For poor women, barriers to birth control access could soon get worse

– Miriam Kelberg

As Congress considers a budget that would cut funding for family planning, it’s worth remembering the difficulties that many women face in accessing contraceptives — and why that access is so important.

In New York’s Times Square, gigantic video billboards illuminate the words: “#BirthControlHelpedMe have my son.” Planned Parenthood is leading this neon-lit campaign, a rallying cry in response to a congressional budget proposal that eliminates funding for Title X Family Planning. Encouraged by the ad campaign, some women are taking to social media with the hashtag #BirthControlHelpedMe to share their personal testimonies of the importance of access to contraceptives. “#BirthControlHelpedMe determine that I could be the most independent woman I wanted to be” shared one woman. “BirthControlHelpedMe raise and provide for the 2 children I chose to have,” shared another.

They are not alone.

In a recent Guttmacher Institute study, a majority of women stated that birth control enables them to support themselves financially (56 percent), complete their education (51 percent), take better care of themselves and their families (63 percent), and get or keep a job (50 percent). Among women with incomes under $75,000, 44 percent reported that they want to limit or delay their childbearing because of economic hardship. For that to happen, birth control is essential.

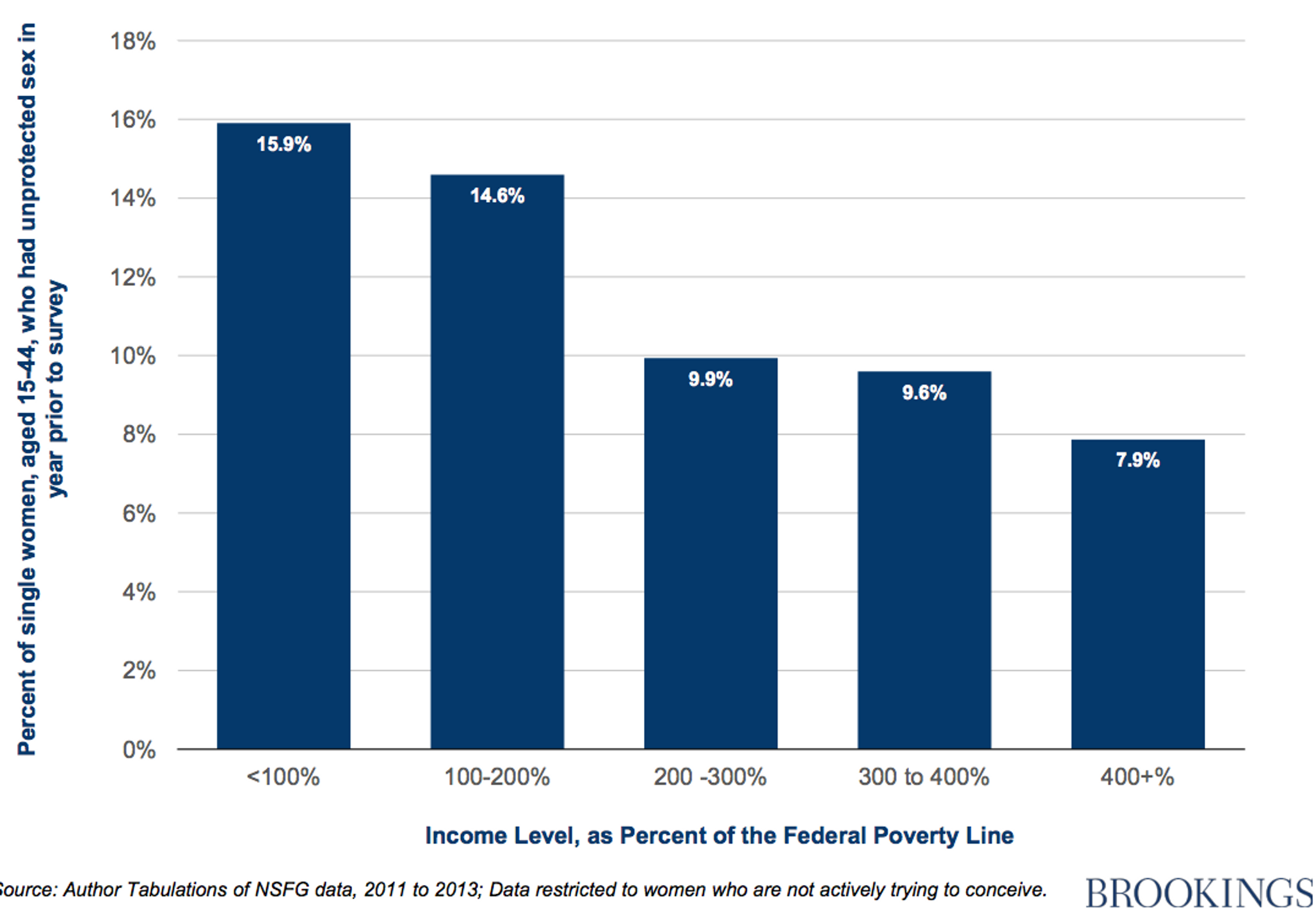

When birth control is unavailable, poverty becomes cyclical. Impoverished women are less able to choose when and how many children they have. Oftentimes, those children are raised in poverty, and will grow to experience similar disparities. Brookings Institution experts Richard Reeves and Joanna Venator have found that the lower a woman’s income, the less likely she is to use contraceptives. Compared to their wealthier counterparts, rates of unintended pregnancy are much higher among women who belong to demographic groups that traditionally have limited social mobility — women of color and women with lower levels of educational attainment, for instance — further entrapping disadvantaged women and committing their children into cyclical poverty.

Access and Affordability

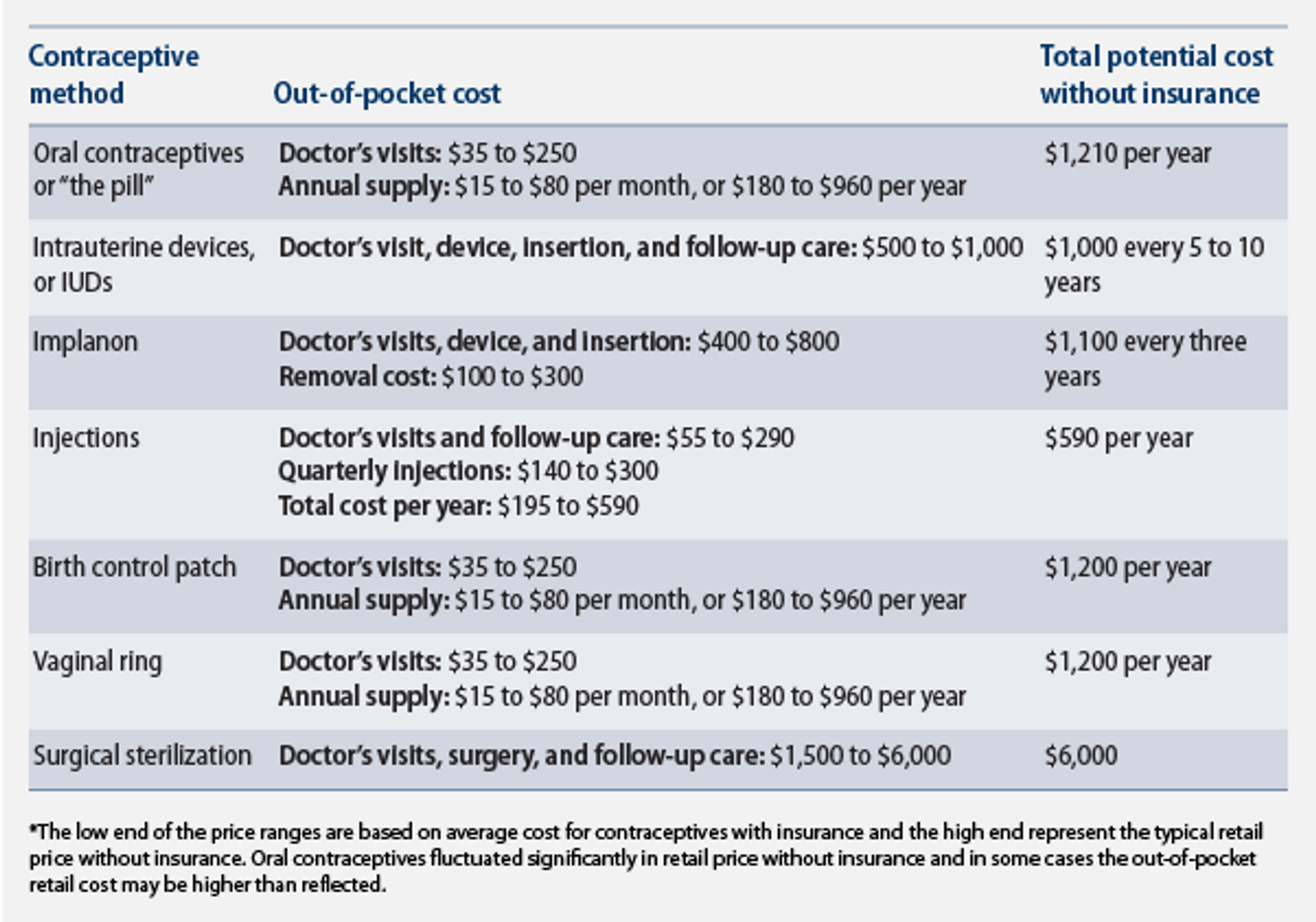

It’s a common misconception that birth control is easy to come by and affordable to buy. It is, in fact, quite expensive — especially for those without health insurance. In 2012, the Center for American Progress found that for uninsured Americans, the potential annual cost of oral contraceptives alone is $1,210, an impossibly large sum for many people.

The economic burden of these costs contributes to inconsistent and discontinued use of contraceptives among low-income women. In a study by the Guttmacher Institute of women aged 18–34 with household incomes below $75,000, found that cost led many women to cut corners with their birth control, skipping pills, delaying prescriptions, or adopting a one-month-on, one-month-off approach to taking the pill. One in four women who struggle financially are forced to take such measures; among women with financial stability, the rate is roughly one in seventeen.

Beyond inconsistent oral contraceptive use, low-income women are less likely to access the most effective forms of birth control. Hormonal implants and intrauterine devices (IUDs) have success rates of 99 percent in preventing pregnancy — far more effective than birth control pills or condoms. These long-acting, reversible methods need zero maintenance, taking human error out of the equation while lasting between three and ten years. But the frontloaded cost of these methods restricts their availability to women with low incomes; the most effective forms of birth control are used mostly by affluent women.

Why Title X Matters

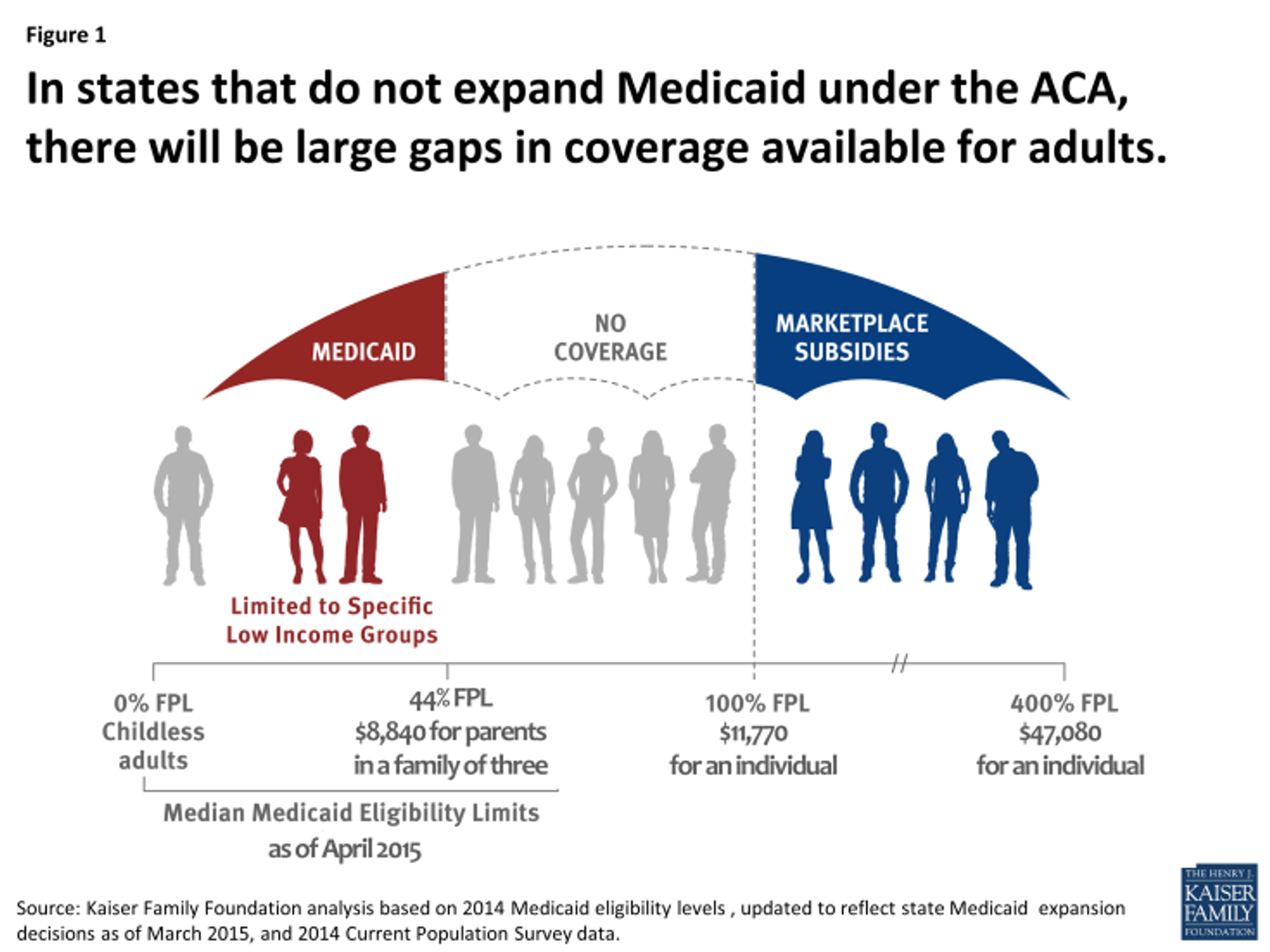

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) intended to expand healthcare insurance to almost all Americans, regardless of their income. To do this, the ACA expanded Medicaid to fill in historical gaps in healthcare coverage, covering all individuals with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty line (previously, Medicaid was only available to families making less than 44 percent of the poverty line). After a Supreme Court ruling in June 2012, the proposed expansion became a state-by-state choice. Twenty-one states opted not to expand Medicaid, creating a coverage gap for families whose incomes are too high for Medicaid coverage, but who are still not wealthy enough to be eligible for a subsidy. Nationally, almost 4 million adults fall into this gap. Women in the coverage gap are left without insurance, and as such, are forced to bear the oftentimes-unattainable costs of birth control, affording them little agency in their reproductive decisions.

Where the government and market leave coverage gaps, women’s health clinics often pick up the slack. Planned Parenthood, for instance, primarily serves low-income women — 75 percent of their clients make less than 150 percent of the poverty line. Federal budget cuts to Title X Family Planning, along with state budgetary proposals to cut funding for Planned Parenthood, have caused systematic closures of clinics across the country. If passed, the budget cuts being considered by Congress would further break apart this cracking funding system.

We’ve seen it already. Texas, the state that enacted the nation’s largest budget cuts to family planning organizations, forced the closure of 25 percent of Planned Parenthood clinics in Texas. As a result, clinics were only able serve 54 percent of the clients that they had prior to the cuts. Long-acting, reversible contraception methods, initially offered at 71 percent of clinic sites, became significantly less accessible, available at only 46 percent of them. A recent study by the Texas Policy Evaluation Project surveyed 300 pregnant women who sought an abortion in Texas. Approximately half responded that they were “unable to access the birth control” in the three months before they became pregnant.

In all the talk of budgets, poverty lines, percentages, and politics, it’s easy to forget that the issue is, at its core, about people. Policy is, by its nature, abstract, but the people it affects are real. Unless Medicaid access is expanded and Title X Family Planning funds remain available, life will get worse for many women, the cycle of poverty will continue, and the underlying issues will linger on without a hope of being solved.

* * *

Miriam Kelberg is a contributor to the Wilson Quarterly.

Photo courtesy of Planned Parenthood