed to the impending attacks.

Neither Spying Blind nor Legacy of Ashes devotes as much attention as it might to what, currently, is perhaps the most pressing and widely overlooked intelligence policy issue: the increasingly common outsourcing of thousands of traditional government jobs to private companies headed by recent retirees from the CIA and other agencies. (The Spy Who Billed Me, a blog by political scientist R. J. Hillhouse, is a most instructive source on this trend.) Weiner does remark that “patriotism for profit” has become such a growth industry that the CIA in effect has “two workforces,” and corporate employees are far better paid than public ones. “Jumping ship in the middle of a war to make a killing” is so appealing, he asserts, that the CIA faces “an ever-accelerating brain drain.”

If the privatization of government intelligence work is so grave a problem, congressional inquiry and prompt policy change appear imperative. Yet though Legacy of Ashes and Spying Blind demonstrate that the U.S. intelligence community remains embarrassingly substandard, both books also make plain that the chances for meaningful improvement are virtually nil.

* * *

David J. Garrow is a senior fellow at Homerton College, Cambridge University, and the author of The FBI and Martin Luther King Jr. (1981), among other books.

Reviewed: “Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA” by Tim Weiner, Doubleday, 2007. “Spying Blind: The CIA, the FBI, and the Origins of 9/11” by Amy B. Zegart, Princeton University Press, 2007.

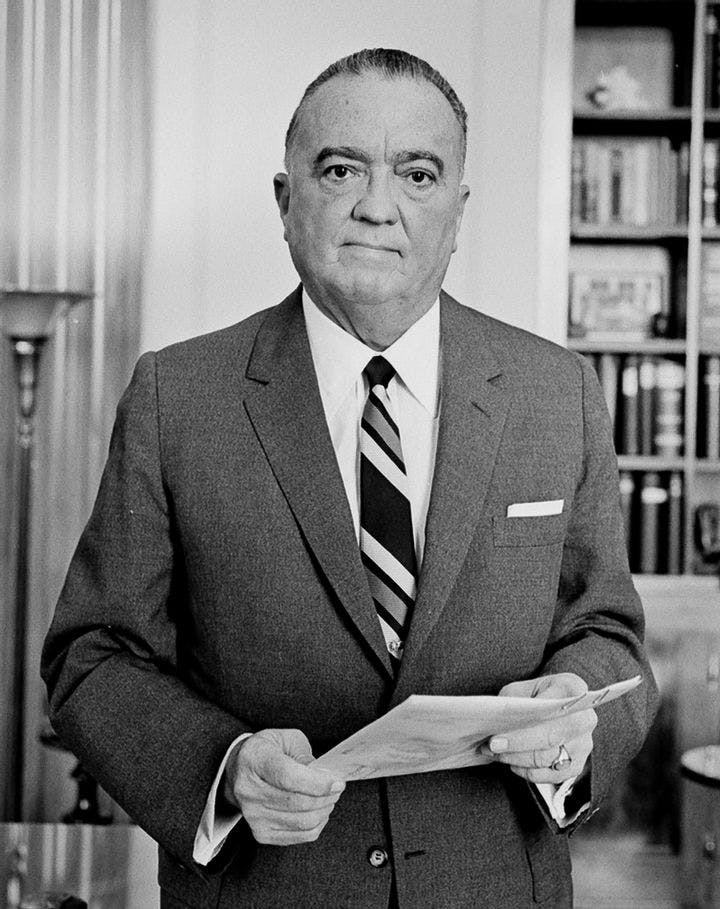

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress