Fall 2007

Strive We Must

– Daniel Akst

Competition seems to be hard-wired into humans, but is that such a bad thing? A look at where competing has gotten us.

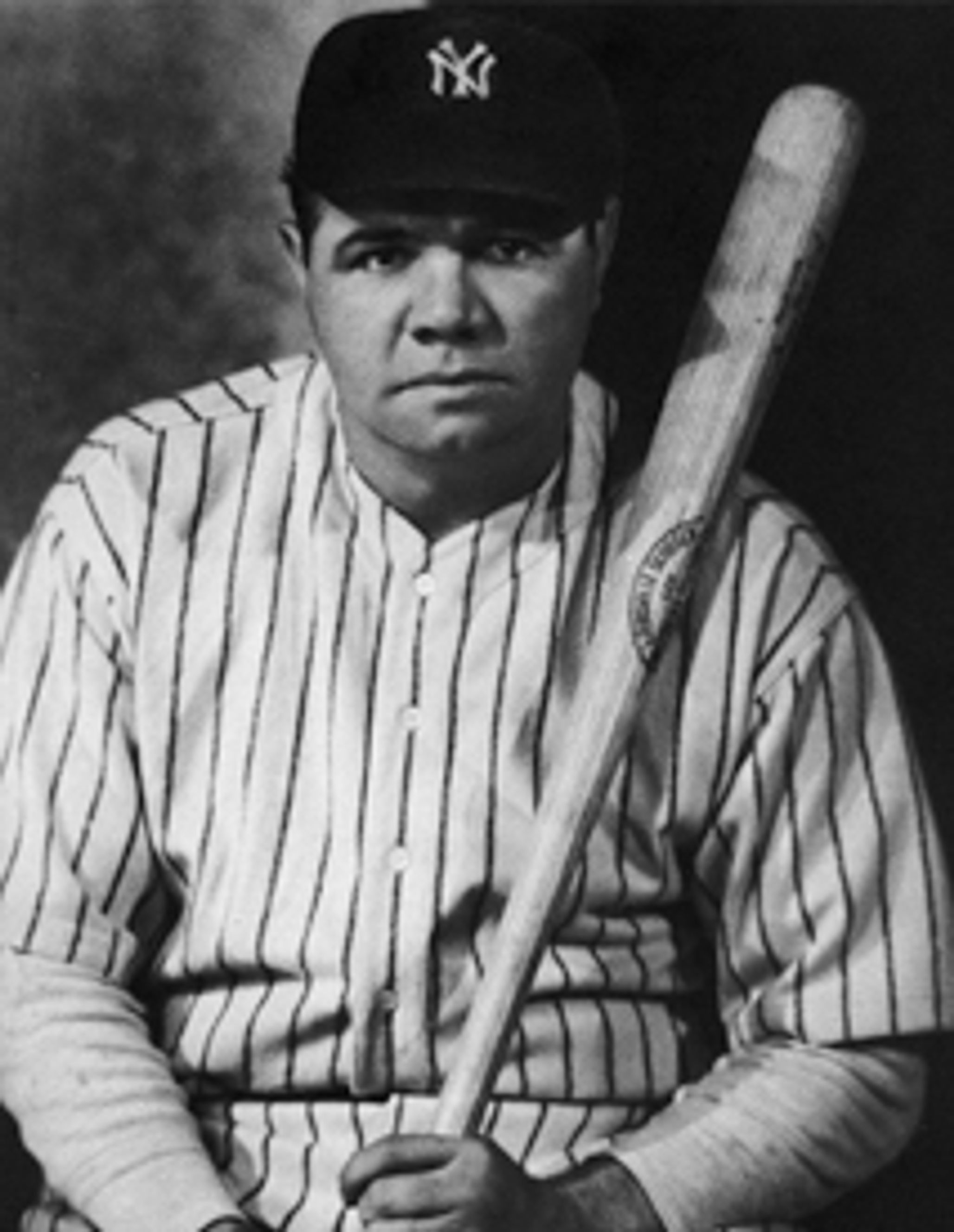

When the philosopher Satchel Paige warned us not to look back (because something might be gaining on us), he couldn't have imagined how prescient he was, even though his own career in baseball pointed the way to the world we would all someday inhabit. Restricted to the Negro Leagues for more than two decades, Paige finally broke into Major League Baseball in 1948. Within a couple of decades black ballplayers had become dominant figures in the majors, the Negro Leagues had collapsed—and baseball had become a much more competitive place.

That will happen when barriers fall. Technology has some of the same effects: Newspapers find themselves competing with bloggers, traditional stores with Amazon, and singles bars with Cupid.com. Americans find that, thanks in part to technologies they invented or pioneered, they’re competing with workers in India, China, and other far-off lands who are willing do the same work for a lot less money. Even individuals in need of a Little League logo or a personal webpage are finding people who can do the job for less in Bucharest or Bangladesh.

Competition—the reality but also the metaphor—has somehow come to pervade modern life, much as we try to wish it away or pretend, as in five-year-olds’ soccer games, that it isn't really going on. In some cities, the preschool admissions process is as fraught as the mass version of musical chairs with which top universities fill their classes. Stepped-up competition is apparent in the workplace as well. Companies are less willing or able to carry unproductive employees, but in today’s competitive business environment even productive workers can receive a pink slip when circumstances persuade executives that cutbacks make sense. Companies these days are less constrained by sentiment or tradition when considering whether to outsource, move, or shut a plant. A study earlier this year by economists Thomas Lemieux, W. Bentley MacLeod, and Daniel Parent found that “the overall incidence of performance-pay jobs has increased from a little more than 30 percent in the late 1970s to more than 40 percent in the 1990s.” Bonus, commission, piecework—whatever you want to call it, pay for production makes work seem a lot more competitive. When Fortune magazine reported on white-collar workers “fired at fifty” who couldn't find comparable positions, the best advice from the experts was to embrace “involuntary entrepreneurship,” which of course means competing on your own without a company-provided pension, health insurance, sick days, or vacation.

Globalization has spurred many changes. Firms that once shuffled along in cozy domestic oligopolies now find themselves battling overseas competitors. Deregulation of airlines and utilities, the dismantling of trade barriers, growing Third World productive capacity, rapidly evolving technologies, the weakening of restrictions that kept banks pent up within states and out of the securities business—these developments and so many others have helped foster a vastly more competitive commercial environment than existed a generation ago, an era well within living memory for many American workers, who recall a time when U.S. industrial might was unchallenged.

Even the home, ostensible refuge from worry and trial, has become a competitive arena. The overturning of traditional roles has meant that spouses may find themselves vying not just to see who can get out of doing the laundry, but for power, status, and renown as well. Consider the case of Ségolène Royal and her partner, François Holland, both ambitious French politicians and rivals for the same party’s presidential nomination. Surely, electoral jockeying made for some frosty breakfasts around their house (and in fact the couple recently parted ways). As for the rest of us, competition for filial affection has radically increased in many families thanks to the increased prevalence of divorce, in which parents sharing custody may find themselves in an authority-eroding contest for the favor of offspring who all too easily play one off against the other.

How did we get here? As is so often the case in American life, we’re victims of our own success. Despite a remarkable amount of hand-wringing, given the circumstances, life in this country for most of us is better than it has ever been—longer, fairer, freer, and richer. And that’s what makes for so much competition. More of us than ever before consider that we have a reasonable shot at an Ivy League education, a beachfront property, or a partnership in a law firm. The same is true for less glittering prizes. Discrimination persists, of course, but there’s less of it. Newspaper help-wanted ads no longer specify gender or faith, and real estate ads (to say nothing of deeds) have dropped their restrictions as well. In the political arena everyone’s got a lobby, it sometimes seems, except the country at large, and the old, nowadays more numerous and healthier than in the past, compete all too effectively for resources against the young.

Another factor in the seeming competitiveness of modern life is the astonishing efficiency of modern markets, as well as the acceptance of markets as the prevailing metaphor for so much human activity. In the public realm such one-time monopolies as the Postal Service, the local public school, and the regional electric utility, now have to compete against (respectively) UPS and FedEx, charter and magnet schools, and alternative providers of electricity, with whom consumers can contract. Market participants—that’s us—have better information than in the past as a result of the ratings, rankings, and reviews that are cropping up everywhere. Users report their experience with products on websites such as Amazon and Epinions; professors and schoolteachers are bluntly rated on sites such as RateMyProfessors.com (which covers sexual appeal as well as pedagogy); and publications including Consumer Reports, U.S. News & World Report, and various city magazines rate and rank for a living, so that sooner or later someone is likely to be anointed best dermatologist—or, for that matter, plumber—in Cleveland.

The irony is that it was competition, in the first place, that helped bring about the richer, fairer, freer—and intensely more competitive—society we have become. All the key forces at work—social change, technology, and globalization—are as plain as day on the baseball diamond. Time was, a young white fellow with a live arm, honed perhaps in sandlot games or by throwing against the barn wall, was competing only against others like himself. Today he’s competing against the best the world has to offer. Not only is the sport open to blacks and other minorities from this country, but a significant proportion of today’s players are foreign born. Besides the Latin Americans now so common in the big leagues, Korean and Japanese ballplayers are starting to turn up. (Professional basketball and hockey also draw on an increasingly global talent pool.) Foreign squads have been beating American teams in the Olympics and other international competitions for a while now, not just in baseball but in basketball as well. Free agency, meanwhile, has forced baseball team owners to compete for players, bidding up salaries so that now even a journeyman reliever earns a small fortune. Nor is milking cows any longer the primary builder of wrist strength. Just as travel and telecommunications technologies have made it possible to recruit more widely, advances in training, dietary science, and medicine have enabled players to hit the ball farther and throw it faster.

College admissions is another arena where competition has blossomed riotously. When I applied to college, back in the raccoon coat days of 1974, you had to complete a separate time-consuming application for each institution; Yale’s was so daunting that I didn't even bother. I applied to five or six schools and visited none. Despite only decent grades and a mediocre math showing on the SATs, I got into some excellent institutions, and attended one without hysteria, consultants, or prep courses. My graying friends and I agree that we wouldn't stand a chance of admission into our own alma maters today. Students are much more focused and accomplished, and the marginal cost of an additional application has plummeted; the rise of the “Common Application” (often filed electronically) has made it easier to apply to many more schools than I did, and high school students are doing just that.

My graying friends and I agree that we wouldn't stand a chance of admission into our own alma maters today.

About those spectacular students: You can expect to see more manufactured greatness in the years ahead, and even tougher competition in many arenas, now that genius looks more likely to be made than born, at least in the eyes of those who study such things. Chess prodigies are proliferating, for example, thanks to computer-based training methods, but in fact prodigies are proliferating in many different fields as a result of better training, determined parents, affluence, and, yes, tougher competition. “The standards denoting expertise grow ever more challenging,” Philip E. Ross wrote last year in Scientific American, where he was a contributing editor. “High school runners manage the four-minute mile; conservatory students play pieces once attempted only by virtuosi.” Ross reports on studies comparing tournament chess from 1911 to 1993 which found that modern players made far fewer errors, and that today’s top chess players generally are much better than the grandmasters of yore.

Circumstances and ideology these days are supporting all this competition. The collapse of communism almost everywhere (in China it lives on in name only, supported by something like a capitalist frenzy) has left one brand or another of the market economy as pretty much the only game in town. Pro-competition ideologues (and such intellectual forebears as Adam Smith and Milton Friedman) are in the ascendance, and economists generally have expanded their turf across almost the whole of human activity (including such highly competitive arenas as sex), sharpening our understanding of competition’s role in our lives. Evolutionary biology, perhaps the other preeminently influential academic discipline of our times, also has competition at its core. Our view of courtship nowadays is as likely to be influenced by Charles Darwin as Jane Austen, and thanks to online dating (the sexual equivalent of eBay?), the Internet gods are playing nearly as big a role as Cupid.

Competition has also been rescued to some extent from the class-based doghouse in which it dwelt for so long. In the bad old days, after all, trying too hard was considered poor form; success was supposed to come easily, like one’s wealth and position, and not require any of the sweaty striving associated with the lower orders. Those days are blessedly past—we are all sweaty strivers now—yet we remain ambivalent about this state of affairs. We feel nostalgia for the ethos of good form, and for the freedom from class anxiety we might have felt in a more static society. Who among us has not referred, at some point, to competitive modern life as a rat race? Which of us has not vowed, sooner or later, to foreswear it, presumably in favor of a return to our natural state of romping in the meadows with the butterflies? We want our kids to do well, yet competition is something we want to shelter them from. That’s why, in northern California, some high schools with large numbers of Asian-American students are experiencing white flight among families who find the academic environment a mite too . . . hectic.

For all their rhetoric, business executives don’t seem to like competition much either, and in this at least they frequently have unions on their side. Remember The Man in the White Suit (1951)? Alec Guinness plays a man who anticipates glory and riches for inventing an indestructible fabric, only to discover that labor and management are united in their fervor for his scalp. Executives and commentators have often complained of “cutthroat,” “murderous,” or “ruinous” competition. Many corporate mergers—such as the recent acquisition of Wild Oats Markets by Whole Foods Market—are initiated by executives who hope in part to make markets less competitive by joining one-time rivals. Even our own government is dubious; while antitrust laws exist to suppress anti-competitive practices, a host of other government initiatives—such as costly federal farm policies—work to suppress competition.

More than one liberal intellectual is ready to call a halt. In his book No Contest: The Case Against Competition (1986), Alfie Kohn urged us to embrace cooperation and get our kids to play non-competitive games. Some schools have taken this idea to heart by embracing a euphemistic grading system to avoid the nakedly hierarchical A through F that most of us old-timers remember (rest assured, the kids know very well that NI—“needs improvement”—is about the same as a C). David Callahan, in The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead (2004), answers his own implied question by blaming an excessively competitive society. In the realm of baseball, for instance, Callahan cites the case of an overage pitcher in the 2001 Little League World Series, who mowed down the younger kids until he was unmasked. Yet the evidence for competitively inspired corruption is anecdotal at best; back in the halcyon days of 1919, after all, the real World Series was tainted in the so-called Black Sox scandal, and in 1951 the New York Giants won the National League pennant thanks not just to Bobby Thomson’s game-ending Shot Heard ’Round the World but to the team’s premeditated theft of signs from opposing catchers.

Callahan is on firmer ground when he brings up the steroid allegations that have dogged slugger Barry Bonds. It’s still unclear how widespread doping has been in baseball, but if you watch a game or two from a mere 25 years ago on ESPN Classics, the change is striking: The earlier players seem downright Lilliputian by modern standards. Sadly, steroids are just another example of technology boosting performance in a competitive environment, and these phenomena are not limited to the majors. Nowadays the parents of some school-age players are pressing doctors for rehabilitative surgery on perfectly healthy young elbows, in hopes that the procedure will deliver a couple extra miles per hour on a high schooler’s fastball (fortunately, it can’t).

We may be doomed to earn our bread by the sweat of our brows, but before we plunge into despair over a dog-eat-dog society that grows more competitive by the day, it’s worth keeping a few things in mind about competition.

It used to be worse. Think of the Roman gladiators! Or in our own country, consider Oklahoma: After it was snatched from the Indians, the future state was apportioned by means of a land rush, with settlers trampling one another to get at prime spots. Nineteenth-century business practices were truly red in tooth and claw, while total output per person was so much lower in those days that merely staying alive was a competitive scramble for most people. Larger family sizes, meanwhile, meant more competition for parental attention, food, and inheritable resources.

Life is not as competitive as the media might have us believe. It’s important to remember that our cultural elites live with so much competitive anxiety that their lives simply aren't representative. Most Americans have more leisure than they did a generation ago, even as the highest-paid earners work like maniacs. And competition of all kinds is worst in places such as New York and Los Angeles, where real-estate hysteria and preschool panic afflict even the rich and powerful. The media come to us from these places, and are produced by people who live in a culture of frenzied attention grabbing that sooner or later disappoints everybody. Reports from these precincts should be discounted by at least 50 percent.

It’s our nature. This is probably not a great argument for anything, but it’s worth noting that competition is at least as natural to us as cooperation. Hierarchies crop up almost everywhere, in every setting. Remember Animal Farm? Everyone was equal, sure, but some were more equal than others. It’s the same in real life, where, in the words of psychologist David M. Buss, “conflict, competition, and manipulation also pervade human mating.” The desire to mate—and the imbalance between the most desirable partners and the many more people who covet them—“catapults people headlong into the arena of competition with members of their own sex,” even if they don’t always recognize that what they’re doing—angling for a promotion, applying eyeliner, cracking jokes—is competitive behavior.

Competition is—dare we admit it?—good for us. The desire to win was surely one of the things that motivated Branch Rickey to break baseball’s color barrier by bringing an African-American ballplayer to the Dodgers. In college admissions, competition is the handmaid of meritocracy, to say nothing of diversity. In the old days, places at Ivy League universities were bestowed like a birthright on graduates of the right prep schools, but nowadays spots are won as the result of a wide-open national and even international competition. Students are still constrained by circumstances, of course, and the affluent always have an edge, even when admissions are need-blind, just by virtue of their upbringing. Yet by any reasonable standard, the competition today is fairer as well as keener. At the same time, universities compete with one another for students and prestige, with the result being a remarkably varied and dynamic system of higher education that is the envy of the world—and a stark contrast with a relatively uncompetitive K–12 system that performs poorly by international standards.

In business, meanwhile, global competition has raised American living standards, helped lift giant swaths of Asia out of poverty, and knit the world much closer together. Competition even fosters cooperation. The whole basis of the company is that those within will work together to best those without, taking advantage of informational edges and other advantages to compete more effectively. And management specialists now emphasize the need for companies to forge more collaborative relationships with suppliers, customers, and even sometime rivals. The cooperative spirit reaches far beyond business. The world’s biggest champions of competitive individualism are also its biggest philanthropists. Charitable giving by Americans totals 2.2 percent of the gross domestic product, more than twice the share of wealth contributed by any other nation. Competition spurs accomplishment. How many fortunes have been amassed, home runs hit, novels penned, all because of competition for money, status, or mates? Surely, culture has gained right along with the gene pool as a result.

American universities compete for students and prestige, creating a system that is the envy of the world, and a stark contrast with our uncompetitive public schools.

The question, of course, is not whether to stamp out competition but how much to constrain it. It would be relatively easy to sand off the roughest edges of competitive modern society without altogether dulling its edge. Universal medical coverage and better K-12 education—preferably accomplished in both cases by exploiting rather than eliminating competition—would help not just the losers in competitive life, but the less victorious as well. Doping in baseball surely could be contained if owners and players shared the desire to do so; all it takes is for the fans to care more about cleaning up the sport than watching home runs. And the college admissions frenzy might be considerably eased if applications were rationed. High school students might be given 10 points, with each application costing at least one. Colleges could weigh an application’s seriousness by how many points were spent on it, just as early-decision applicants today often get an edge.

One problem is that constraining competition usually means giving up something. Keeping out Wal-Mart means paying higher prices. Erecting barriers to imports means a return to the poorly made clunkers Detroit turned out before Toyota scared the dickens out of everybody. De-emphasizing grades creates the risk of encouraging mediocrity.

Yet it seems inevitable that as income inequality grows, so too will pressure to further tax (in the broadest sense) the winners for the benefit, at the very least, of the somewhat less victorious. Meanwhile, it’s probably wise to keep the competitive cast of our culture in perspective. Like traffic, it’s often unpleasant, but it’s a sign of success in a community rather than failure. It’s the price of dynamism, of openness, meritocracy, and flexibility and even freedom. It was competition that gave us the modern world. For better or worse, the modern world appears determined to repay us in kind.

* * *

Daniel Akst, a recent public policy scholar at the Wilson Center, is a novelist and essayist living in New York's Hudson Valley.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons