Winter 2015

The Last Nazi Hunter

– Rebecca White

In the eleventh hour, German prosecution laws have altered the way Holocaust-era war criminals are prosecuted. But is it too late for justice?

It has been five years since Efraim Zuroff’s book was first published in 2009. Ostensibly a memoir of the now 66-year-old Brooklynite’s work as a self-proclaimed Nazi Hunter, “Operation Last Chance” is but one of many personal accounts of the Holocaust and World War II that line a set of musty-smelling shelves inside the Strand bookstore in Manhattan, where I picked up an $8 copy at Zuroff’s repeated (yet playful) urging.

“This is going to sound self-serving,” Zuroff had told me on a muffled line from Israel. His voice was raised to compensate: “You should really read my book!”

Zuroff works as the Director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Israel office and worldwide coordinator of its Nazi war crimes research division. He’s a proud successor to Simon Wiesenthal — the Center’s namesake and the original Nazi Hunter — and has dedicated his life to carrying Wiesenthal’s torch: finding Nazi criminals in hiding, exposing them, and bringing them to justice.

It was shocking to Zuroff, then, when just three years after he published his definitive history of Nazi hunting, a 2011 court case in Germany changed the very nature of the practice. As a result, almost 70 years after the end of World War Two, a mad rush to reap the benefits of this change is occurring on a global scale before the dwindling population of sentient offenders tapers to extinction.

IT ALL STARTED WITH A MAN NAMED JOHN DEMJANJUK, a retired Ohio autoworker. Demjanjuk was deported from the United States in 2009 and convicted in 2011 by a German court on 28,060 counts of accessory to murder for his role at the Sobibor death camp in Occupied Poland in 1943. Ninety-one years old at the time of the trial, Demjanjuk wasn’t prosecuted for a direct act of murder; he was prosecuted for accessory to murder simply for standing guard at the camp.

A new precedent was set. Prior to the Demjanjuk conviction, a charge of murder or accessory to murder could not be justified unless the courts could prove that a person committed a specific crime. “They changed the legal strategy,” says Zuroff of the case. “If you served in the death camps, you are automatically guilty.”

Ultimately, despite his conviction, Demjanjuk did not serve any of his sentence, as he died in March 2012 before his final appeal was heard by the courts (as such, under German law, he is technically still presumed innocent).

Such anticlimactic outcomes are the norm in Zuroff’s line of work. “I’m one-third detective, one-third historian, and one-third political lobbyist,” he says.

Finding the offenders is not always the hard part, and Zuroff’s frustration with legal recourse is heavily detailed in his book. Tales abound of known Nazi commanders who have evaded prison time, slipped through the cracks of justice, maneuvered their way through legal loopholes, crossed borders, feigned illnesses, and of course, denied, denied, denied.

“You have to understand,” is how Zuroff begins many of his sentences, before brandishing, humbly, his near encyclopedic knowledge of the intricacies involved in finding, catching, and successfully capturing, as he puts it, “anyone who in the service of Nazi Germany or its allies was actively involved in the persecution and/or murder of innocent civilians.”

This is Zuroff’s working definition of a Nazi war criminal, and to date, he claims he has found close to 3,000 Nazi criminals who emigrated to the West, although he says “quite a few were dead when I found them.”

Success is hard to measure given that countries can’t and don’t prosecute Nazis the same way across the board. In the United States, Nazi war criminals can only be prosecuted on immigration and naturalization violations, because their crimes were not committed on U.S. soil; murder and accessory to murder charges come if the alleged criminal is extradited back to Germany, and vary based on whether the suspect worked at a concentration camp or at one of the six death camps.

“This is crazy. I spent my entire professional life hunting Nazis, and I started 35 years after the war was over,” says Zuroff, who claims he has had a hand in getting legal action taken against close to three dozen Nazi war criminals. He does not consider this nearly enough, given the likelihood that an estimated 98 percent of the people who committed these crimes are already dead. “I lost a lot,” continues Zuroff. “I’m jealous of people like Wiesenthal.”

IN 1964, WORKING ON A TIP FROM WIESENTHAL, Joseph Lelyveld, a young reporter for The New York Times, knocked on the Queens front door of Hermine Ryan (née Braunsteiner). Ryan’s husband said he was unaware of his wife’s past as a Nazi camp guard at the Maidanek death camp in Poland. She, however, did not put up a front, greeting Lelyveld at the front doorstep: “My God, I knew this would happen.”

The headline of Lelyveld’s article, which was published on July 14 of that year, played with the contradiction of lifestyles and became a larger metaphor for the trickery entailed in survival after the atrocities committed during the war: “Former Nazi Camp Guard Is Now a Housewife in Queens.”

Ryan had only become an American citizen in 1963, having concealed a criminal past from the American government. She had actually served prison time in Austria after being convicted of assassination, infanticide, and manslaughter in Ravensbruck in 1941 and 1942.

Ryan became the first United States citizen to be extradited for war crimes. After being sentenced to life in prison in Germany, she died without media mention in 1999 at the age of 79.

An estimated 10,000 Nazis entered the United States as immigrants after the war. Some sources dispute this number as mere speculation, but what is indisputable is that Nazi war criminals entered the country as part of the post-war migration — either as displaced persons or post-war refugees, many having traveled circuitous routes to live in attempted anonymity.

“People have said to me that they came in and recognized on the boat … someone who had been a guard in a camp,” says Mark Weitzman, the Director of Government Affairs of the Wiesenthal Center, referring to Holocaust survivors who have come to him with tips. “They were too scared to report them” at the time, Weitzman adds.

Tips still come in to the Wiesenthal Center, but old age and the march of history has slowed the tips down to just a trickle — a handful or so a year, says Weitzman. Taking a case from suspicion through to conviction requires many elements to line up.

“What you need is not just evidence; you need a person who is physically and mentally capable of understanding the charges and standing trial,” explained Weitzman. “We are not looking to prosecute people who are suffering from Alzheimer’s.”

Public and political support on an international level for the work that Zuroff does has been mixed, for reasons both vague and, like Weitzman addressed, seemingly practical.

“What’s the likelihood of a 90-year-old Nazi war criminal committing murder again?” posed Zuroff. “The countries figured it out. All they have to do is wait it out — ignore the pains in the ass like me.”

THE UPHILL BATTLE FOR JUSTICE in modern society isn’t helped by the online compendium of misinformation associated with the Holocaust. “It’s actually gotten harder,” Zuroff says of his work.

In the Internet’s darker corners, the Nazis have an almost cult-like following, with a counterculture based around denial, lore, and mythology. To some, Hitler never died. To others, the Holocaust never happened. For others still, secret “proof” fuels hateful propaganda that conflates the real search for Nazis with fantastical connective threads.

Parsing through the detritus created by a rich compendium of factual accounts and fictional representations of World War II has fallen in the United States to an arm of the government that has been operating since 1979 with relative success: the Office of Special Investigations (OSI).

According to Eli Rosenbaum, the Director of Human Rights Enforcement Strategy and Policy (HRSP) for the Justice Department’s Criminal Division, formerly the OSI until 2010, his agency is in sole charge of taking “legal action against persons who participated in Nazi-sponsored acts of persecution.” He added that the OSI had been given an “A” rating by the Simon Wiesenthal Center every year until 2011 since the inception of its “Investigation and Prosecution Report Card” in 2001. The past three years were not included on the list, though it is unclear why.

Stacked against 44 other countries, including Syria, which has scored F’s consistently; Germany, with B’s, C’s and one “A”; and Argentina–C’s, D’s, and E’s–the OSI claims that during a 20-year period they have successfully prosecuted more World War II cases than have all of the other countries of the world combined.

In an email, Rosenbaum said that the OSI has brought cases to date against 137 persons and has been successful in cases against 107 of these individuals.

It’s because of the OSI that Efraim Zuroff has been able to largely leave the United States alone and instead be a “nudnik” — a label he gave himself that means a nuisance or a pest in Yiddish — to countries that have shown less success or ambition at rooting out the Nazis in their own backyards. It’s not that these countries are sympathetic to Nazis, says Zuroff, they just lack “political will.”

* *

PETER CARR OF THE U.S. JUSTICE DEPARTMENT’S Office of Public Affairs helped me to lock down just how successful the U.S. Government has been in its hunt for Nazis in America. After being denied an interview with the Director of the HRSP, Rosenbaum, I was instead sent via email the Department’s “USA Bulletin,” a comprehensive report on the OSI dated January 2006.

But it’s 2014 and a lot has happened since the Demjanjuk case in 2011, which changed the legal precedent for prosecution of Nazis in Germany. Prior to this case, proving and convicting Nazi war criminals for specific acts was next to impossible.

“Death camps don’t provide a lot of eye witnesses,” says David Rising, the Associated Press’s chief correspondent in Berlin, when I called him on the phone. Rising, who has been covering German government and politics for more than ten years, said that “aside from the highest ranking [Nazis], they never convicted anybody.”

Berlin being the de facto central location for Nazi investigations, Rising supposed, when pressed, that he was an expert on the topic. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that his degree is in history, the Second World War, and Holocaust studies.

“They’ve launched all these new investigations,” Rising says of the Demjanjuk case. “It sort of breathed new life into the investigation of death camp guards.”

Just one day before I interviewed Rising, he’d written a story on Oskar Groening, a 93-year-old former Auschwitz guard who was charged by German prosecutors this past September with 300,000 counts of accessory to murder for serving as an SS guard at the Auschwitz death camp.

Groening was one of thirty Auschwitz guards against whom the German special prosecutor’s office sought to pursue charges of accessory to murder, according to an earlier Rising report at the beginning of September.

After the 2011 ruling, Federal prosecutors in Germany conducted a new survey of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp and concluded that no one could have been there for more than a day or two without learning that people were being gassed to death and their bodies incinerated at the site, Rising noted in his article.

He reported that about 1.5 million people, mostly Jews, were killed at the Auschwitz camp alone between 1940 and 1945. In May of this year, investigations into the Majdanek death camp turned up around 20 former guards who could face charges, leaving four of the six total death camps remaining for review: Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor and Treblinka.

And, as if written by an unknown force to create a plot twist, major news broke this month of newly uncovered gas chambers that were buried for years at the Sobibor Death Camp.

“Whenever you write these stories, you get a lot of people who say, ‘Can’t you just leave these 94-year old guys alone?’” said Rising. “But you also get comments that say, ‘Thank you, thank you.’”

It is perhaps an odd coincidence — or perhaps not — that an ongoing investigation into Michael Karkoc, a 95-year old retired Minnesota carpenter who was found to have been a former Nazi commander who ordered the massacre of dozens of civilians in Chlaniow, Poland in 1944, was born of an AP investigation. Karkoc’s family denied the allegations to the press.

“The Karkoc case is different,” Rising told me. “For him they could bring murder charges. He’s even rarer as things go.”

Rising, who has been following the case closely, told me that German prosecutors have opened an official investigation into Karkoc, but that no charges have been announced.

The Department of Justice told the Associated Press in November of last year that they were aware of the allegations against Karkoc, but “generally do not confirm or deny whether an individual is under investigation.”

Referencing the above-mentioned article, Carr, the Justice Department public affairs official, wrote in an email that “We have no additional comment relative to Mr. Karkoc at this time.” Carr added that there was no further update on another controversial issue, specifically involving a leaked version of an OSI report dated December of 2008.

The 600-page report was obtained by The New York Times and published in full in November of 2010. With the word “Draft” stamped horizontally across each page’s center in capital letters, the report was released but heavily redacted by the OSI in response to a Freedom of Information Act request for the report by the National Security Archives.

Major findings in the report show “new evidence about more than two dozen of the most notorious Nazi cases of the last three decades,” according to the Times article. Most importantly, according to the Times, the report concludes that “American intelligence officials created a ‘safe haven’ in the United States for Nazis and their collaborators after World War II.”

The article also reported that the Justice Department said the OSI report was the product of six years of work, was never formally completed and did not represent its official findings. The Justice Department told the Times that the report had “numerous factual errors and omissions.”

I requested the original comment from the OSI but have not yet received it.

* *

THE WORLD OF NAZI EXPERTS, when surveyed closely, is really quite small. Names like Simon Wiesenthal, Efraim Zuroff, Eli Rosenbaum, and David Rising surely come up, and repeatedly.

Prod deeper, and you’ll find a somewhat unexpected name: Craig Gottlieb, who has earned a minor celebrity status for his work as a firearms and weapons expert on the popular antiques appraisal TV show “Pawn Stars.”

“I think I’ve filmed over 40 episodes,” Gottlieb told me over the phone from San Diego.

Gottlieb’s moniker as the “history hunter” comes from his work as a dealer in military antiques. Gottlieb tells me that in the collector world, his is one of the world’s top five collections, measured by volume (he has a warehouse in Solano Beach, California). He speaks with fervent passion, but, as he cautioned when we began our telephone interview, only if he’s interested in the conversation.

Luckily for me, he was. I’d called to ask about Nazis in the United States, having drummed up more information than I could process. Gottlieb, whose passion is World War II, has been under fire for a controversy of his own: his purchase of (and desire to sell) Hitler’s uniform. The Holocaust, as Gottlieb described it, is “captivating. It’s like a train wreck you can’t help to look at.”

Out of the official loop of experts and Nazi Hunters, Gottlieb was frank and spoke candidly and with fan-like zeal about a curious character he met recently: a German World War II soldier whose name Gottlieb is keeping private until he reveals it himself in a documentary he has already started making on the subject.

“My friend was born in Dresden. He leaves Germany at seven or eight,” said Gottlieb, excitedly. “They move to Chicago in the twenties. He speaks with a Chicago accent.” Gottlieb relates that in 1938 or 1939, his friend’s family sent the teenager back to Germany because they thought he’d receive a better education.

“He sails to Hamburg,” said Gottlieb. “Shortly thereafter, Hitler invades and because he was born in Germany, he’s considered a German national. They won’t let him leave.” The now 90-year-old man lives in California.

A buck private during the war, Gottlieb’s subject returned to America afterward and has been living here quietly since. At get-togethers, most people know he’s a veteran; when he tells them he fought for the Germans, says Gottlieb, most people don’t have a problem with it.

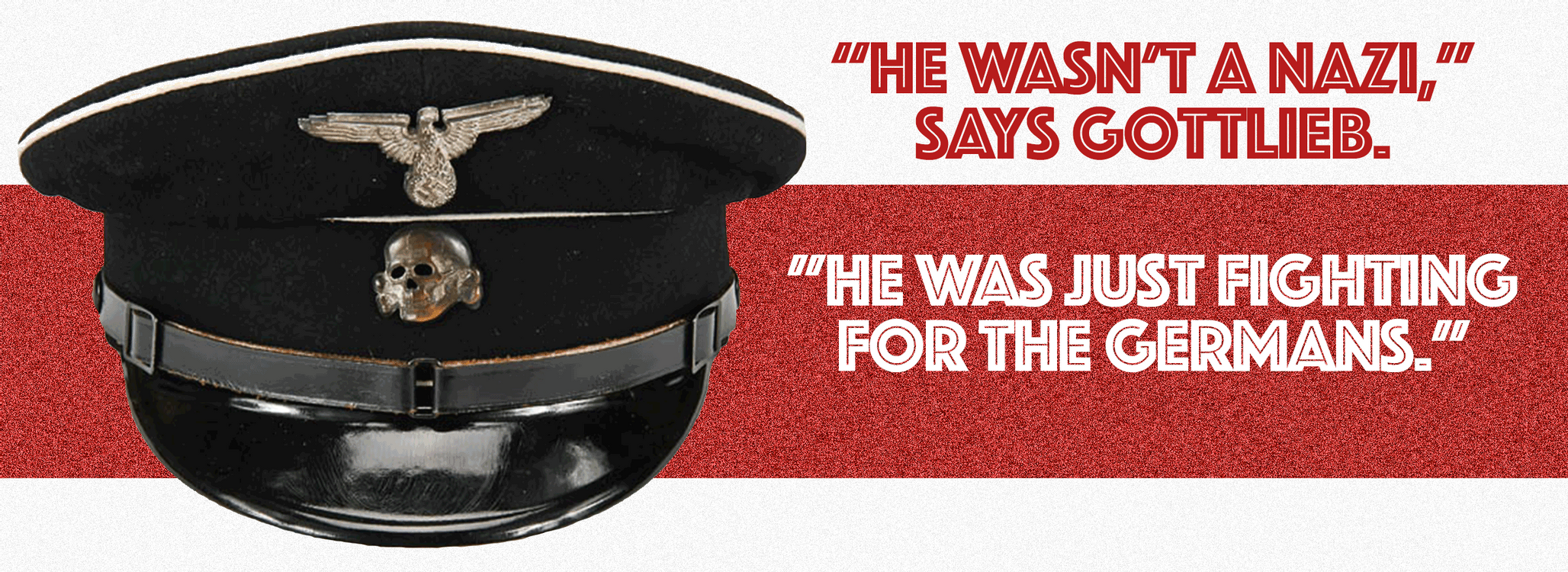

“His insignia had the swastika,” said Gottlieb. “He wasn’t a Nazi. He was just fighting for the Germans.”

I’d reached out to Gottlieb hoping he’d have access to further information concerning Karkoc, the 95-year-old Minnesotan who was found to have been a former Nazi commander. In contacting a major collector of historic Nazi paraphernalia, I had hoped to tap into a shadow world of secret Nazi rumors, connected to those whose names would only be whispered in unofficial, non-governmental circles.

Reality is a bit different. “I don’t have much information about Nazis living in the U.S.,” Gottlieb admits. “I’ve got Hitler’s uniform — legitimately — and medals and hat. If you’re looking for Nazis in America, I guess that’s the closest thing you’re going to get.”

* * *

Rebecca White is Narratively's Director of Operations, as well as an editor and regular contributor to the publication. Her work has appeared in such outlets as The New York Times and Al Jazeera America, among others.

Cover photo by Petri Krohn

This story was created in partnership between The Wilson Quarterly and Narratively.