Summer 2011

My Favorite Civil War Novels

– David S. Reynolds

A few well-crafted novels bring alive what Walt Whitman called “the seething hell and black infernal background” of the war.

The real war will never get into the books.” So wrote Walt Whitman, who witnessed the Civil War close up as a volunteer nurse in war hospitals in Washington, D.C. As effective as his war writings are, one can read them and yet acknowledge the truth of his point about the war never being fully represented in words. Tens of thousands of Civil War books later, his declaration still holds true. But fiction gives us a visceral understanding of what Whitman called “the seething hell and black infernal background” of the war. Well-crafted novels bring alive the richly textured atmosphere and varied personalities of the war in a way that even the best journalism and history books can’t. A number of masterly fiction writers have used the bleak context of the Civil War to offer profound insights into the human condition. Here are my favorite Civil War novels.

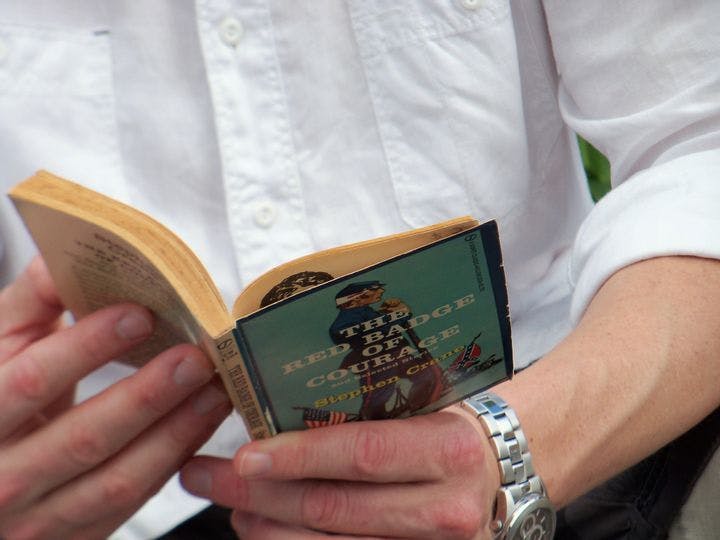

The Red Badge of Courage (1895)

Stephen Crane (1871–1900), a minister’s son born several years after Appomattox, wrote one of the great war novels of all time when he was scarcely more than a boy. In The Red Badge of Courage, he produced powerful war scenes by imaginatively embellishing stories he had heard and read. His brother William, with whom he lived for several years, was an attorney who had schooled himself on the Battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, and young Stephen had studied books such as Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (1887–88).

The hero of The Red Badge of Courage is Union Army private Henry Fleming, whom Crane refers to as “the youth.” Tossed by moods and emotions in the campground and on the battlefield, Fleming works his way through cowardice and terror, gaining a sense of manhood after being tried in the crucible of combat. The battle described in the novel is commonly thought to be that of Chancellorsville, but, like the Army officers who appear briefly, it is not named. Crane was uninterested in the specifics of history. The battle he portrays—a murky chaos of smoke, whistling bullets, and soldiers dropping “like bundles”—could be any Civil War engagement, and Henry Fleming is the universal soldier.

The Killer Angels (1974)

In The Killer Angels, Michael Shaara (1928–88) dramatizes the activities of well-known participants in the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. He etches detailed portraits of the Confederate generals, including Robert E. Lee, James Longstreet, J. E. B. Stuart, George Pickett, and Jubal Early, and, on the Union side, officers such as Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, John Buford, and George Meade.

Shaara strips the generals of their mythic trappings and makes them accessibly human. The reserved, blunt Lee has a surprising aversion to slavery and is guided by a Christian conscience. An aggressive warrior who believes in well-organized frontal assaults, he differs from his second in command, Longstreet, who prefers defensive maneuvers, and from Pickett, a dandyish tyro whose hunger for military action fuels his famous, doomed charge across an open field.

A stickler for fact, Shaara provides maps that show the positions of the opposing armies on successive days of the battle. His style has the understated directness of Ernest Hemingway and the sensitivity to human thought patterns reflected in the works of James Joyce and William Faulkner.

After Shaara’s death from a heart attack in 1988, his son, Jeffrey, wrote Gods and Generals, a prequel to The Killer Angels, as well as a sequel, The Last Full Measure, and other war novels. All of them were bestsellers, but none approach the magnificence of the original.

Love and War (1984)

John Jakes’s entertaining popcorn epic is part of a sprawling trilogy that spans the entire Civil War as it follows the lives of two families: the Mains, South Carolina rice planters, and the Hazards, Pennsylvania steel manufacturers. Linked by friendship and marriage, the families serve as windows on sectional tensions that escalated in the antebellum period (the subject of North and South, the first novel in the trilogy), flamed into bloody conflict (Love and War), and persisted during Reconstruction (Heaven and Hell). Jakes has turned his historical family sagas into something of a cottage industry—he’s written 18 consecutive New York Times bestsellers—but his Civil War trilogy has a dramatic, human quality that even those who turn up their noses at popular fiction find compelling.

All three novels in the trilogy are terrific, but Love and War is the most obvious choice for war buffs. Its cast of characters includes the famous—Lincoln, Lee, and Jefferson Davis among them—as well as the unfamiliar and the purely fictional. Jakes has said in interviews that he toured battle sites, read scores of history books, and pored over The War of the Rebellion, a mammoth collection of primary documents of both the Union and Confederate armies. Even his flights of fancy—as in his whimsical account of a radical secessionist plot to assassinate Davis and establish a Pacific Confederacy—come across as credible.

Although Jakes’s stated goal of challenging romanticized renditions of the war such as Gone With the Wind (1936) is disingenuous—after all, many writers have revealed the war’s horror and banality—the book has the feel of history experienced at ground level. Jakes interweaves graphic renderings of Civil War battles with a plot that involves corruption, betrayal, and illicit sex. Small wonder that this thousand-odd-page novel was adapted into an ABC miniseries, North and South, Book II, starring marquee actors such as Hal Holbrook, Patrick Swayze, and Lesley-Anne Down.

The March (2005)

My choice of a fourth favorite Civil War novel is a tossup between The March, by E. L. Doctorow, a virtuoso writer who once served in the U.S. Army, and the similarly titled and nearly contemporaneous March, by former journalist Geraldine Brooks. Brooks spins an imaginary tale around the war experiences of Mr. March, the father in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, who leaves his family to serve in the Union Army. I tip the scales toward Doctorow because he cleverly turns the tables on Gone With the Wind, that staple of Civil War literature, by depicting William Tecumseh Sherman’s historic march through Georgia and South Carolina from an anything-but-romantic angle.

In The March, E.L. Doctorow turns the table on Gone With the Wind, that staple of Civil War literature, by depicting William Tecumseh Sherman's historic march from an anything-but-romantic angle.

Doctorow renders the Union Army as a gargantuan, slug-like creature moving inexorably along as Sherman deploys his scorched-earth tactics—stealing livestock, pillaging homes, and burning cities and plantations. Sherman himself, the “small brain” of this monster, is far from general-like. A tall, bristle-chinned, ungainly plebian whose legs almost touch the ground when he sits on his horse, Sherman justifies his actions on the principle that war is hell.

Given this outlook, Doctorow could have produced a predictable tale about war’s grim determinism. But part of his novel’s magic lies in how its unusual characters—including two comical Southern stragglers who save themselves by donning enemy uniforms, a proud ex-slave who captivates a Union soldier, and a prim Georgia socialite who gives herself to a charismatic Union field surgeon—provide fresh perspectives on the devastating campaign that was the death blow to the South.

* * *

David S. Reynolds is an English professor at the City University of New York Graduate Center. His books include Walt Whitman's America (1995), John Brown, Abolitionist (2005), Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson (2008), and Mightier Than the Sword: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Battle for America, which has just been published.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Summer Skyes 11