Spring 2015

Science, Meet Journalism. You Two Should Talk.

– Louise Lief

Science and the media need each other. They just don't know it yet.

When I began my term as a public policy scholar at the Wilson Center last year working on the project “Science and the Media,” I ran into a journalist colleague I hadn’t seen in years. When he heard what I was doing, he said in astonishment, “Science? How did you get interested in that?”

He wasn’t the only one to react that way. It’s a symptom of the relationship — or more precisely, the lack of a relationship — between scientists and the vast majority of journalists who do not cover science that such an interest is seen as unusual.

Not only journalists view science in this way. Many in the public do too. To the majority of Americans, science is a foreign country.

I don’t have a science background, and developed an interest in the sciences through a somewhat roundabout route. Years of taking groups of editors on fact-finding/study tours to Africa, Latin America, Asia and elsewhere introduced me to landscapes and creatures in the natural world of astonishing beauty and variety, and the fascinating professionals who often took insane risks to study them, seeking to understand how things worked and why.

So for my project I decided to concentrate on the general media — the 90 percent who almost never meet scientists or write about science, and to focus on the natural world. I wanted to see what the barriers were to engagement, and to explore how these two groups might begin a conversation, and maybe even work together in mutually beneficial ways.

In the process, I discovered how much these two communities have to offer each other, far beyond the subject matter.

The Gap Between Scientists, the Public, and the Media

To many Americans, scientists are strangers in our midst.

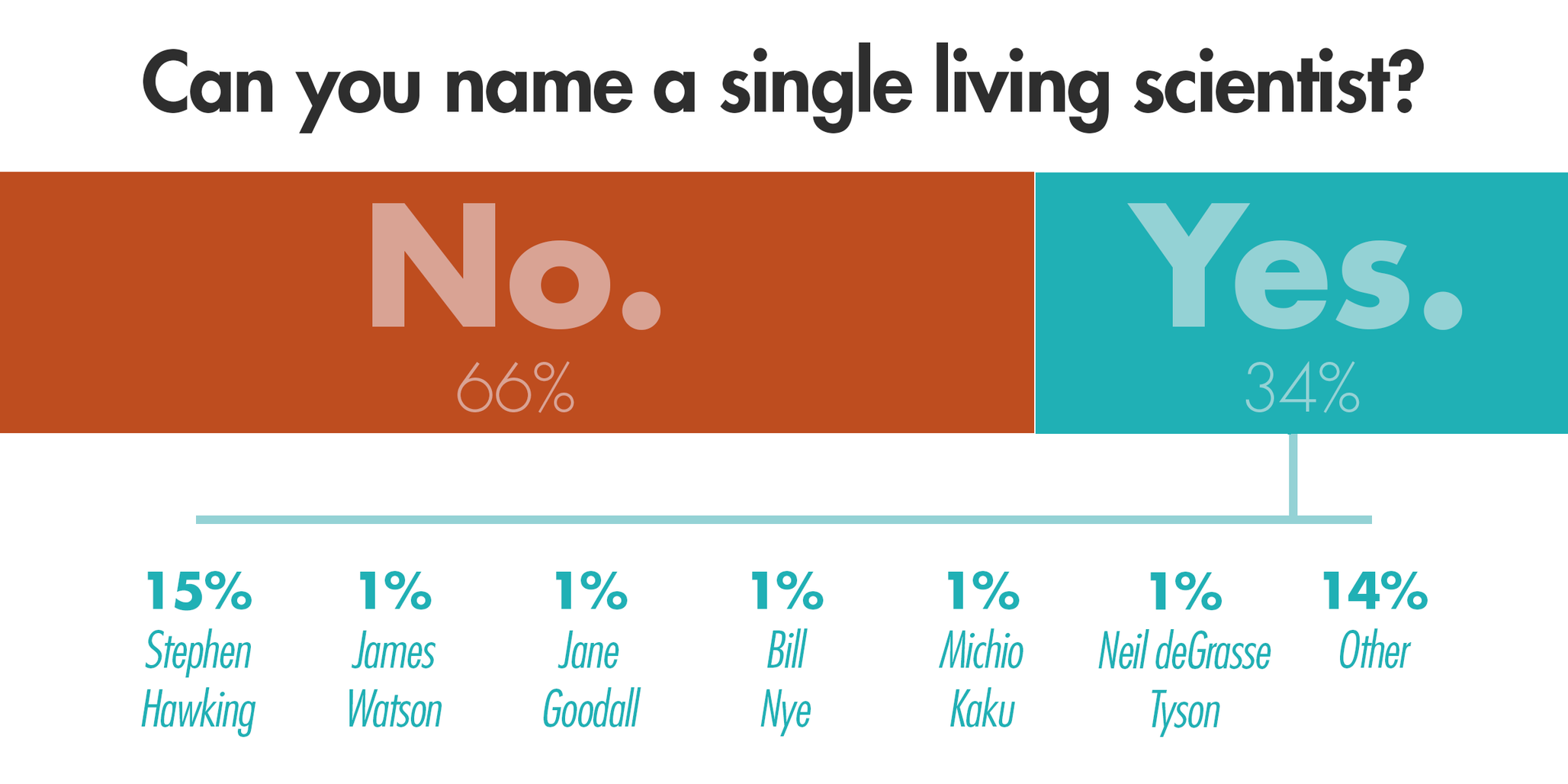

In a March 2011 Research!America survey, two-thirds of Americans polled could not name a single living scientist. Little surprise, then, that the National Science Board has found that a majority of Americans do not understand what scientists do at work.

Undoubtedly, this contributes to the wide gap that exists between what scientists think and what the public believes. According to a 2009 Pew Research Center poll, while 87 percent of scientists accepted that natural selection plays a role in evolution, only 32 percent of the public agreed — one of the lowest percentages in the developed world. And in May 2013, the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication found that while 97 percent of scientists believed human activities cause climate change, only 41 percent of the U.S. public concurred.

In the general media, where most of the public still gets its news, there is almost no science or environmental coverage. A Pew Research Center content analysis of a broad sampling of media outlets cited by the National Science Board revealed that from 2007 to 2010, science and technology accounted for only 1.5 percent of all news stories, with the same percentage for environmental news. That number dropped to one percent in both categories in 2011.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are 58,500 reporters, correspondents and broadcast news analysts in the U.S. While there is no specific tally of science and environmental reporters, the combined memberships of Society of Environmental Journalists, National Association of Science Writers and Association of Health Care Journalists are around 5,000, a figure that includes many non-journalist members.

Many news organizations have no science or environmental reporters. They are considered unaffordable luxuries. Even those that have them have greatly reduced their numbers, often to one person. Journalists reporting on other areas seldom consider these disciplines in relation to issues they cover.

The sense that science inhabits a separate box also affects media coverage and placement decisions. During a panel at the recent Online News Association conference in Chicago, one of the nation’s largest annual journalism gatherings, Wolfgang Blau, The Guardian’s digital strategy director and an astute media observer, wondered aloud about how the media’s coverage of climate change, one of the greatest challenges of our time, has become “at best, a subsection of the science section.”

Removing Barriers

I have often heard scientists state that the general media aren’t interested in science. I wanted to test that hypothesis.

I approached two major scientific institutions, New York’s American Museum of Natural History, and Washington D.C.’s Smithsonian Institution, and proposed that each do a professional development pilot program designed for journalists who do not cover science to try new approaches for this media community, and get their feedback.

To their credit, both institutions were eager to participate, keen to interact with the journalists they seldom see. Both programs focused on exploring the natural world, and combined science content with a journalism “craft” or skills component.

The AMNH program, which took place on June 18, 2014, a Wednesday night, was called “Hidden Light: Exploring Oceans for Creatures that Glow.” The science content was bioluminescent and biofluorescent marine animals, creatures that produce their own light. The journalism craft component was underwater photography, which scientists use to record the dazzling multicolored flashing displays that take place in the ocean at night, often at great depths.

After a short presentation by AMNH ichthyology curator John Sparks, journalists participated in a hands-on “obstacle course” constructed by AMNH staff to simulate a variety of challenges scientists encounter trying to detect and film these glowing creatures underwater under dim, blue light conditions. Journalists also took a behind-the-scenes tour of the museum’s fish collections, which included seeing and touching a giant coelacanth, a fish thought to have become extinct with the dinosaurs.

The Smithsonian program “Right Fish, Wrong Place: Invaders in the Coastal Zone” looked at invasive marine species in the Chesapeake Bay region, particularly the blue catfish, and efforts to manage them. It took place on Saturday, September 6, 2014, at the Smithsonian’s Environmental Research Center (SERC) in Edgewater, Maryland, 40 miles east of Washington, D.C.

As part of the program, journalists canoed to the center of the Rhode River, where Smithsonian scientist Matt Ogburn demonstrated how scientists track thousands of fish with acoustic telemetry, the same technology used last March in an effort to find the missing Malaysian airliner. Greg Ruiz, head of SERC’s Marine Invasive Species Research Lab, had journalists search live crabs for “Alien” type barnacles that colonize them. His lab monitors all commercial shipping arriving in U.S. ports for invasive stowaways.

The journalism “craft” component was audience engagement, a hot topic in today’s newsrooms. Technology expert Robert Costello and research ecologist William McShea, who lead the Smithsonian’s eMammal citizen science team, demonstrated how they worked with volunteers to place remote sensing camera traps along the Appalachian trail and throughout the mid-Atlantic region to document the impact of hiking and hunting on wild animal populations. They discussed the IT infrastructure they built to organize the millions of images the project generated, and the viral public response to images that were posted. They are gearing up for a new project to chart the movements of carnivores in 20 cities across the United States in collaboration with numerous local partners. They hope to scale up from a repository of 4 million images to 30 million images that any middle schooler can access with the push of a button.

Lastly, James Beard Award-winning chef and restaurant owner Jeffrey Buben prepared blue catfish several ways for lunch, while regional seafood distributor Tim Sughrue, a representative from Whole Foods Market, and the chief of inland fisheries from Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources discussed regulations and certifications in the seafood industry, and the rapidly expanding commercial market for blue catfish.

Both programs shared several key features. They emphasized experiential and hands-on approaches. They combined science content with a journalism craft component. Anyone in the newsroom with an interest could come, up to three members per news organization. Participation was voluntary and after work for both scientists and journalists.

Fifty-three journalists from 33 national, international, and regional news organizations and journalism school faculty participated in the two pilot programs. Their ranks included White House correspondents, foreign correspondents, general assignment reporters, video journalists, radio and television producers, political, defense, security, foreign affairs, cultural and congressional reporters, editors, editorial writers, news directors, digital and multimedia reporters, and local TV news. Only a few covered science. Most had never visited the host institutions or hadn’t been there in many years.

Though the primary goal of the programs was engagement, some of the journalists produced (or are currently working on) stories. The Associated Press video below is one, and combines several elements from the Smithsonian pilot program. The journalist said that not only was the story fun to do, it also gave her an opportunity to experiment with several new technologies — a drone for aerial shots, and underwater photography to film the fish.

The journalists’ feedback on the programs was overwhelmingly positive, and many asked for more such opportunities. Several journalists wanted to stay after the lengthy Smithsonian program to brainstorm with their colleagues on various ways to use the material. Others contacted me afterwards to suggest topics for future programs.

Most of the AMNH participants also filled out a survey asking an open question about which areas in the sciences interest them. They listed 34 topics across a broad range of subjects — everything from geology to brain science to time travel.

These findings raise an obvious question: If there is so much interest, why is there so little science in the general media?

Part of the explanation lies in a lack of access and opportunity, and the current newsroom structure.

There are few organized opportunities for working media covering other topics to learn about the sciences. Non-science journalists may not see the relevance, have editors who aren’t interested, or feel they don’t have enough expertise to write science stories or include a scientific dimension in their articles.

In some newsrooms, non-science journalists are not allowed to do science stories. Though every news organization needs specialists, I worry that this approach to such a vast field of knowledge sends the all-too-familiar message that science is so specialized and complex that journalists (you can also substitute “the public” here) without science backgrounds couldn’t possibly understand it. In a revealing choice of words, many journalists at the AMNH pilot program referred to themselves as the “lay media.”

Don’t misunderstand: I love science journalism and wish there were more of it. I serve on the board of the D.C. Science Writers’ Association, which endeavors to create more professional opportunities for science writers, who face their own set of challenges. But if the only place an audience can find science is in the ‘science box’ — if it’s not connected to other areas and issues — it’s easy to ignore.

Access means not only the opportunity to speak with scientists. It also signifies having productive interactions with them. Most non-science journalists want experiences and adventures in language they can understand, and — as many of the journalists commented approvingly in their program evaluations — no preaching. Finally, connecting the science to outside actors like the seafood distributor and chef helped generate story ideas.

Where Science and Journalism Come Together

For more than a decade now, news organizations have seen their advertising revenues, subscriber bases, and company values shrink. The public’s relationship to news and information has changed. People now consume news on a variety of devices in different formats. Social media has upended traditional media models.

Many news organizations struggle to remain profitable while they produce multimedia reports, blog, tweet and post to multiple social media platforms on a 24/7 news cycle.

Out of the turmoil, new forms of journalism are beginning to emerge. Startups are experimenting with unconventional ways to present information and engage audiences, sometimes even before a story appears. Traditional news organizations are adopting many of these strategies, too; they must innovate or risk falling behind.

The word “audience” has taken on new meanings. More news organizations now focus on creating communities of valued, active participants who engage with the organization in a variety of ways and through shared experiences. As staffing reaches critically low levels, newsrooms are also scrutinizing their “beat” structure.

The Rise of Hacker, Data, and Sensor Journalism

In traditional newsrooms, journalists may never meet developers, coverage can become siloed, and reporters compete more often than they collaborate.

The new digital news startups seek to foster what they call a “hacker culture.” In other words, they experiment. Interdisciplinary teams of reporters, designers and developers work side by side, trying different formats and new ways to deliver information. They hold internal “hack days” to play with new ideas.

The new “hacker journalists,” writes Maryanne Reed, West Virginia University’s journalism dean, seek to transform digital storytelling by visualizing and mapping data, building open-source news apps, and focusing on what they call “responsive design” and audience engagement.

Melissa Bell, co-founder of Vox.com, a new site that specializes in explanatory journalism, and Vox developer Yuri Victor, spoke recently at American University about the Vox.com model. Their mantra, says Bell, is “Launch, listen, measure, improve.” They see how users respond to information and what reporters want to do with it, and then build digital tools to suit, learning as they go. Since Vox.com launched in April 2014, their audience has grown to more than 22 million unique visitors a month.

“Data journalists” mine the massive amounts of data now available from a variety of sources for hidden stories, looking — as scientists do — for patterns and anomalies. According to Alexander Howard, author of a report on data journalism for Columbia University’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism, they gather, clean, organize, analyze, and visualize it, “interviewing” it like a human source to verify information and add context, harnessing it to “support the creation of acts of journalism.”

Many of the digital tools journalists and the public now use were originally developed by scientists to perform research tasks.

Both hacker and data journalists focus intently on audience interaction. NPR visuals editor Brian Boyer writes on his blog hackerjournalist.net, “Our success is measured in engagement, not views.”

Many of the digital tools journalists and the public now use were originally developed by scientists to perform research tasks. Another of these tools is now in the journalism pipeline, in the new field of “sensor journalism.”

Journalists are beginning to explore the potential of using sensors to create data and news stories. Matthew Waite, principal developer of the Tampa Bay Times’ Pulitzer Prize-winning political fact-checking website PolitiFact and founder of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Drone Journalism Lab, is experimenting and building prototypes. He is but one example of the new hybrid journalist/developer that is changing journalism.

The Rise of Citizen Science

On a parallel track, many scientists and government agencies now find that enlisting the public to assist in gathering information can help them answer questions too large or expensive for a single research team to handle. They are turning to crowdsourcing and citizen science to collect the data they need and, like hacker journalists, they build the tools as they go.

Hundreds of these projects use mobile apps for activities like identifying insects, plants and trees, groundtruthing weather, and detecting earthquakes. Scientists give small palm-sized sensors to the public to measure noise, light, air, and water pollution.

Some projects involve hundreds of thousands of people collecting and classifying millions of pieces of data. Scientists have had great success developing algorithms and other software tools to assure data quality equivalent to (and sometimes exceeding) traditional scientific research.

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy is encouraging federal agencies to engage the public through citizen science and create “citizen solvers.” A growing number of federal agencies have launched citizen science and crowdsourcing initiatives, and 20 federal agencies participate in a working group to develop common standards and open innovation toolkits.

A new Citizen Science Association just established several months ago will meet for the first time in February 2015 in San Jose, California, to discuss innovations in their field. A description of a panel they are hosting at the annual American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting sounds like one you might find at a journalism conference. They are experimenting with image analysis, gaming, large-scale data collection, visualizations, and new ways of gathering information, connecting communities, and engaging the public.

How might the new tools and techniques citizen science practitioners are developing benefit journalism and the public? Where does the media fit in this picture? Shouldn’t these two be talking?

Beyond citizen science, mixing more often yields other benefits for both journalists and scientists. The process of scientific discovery holds useful lessons for today’s newsrooms. Scientists investigate, collaborate, problem solve, experiment with new approaches, build tools and verify data. They deal with setbacks. Observing these processes, even in a different discipline, will help journalists in the changing newsroom where they will need all these skills.

By interacting more frequently with different kinds of journalists, scientists will gain a better understanding of how a diverse public regards their work. Business, culture, and religion reporters often ask very different questions from the ones science journalists ask. Their questions are important. Seeing how the media presents information and engages with audiences also offers invaluable lessons for science.

A model for productive exchanges between scientists and communicators already exists in the entertainment industry.

The National Academies of Sciences, with the support of Hollywood producers Jerry and Janet Zucker, established the Science and Entertainment Exchange in 2008. Directors, producers and screenwriters participating in their programs meet scientists, learn about different scientific fields, and brainstorm on possible projects. Barbara Kline-Pope, the Executive Director for Communications for the National Academies who helped establish the Exchange, describes the organization’s approach very simply: “When you put creative people together in a room, good things happen.”

These interactions have resulted in new characters and plot lines in film and television, and even new programming. The most famous example is the television series “Cosmos” on Fox. The series’ host, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, met Seth MacFarlane, creator of the hit TV series “Family Guy,” at a Science and Entertainment Exchange event. McFarlane, with his established business relationships in Hollywood, was instrumental in finding the “Cosmos” reboot a home at Fox, and went on to serve as executive producer for the series.

There are, alas, very few in-house professional development opportunities at news organizations. But that unmet need also presents an opportunity.

The following is a modest proposal to bridge the gap

For science institutions:

Once a year, host a media open house and invite anyone in the media interested in trying something new. Make it experiential and fun, and include a journalism skills component. Even an elaborate program can be done at very low cost. Don’t fret about stories. Focus on building relationships. Get to know the journalists and solicit their feedback. If something didn’t work, fix it.

For journalists:

Step outside your comfort zone, meet cool people, have fun with your colleagues and discover a new discipline for part of a day. Learn more about the world around you. Witness examples of thoughtful risk-taking and learn strategies for tackling complex challenges. See how it makes you think about the work you do or might like to do. It doesn’t matter if you don’t do a story. What’s important is that you are exploring.

For editors:

Encourage (but don’t require) your staff to attend these events. I will bet that the journalists eager to come — the ones with restless energy who seek out new challenges and push boundaries — are also the ones who will give you the best work. This exercise will give them new ideas, and help them flex the muscle groups they will need to innovate in the changing newsroom.

You can come too.

* * *

Louise Lief was a 2014 public policy scholar at the Wilson Center, affiliated with the Environmental Change and Security Program and the Science and Technology Innovation Program. She can be reached on Twitter at @sciandmedia or at llief@mediaandscience.org.

Visuals by Zack Stanton

Cover photo courtesy of Reuters/Kevork Djansezian

This story has been updated to correct the name of the Association of Health Care Journalists. An earlier version of this piece referred to the group as the Association of Health Reporters.