Summer 2019

The Big Leak

– Danielle Neighbour

Water is the hidden imbalance in U.S./China trade. The stakes for the climate and the economy are high.

As you read this, you’re likely wearing some piece of clothing that is made in China. After all, over half of the world’s clothing is made in China.

The pervasiveness of clothing made in China in U.S. markets is certainly one of the things that comes to mind when talking about the balance of trade between the two nations.

But there is a hidden price tag on all the clothing that is made in China. It’s a considerable sum—and growing—that is skewing the trade relationship and putting its future at risk.

That hidden price tag is water.

Much like a carbon footprint, water consumption has a footprint. It comprises not only the water we use for drinking, laundry, and other daily uses, but also the hidden water in our products.

Clothing the world requires a lot of water: first to wash the cotton, then to manufacture it into a garment, and finally to dye and treat it. And the water required goes up when you factor in pollution: the chemical waste from this process is often dumped into rivers.

As China continues to make more clothing, its water supply faces a double whammy: first, by sacrificing thousands of liters of freshwater for the manufacturing, and then again by polluting its own rivers, many of which are now too contaminated for human contact.

This hidden water in products, often referred to as virtual water, plays a significant role in the global goods trade. Water is hidden in more than just textiles; it goes into everything we use, eat, and wear. Crops must be irrigated, fuel sources must be fracked, and materials must be processed with water.

As goods are shipped and traded around the world, the water used to make or grow them is therefore also traded. When significant changes in the trade status quo occur, so does a nation’s water imports or exports—and thus its overall water supply.

If China hopes to keep its place as the world’s clothier, it must do a better job of stewarding its own water.

A Shifting Balance

One unforeseen impact of the ongoing U.S.-China trade war is a shift in the way water is spent between the two nations.

In 2017, China was the United States’ largest trading partner. Before the imposition of tariffs, China exported many water-intensive products to the United States; China is the world’s largest exporter of hidden water, and the United States is the largest importer.

Yet as trade between the two nations has stymied, the “water balance” between both the United States and China has changed.

For example, China imported zero soybeans from the United States in November 2018. Compared to the same month last year, the 4.7 million tons China imported from the United States not only represent $1.8 billion of lost value for U.S. farmers, but also a net gain of 5.08 billion cubic meters of virtual water for China.

This new reality means that the U.S. and China must adjust their water budgets—or else risk shortages.

China’s per-capita available freshwater supply is one-quarter that of the U.S., making it especially at risk of a water shortage. China’s per-capita availability is 2,061.91 cubic meters, compared to the United States’ 8,844.32 cubic meters.

Yet despite the U.S.’s significantly larger water resources, it is China that is leaking water in the current trade regime. China exported a net 2.4 billion tons of virtual water to the United States in 2012—enough water to support 6.3 million households for a year.

If China hopes to keep its place as the world’s clothier, it must do a better job of stewarding its own water.

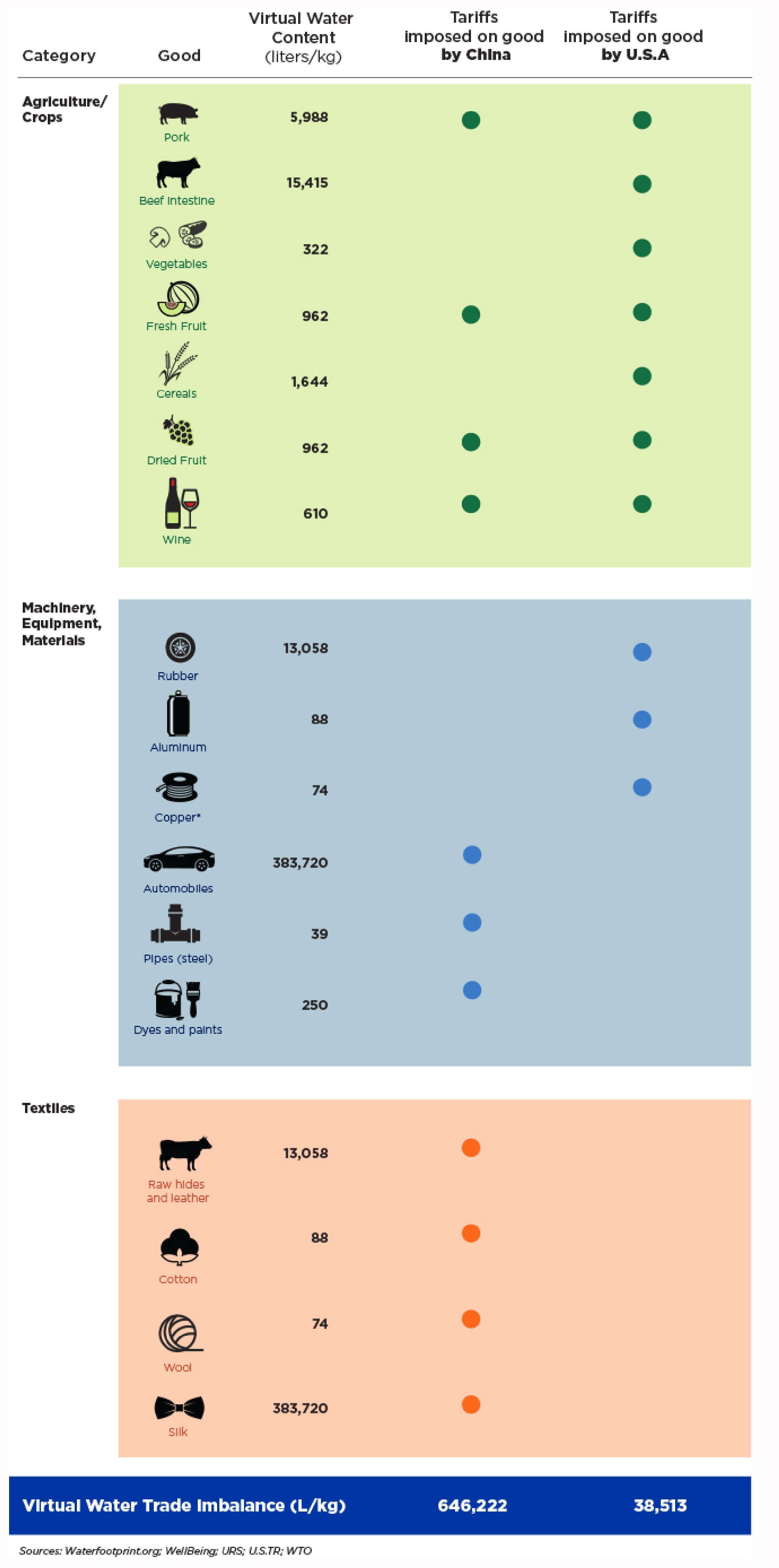

Nearly half (46 percent) of this imbalance is accounted for by water used to manufacture general machinery and equipment in China, which is then shipped to the United States. Another 19 percent comes from textiles, and agriculture accounts for the next largest portion (in fact, farming accounts for 65 percent of all water used in China).

Clothing, machinery, and crops are by far the most water-intensive goods traded between the United States and China. And as trade of these now-tariffed goods has slowed, the water balance between the U.S. and China has changed.

Both countries have tariffed many goods that are included in the three most water intensive trade industries. When you examine a list of tariffed goods from these three industries and their virtual water content (in liters per kilogram), the clear difference in the virtual water that’s been tariffed by each country is readily apparent: China’s tariffed goods in these categories have approximately double the virtual water content of goods tariffed by the United States.

And the virtual water trade imbalance is increasing. Because tariffed goods are traded less, these figures indicate that China is now receiving comparatively even less virtual water from the United States.

Since the trade war began in July 2018, the United States has actually imported more Chinese goods in fall 2018 than it did the year before.

Exports of goods to China by the U.S. decreased by an average of 18 percent in a comparison of monthly trade from August, September, and October 2017 (before the trade war) to the same months in 2018, after tariffs were implemented. However, U.S. imports of Chinese goods—and therefore, Chinese water—increased by 7 percent in the same time frame.

Surprisingly, the total trade imbalance of goods at the end of 2018 increased by 17 percent since the beginning of the trade war—a 10-year high. Such an imbalance poses a water security risk for China.

With the U.S. again increasing its tariffs in May 2019 from 10 percent to 25 percent on $200 billion of Chinese goods—and China retaliating with another $60 billion in tariffs—the trade war’s impact on water continues to evolve. As China exports even more goods to the United States, and receives fewer in return, the water imbalance between the two nations will grow even more disparate.

Righting the Balance

What would a continuing—and expanding—virtual water imbalance mean? If left unchecked, it could cause water shortages in China that will be felt worldwide.

For example, China’s textiles sector uses up to 40,000 liters of water per kilogram of textile, but also creates 600 liters of wastewater per kilogram. Unfortunately, efforts to make the process more water-efficient have been difficult.

“In the eyes of many textile mills, there is a tradeoff between investing in water efficiency measures and investing in business growth,” says Kurt Kipka, the Vice President of the Apparel Impact Institute (Aii). The institute is currently working to show mills that this is a false dichotomy—saving water often does save money.

Textile mills are also shortening their own lifespan by polluting the water they rely on. Compliance with water pollution laws has been fraught in China: while wastewater discharge standards are in place, mills’ capacity to meet these standards is low. According to Kipka, both better training and an increased spotlight on these issues are necessary to close this implementation gap.

Employing over 10 million workers, the future of China’s textile industry is uncertain unless its virtual water use and pollution are properly managed. Kipka says doing so will require capacity building and training—both in textiles and across China’s other water-intensive sectors.

And while China must change its water management strategy, it is not the only nation with something at stake in the effort. Because of the U.S.’s reliance on Chinese imports, a water-poor China would put food security in the United States at risk. It could also cause shortages in the manufacturing, textile, and tech industries—even in cases where the U.S. doesn’t directly receive products from China. China’s role as the world’s top trader means shortages would affect the world over.

As hope for more negotiations arises after Trump and Xi’s June G20 meeting, the United States and China should take the world’s most precious resource into consideration as they negotiate. When China sends increasingly more of its water abroad in the form of exports, the country’s ability to manufacture goods is put at risk. And without considering the impact of virtual water in traded goods, the United States and China risk endangering the very export-oriented industries that rely on an ample water supply.

Danielle Neighbour is a Schwarzman Fellow at the Wilson Center’s Kissinger Institute and China Environment Forum, where she researches wastewater treatment, water recycling and environmental policy in the United States and China. You can follow her on twitter at @dgneighbour.

Cover image: Magazines trumpeting the trade war between the United States and China on a newsstand in Hong Kong. AP Photo/Andy Wong