The Islamic State’s “Ashley Madison” way of war

– Grayson Clary

Why do we have such a difficult time seeing data leaks as a paramilitary tool?

On December 11, 2015, Islamic State supporters published the home addresses of dozens of national security officials. It isn’t clear that the details are authentic, or that they were gathered via anything more sophisticated than Google, but the move marked a growing interest in low-grade digital conflict — the spread of an Ashley Madison way of war.

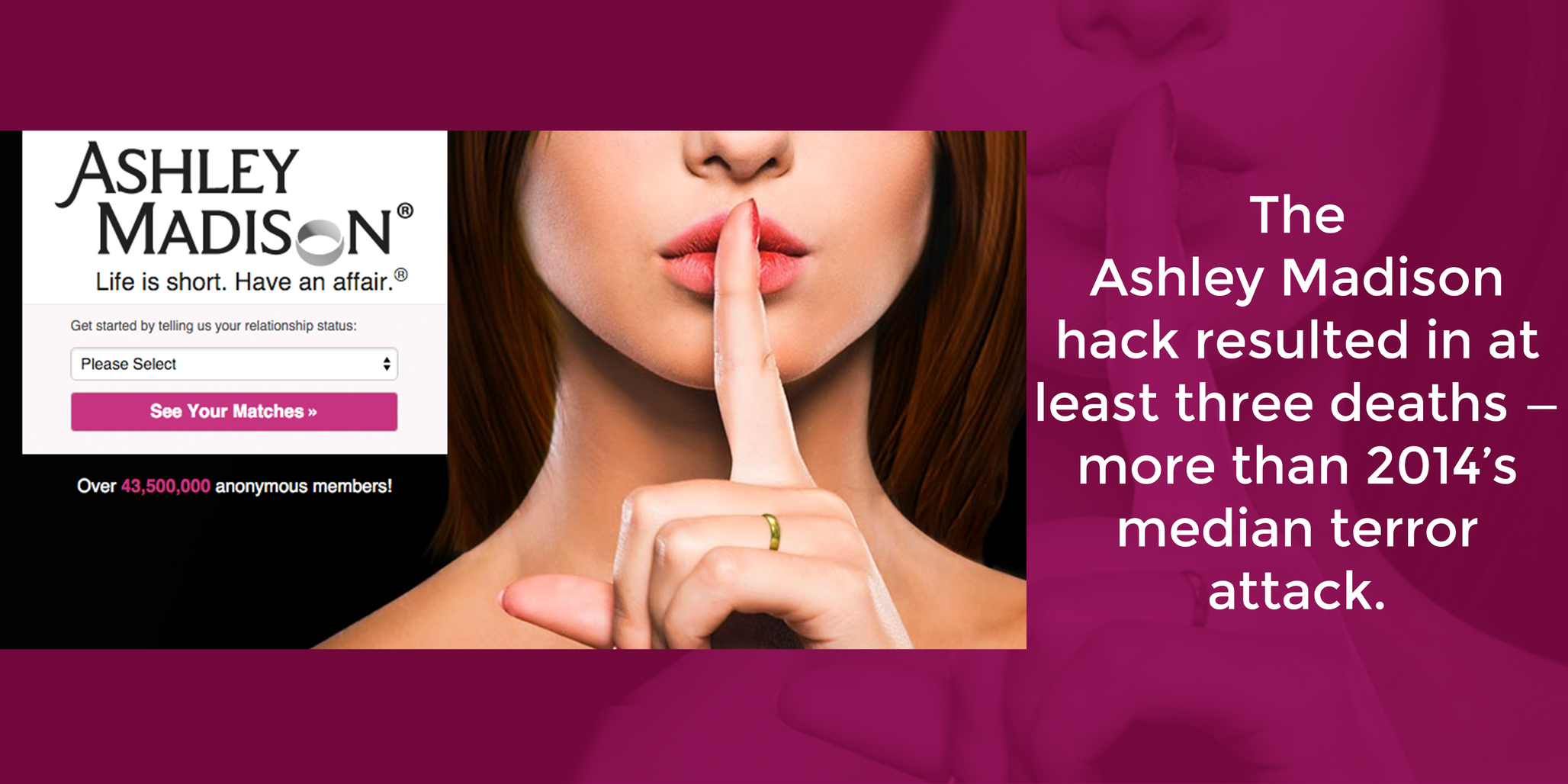

In August, hackers calling themselves Impact Team disclosed the transaction records of some 32 million Ashley Madison users who had been seeking extramarital affairs through the service. Parsing more than four months of fallout, it seems more and more appropriate to view that leak as a groundbreaking act of information terrorism. Fusion’s Kristen Brown tallied the casualties in an investigation published last month: “at least three suicides, two toppled family values evangelists, one ousted small-town mayor, a disgraced state prosecutor, and countless stories of extortion and divorce.” If a little data can be a dangerous thing, that unfortunate collection was a weapon of mass destruction.

If a little data can be a dangerous thing, the Ashley Madison hack was a weapon of mass destruction.

But insofar as observers saw the dump as a national security story, it was almost always approached as either a cybersecurity incident or — given the .mil and .gov addresses in the dataset — a counterintelligence issue. Those views missed the significance of a novel, remarkably lethal disclosure. Consistent with examples set this year by hacktivists and the Islamic State, the leak pointed toward new frontiers in open-sourcing the kill chain. After all, the event was deadlier than the median terror attack, which in 2014, according to the State Department’s Country Reports on Terrorism, resulted in just 2.57 fatalities.

If we have a difficult time seeing leaks as a paramilitary tool, chalk it up to two factors. First, alarmism about “cyberwar” steers attention toward rare, unusually talented hackers and rare, unusually high-impact scenarios. The majority of the damage done online — authored by low-skill individuals in endless minor incidents — struggles to bid for the same coverage, even if its aggregate effect is larger. Second, even when we grant that a good dataset can do harm, the connection between payload and targeting package is often obscure or unpredictable, even to the individual who deploys it. In other words, this kind of assault can look less like laser-designating an airstrike than it does like praying for lightning to strike. For both reasons, we tend not to see raw data as a directed weapon.

But that attitude is less and less tenable. Doxxing — the malicious disclosure of personal information — may be an old Internet habit, ancient by web standards, but we live in its golden age, a moment in which its ties to physical, political violence are tighter than ever.

The Ashley Madison leak was the deadliest example in 2015, though it was also one of the least sophisticated. That breach had a low-tech sting, leveraging the Internet’s signature surplus commodity: shame. While the ensuing suicides were tragically predictable, they also represented very low lethality: three casualties out of more than 30 million targets. More innovative are those campaigns that use personal information to bid a for a third-party’s intervention. Pioneers include the Islamic State and the hacktivist collective Anonymous, which for months have been locked in a “war” fought with doxes.

That conflict surged to mass attention after November’s attacks in Paris, which prompted Anonymous to launch #OpParis, an effort to identify Islamic State sympathizers on social media. And while talk of a “cyber war” between Anonymous and Islamic State fed the impression that expert hackers were squaring off, little tech-savvy was ever involved.

Instead, #OpParis depends on the distributed effort of average Internet users. A landing page for the fight offered a “NoobGuide” to hacking — “you should be able to understand it fully and there’s nothing hard” — as well as code snippets that make it easier to identify and monitor jihadists on Twitter. A strong command of copy/paste would get you started, which Anonymous never tried to hide. “Your contribution means a lot,” the guide read, “and we encourage you to partake in all of the Op’s activities if you can, the more the merrier.” In this case, those activities amounted to open-source intelligence collection. As Brian Feldman reported for New York magazine, the chat channel for #OpParis warned against anything more disruptive than that: “No DDOS/Defacing, just collect targets!”

But if #OpParis is tough to fault — civil, civic, anti-extremist — it still highlights the extent to which non-state groups can weaponize information today. While Anonymous’ goal is to get accounts taken down, Western intelligence officers can think of other uses for the information. Tweets often figure in the indictments of Islamic State sympathizers; in November, in the first case of its kind, an individual was charged for allegedly sharing an animated GIF image on Tumblr. And in at least one instance, the U.S. used a jihadist selfie to target an airstrike. Whether or not it means to be, Anonymous is a de facto partner in those efforts.

This is the kinetic flipside of a broader open-source revolution. Just as spy agencies can now draw on citizen or social media espionage, doxxers can rely on distant authorities to provide legal or military force. In a way, it’s an extension of swatting — the practice of calling in a fake crime to draw a traumatic SWAT response — into the domain of national security. Of course, the dynamic also powers the Islamic State’s ability to direct lone wolf attacks by doxxing service members and other Western officials. As the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center warned in a November bulletin, “Law enforcement personnel and public officials may be at increased risk of being targeted by hacktivists.”

Can this kind of information warfare be countered? On a policy level, it seems unlikely and unwarranted, especially in cases where the information gathered is gathered legally. Democracies rightly place a premium on the free flow of information, which makes this sort of assault — powered by speech and fact — hard to imagine blocking. More likely, these dox incidents will increasingly be the daily background radiation of modern war.

Most solutions will be personal and organizational, as the Islamic State’s was after Anonymous launched #OpParis. It stressed that its members would need to practice better operational security, maintaining close control over their personal data wherever possible.

We could all do more to adapt our situational awareness to a world in which, as former NSA and CIA Director Michael Hayden puts it, “We kill people based on metadata.”

* * *

Grayson Clary is a research associate with the Digital Futures Project at the Wilson Center.