Fall 2016

The Price of Silence: Family Memory of Stalin's Repressions

– Izabella Tabarovsky

The discovery of her great-grandfather’s name in an online database of Stalin's victims led Izabella Tabarovsky on a journey to explore and honor his life, while considering the personal and national consequences of the silence that continues to envelop repressions in Russia.

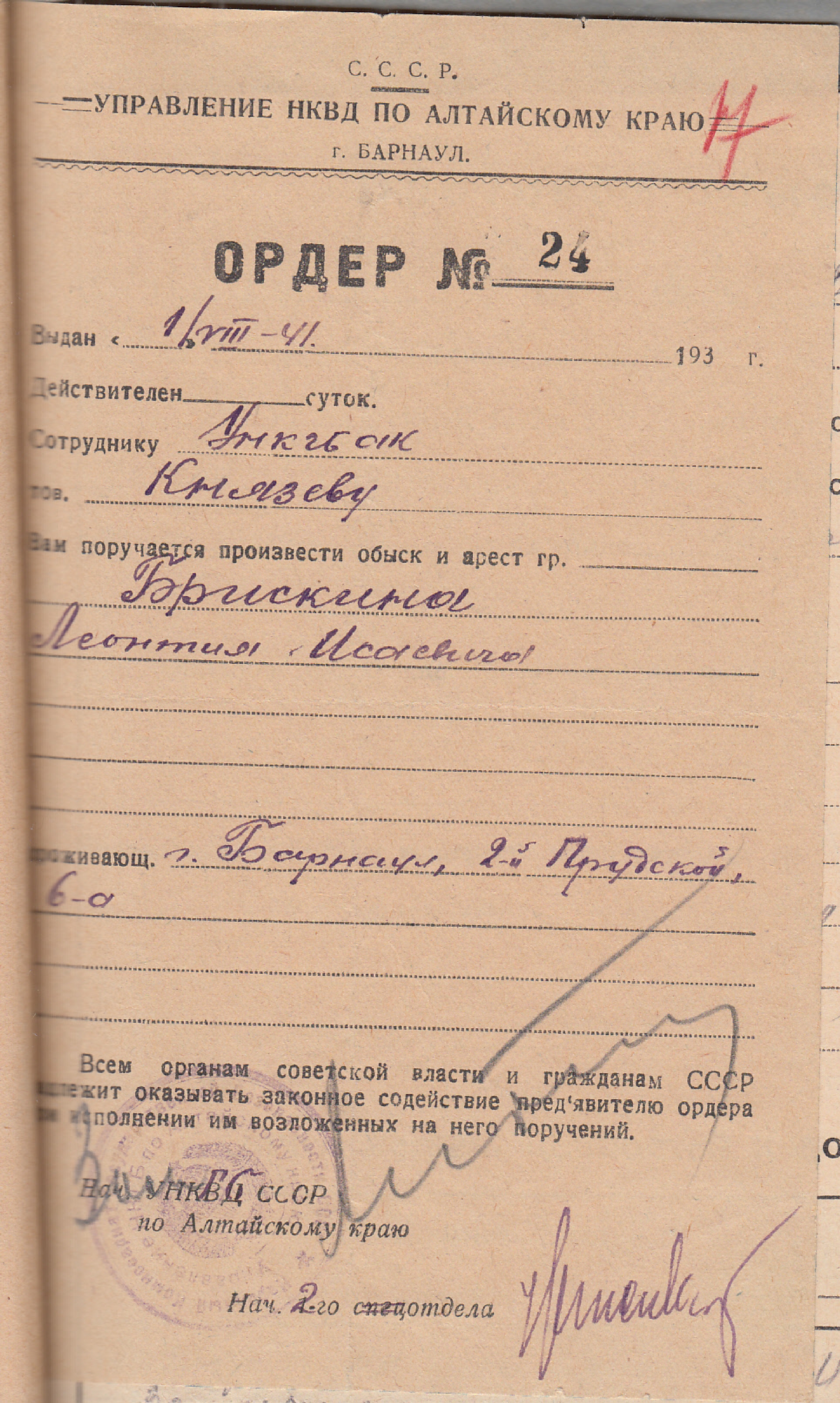

In August 1941, my great-grandfather, Leonty Briskin, was taken from his home in the middle of the night in the Soviet Siberian city of Barnaul. He left behind his wife, Sarah, and their three daughters – Mari, Riva, and Basya. Forty-four at the time, Leonty was tried by a “troika” — an extrajudicial commission authorized to sentence defendants without a full trial — and judged to be an “enemy of the people,” for which he received a sentence of 10 years of imprisonment. He was rehabilitated during the Khruschev Thaw in 1956, when his case was reviewed and closed for lack of criminal offense. By then he had long been dead. According to the death certificate my family received in 1956, he had died in prison in Novosibirsk on February 29, 1944.

Forty-four at the time, Leonty was tried by a “troika” — an extrajudicial commission authorized to sentence defendants without a full trial — and judged to be an “enemy of the people,” for which he received a sentence of 10 years of imprisonment.

Fortunately for us, his memory lived on. Sarah refused to forget. Though she was only in her early 40s at the time of his arrest, she never remarried but spent the rest of her life living alternately with her married daughters. Once in a while she would go to a local cemetery, find a spot there, and silently stand over it with her eyes closed. She often took along my father, then a young boy.

Sarah’s silence haunts me. What was she doing in those moments? Was she saying a silent Kadish over a proxy for her husband’s empty grave, knowing she would never be able to say it out loud, in a Jewish congregation? Was she simply speaking to her husband in her heart, sharing with him what was happening with his growing family?

Once in a while she would go to a local cemetery, find a spot there, and silently stand over it with her eyes closed.

In 1956, it was her daughter Basya who went to the local offices and received the notice of his posthumous rehabilitation. Family lore has it that she threw the notice in the official’s face and walked out with the words “Rehabilitated?! He never did anything wrong!” And while this may or may not have occurred in just that fashion, the heroic story of personal resistance, small though it was, may have allowed members of the family to recover a sliver of dignity and some sense of personal power. The family continued to treasure the memory of Leonty, passing it on from generation to generation.

* * *

This story of a family preserving and treasuring the memory of a victim of repression is unusual for Russia. In Soviet times, authorities actively discouraged personal memory. Among the archival materials kept in the basement of Memorial, a nongovernmental organization dedicated to preserving the memory of Stalin’s repressions, where I visited a few months ago, one can see family photos where individuals blotted out their loved ones’ faces with the characteristic purple ink of the era or cut them out completely. Families often broke off correspondence, even where it was permitted, out of fear and shame. All talk about the person ceased.

In the meantime, the trauma of the atrocities perpetrated during Soviet times has likely touched the family of virtually every person born in Russia in the 20th century. As many as 50 to 55 million people may have suffered in the terror and repressions of 1917-56, including those who were killed, exiled, persecuted in politically-motivated campaigns for petty disciplinary violations, sentenced to slave labor, forcibly displaced, or moved thousands of miles across the Eurasian continent — as well as their families, who lost all rights, were deprived of their homes, and were stigmatized as the parents, spouse, or children of an enemy of the people. In 1937, the bloodiest year of the regime, the government murdered an average of 1,000 of its own citizens every day. Every seventh Soviet citizen, if minors are included, or every fifth adult was a victim.

According to German psychoanalyst Werner Bohleber, tragedies of this scale produce massive traumatic impact on societies — so much so that their reverberations can be felt on the social level generations later. Yet, in the post-Soviet space, the personal and national traumatic impact of Stalin’s repressions remains largely unaddressed.

While Stalin’s atrocities became a subject of condemnation after the fall of the Soviet Union, the state never decisively dealt with the issue of guilt and innocence. In the absence of a legal framework to hold the perpetrators liable, Russian society has continued to live in something of a moral equivalency about the repressions. The unconsidered reaction that “if they arrested him, there must have been a reason” still exists. Within families, silence persists, and feelings of guilt, shame, and fear continue to keep the lid on questions and memories.

Meanwhile, some recent research into the transgenerational psychological effect of Stalin’s purges allows us to begin to consider the possible consequences of this silence. A joint Russian-American study conducted in the early 1990s, demonstrated that the concealment of trauma in previous generations resulted in lower functioning among grandchildren. Specifically, and most strikingly, if surviving family members tried to suppress the memory of the family member who had been taken from the family, the following generations had lower functional abilities. By contrast, families that preserved the memory of the repressed had higher levels of functioning.

The authors also found that “a personal research effort into family history and the ability to actively protest political coercion were positively related to social functioning.” But in Russia, this impulse to research one’s history – so typical, for example, for the descendants of another tragedy of the 20th century, the Holocaust – is absent in the majority of the population.

* * *

That the memory of traumatic events may be transmitted through generations has also been demonstrated in recent studies of Holocaust survivors. Summarizing some of the findings in his Warped Mourning: Stories of the Undead in the Land of the Unburied , Alexander Etkind writes that “the second, and even third, generations following a social catastrophe manifest ‘subnormal’ psychological health and social performance, and this is claimed to be true both for the descendants of the victims and the descendants of the perpetrators.”

In 2015, a team of scientists at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital investigated the children of 32 Jewish men and women who had experienced concentration camps, had lived in hiding, or had witnessed or experienced torture. The genes of the children showed alterations that made them more prone to stress disorders. According to the scientists, this kind of alteration “could only be attributed to Holocaust exposure in parents.” The researchers concluded: “This is the first demonstration of an association of pre-conception parental trauma with epigenetic alterations that is evident in both exposed parent and offspring, providing potential insight into how severe psychophysiological trauma can have intergenerational effects.”

And in another intriguing experiment, made public in 2013, scientists at Emory University worked with mice to show that certain fears in these animals could be passed on to next generations. When they coupled the fragrance of cherry blossoms with the delivery of a small electric shock to mice, the animals learned to fear the fragrance. They eventually began to shudder when presented with the fragrance, even in the absence of a shock. Remarkably, their offspring were found to have the exact same response to the fragrance. Just like their parents, they shuddered at the smell, even though they had never experienced electric shock coupled with it.

While scientists are still in very early stages of exploring the epigenetic aspects of the transmission of traumatic memories, the very possibility of that suggests that passage of time alone may not be enough to wipe out the impact of those experiences – nor is deliberate policy of forgetting. Traces of traumatic experiences may remain, influencing how we live our lives in the present, both individually and as a society.

***

This idea appears to be particularly relevant in today’s Russia, where the signposts and memories of the repressions are disappearing both from the larger society’s inner landscape and its external maps. Museums dedicated to understanding the gulag system are closing down. As the victims of and witnesses to the repressions depart, less and less direct information remains available for historians to study this tragic period of the 20th century.

And yet, individual stories suggest the magnitude of the personal psychological impact of the repressions, generations later. In a paper presented at a Russian-German conference on historical trauma, Svetlana Malimonova, a psychotherapist, wrote that “both family therapists and experts who work with systems, confirm that children take on unresolved traumatic energies from previous generations.”

Reflecting on her own life, Malimonova related the story of her grandfather, whom she never knew. Already in an adult age, she learned from her mother that during Stalin’s time, he was forced to bear false witness to incriminate the innocent. “This caused him significant suffering,” she writes. “He experienced his greatest fear when people, against whom he bore false witness, began to return from camps. He always awaited retribution and was very afraid. Leaving for work, he warned his children that if today he didn’t come home, it meant that he was killed.” Noting that he had died 20 years before she was born, she concludes: “I must have received this fear and the rule of ‘don’t stick out’ from my grandfather through my mother.”

Another psychologist, Maria Timofeeva, recounted her client’s recurring nightmare of being arrested, despite having committed no crime, and taken to a place of exile in a train car. Even though she was innocent, both she and her family had “known” that this was always supposed to happen. Her arrest had somehow been “a given.” Timofeeva goes on to write that she has heard the same kind of a dream recounted by another client, surmising that this is something of an archetypal dream for a Soviet person.

Since I began researching this subject, I have heard stories of people living in expectation of searches and arrests with no particular reason – except that family members in previous generations had experienced that.

I have lived in the United States for 26 years, and yet I, too, know a variation of this fear. It arises every time I travel back to Russia. Any encounter with representatives of the Russian state may provoke it: The border guard at the Sheremetyevo airport flipping through my passport pages a few moments too long. The hotel receptionist telling me I need to leave my passport with her so she can register it with the “organy” (the secret police). The watchful eyes of policemen near the scanners at entrances to public buildings. It comes alive any time I face representatives of that state, of that system.

It also arises when I simply read about contemporary political persecutions in Russia. I experience those stories as highly visceral, as though they are happening or could happen to me. And it makes me wonder how many of those us who came of age in the Soviet Union – and even the post-Soviet generation – live with that kind of fear.

* * *

A few months ago, I found my great-grandfather’s name in Memorial’s online database. One of my relatives, a grandson of Leonty’s who still lives in Barnaul, went to the local archive of the FSB, the successor to the KGB, and requested a copy of Leonty’s file. I soon had the scans in my inbox.

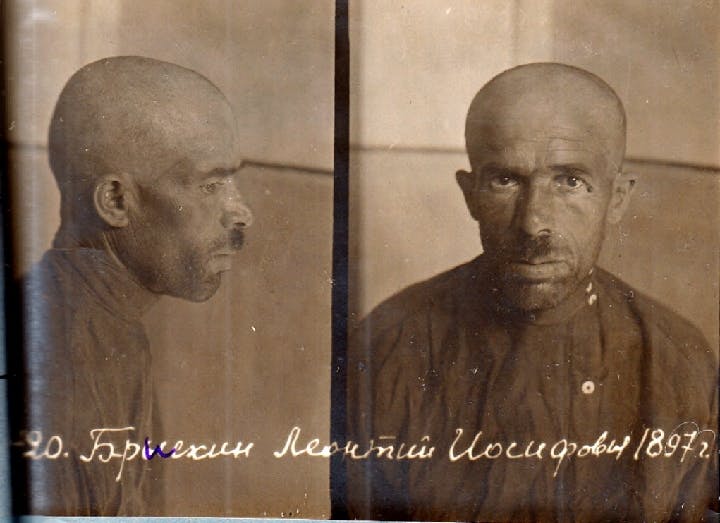

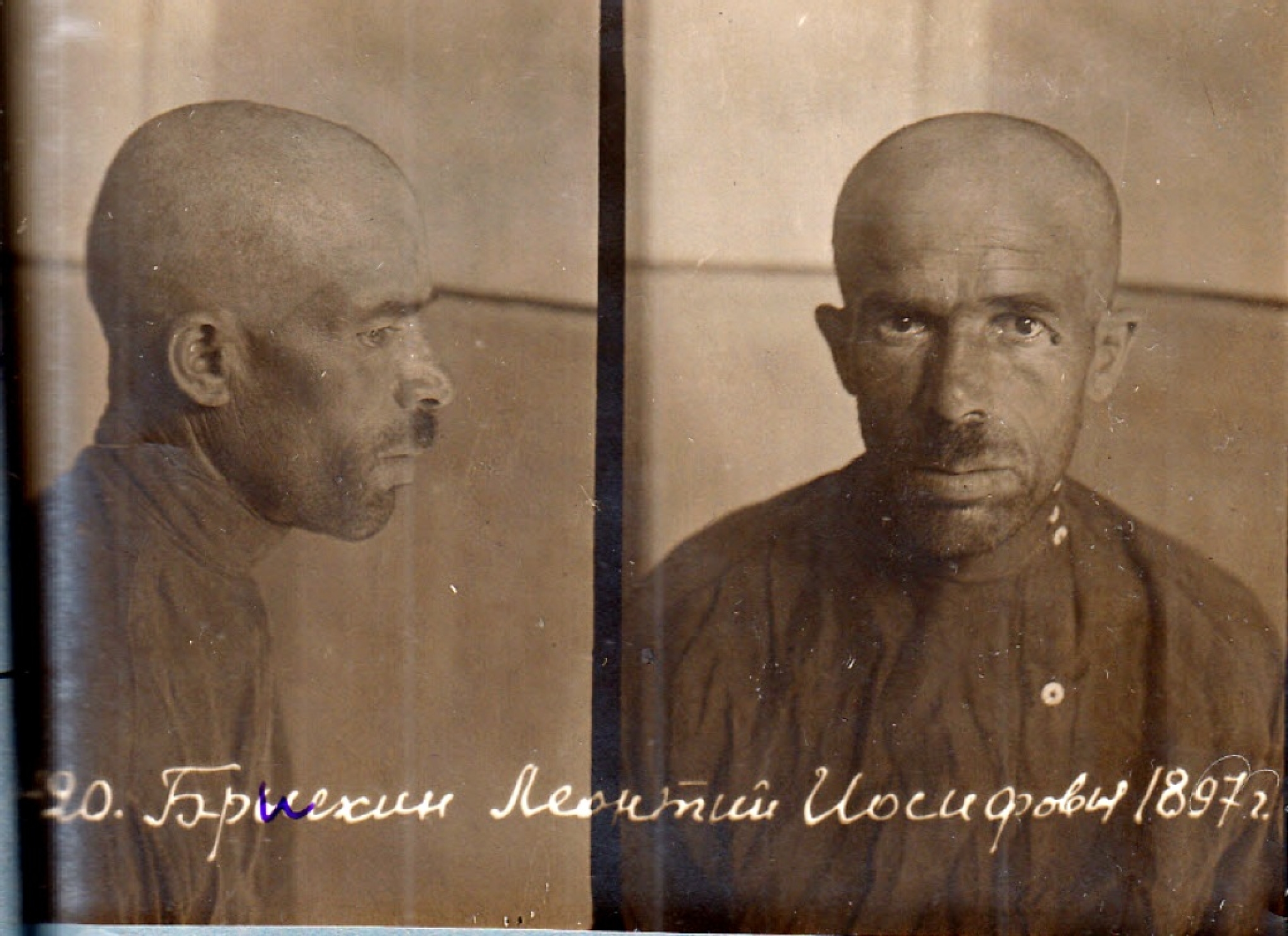

For the first time, I saw my great-grandfather’s face – a mugshot of a scared, downcast man with a knit brow. I read through the handwritten record of the interrogations and his accusers’ claims. I read the sentence and the conclusion of the rehabilitation court. I learned that by the time of his arrest, he had already lost his brother: In 1938, his file stated, his brother Abram had been “extracted by NKVD” – the blood-curdling, dehumanizing Soviet-speak for “arrested” – and disappeared. In the file, which scrupulously lists the addresses of all of Leonty’s living relatives, Abram’s address is left blank. It’s as if by the time of Leonty’s interrogation, his brother had already ceased to exist. He probably had.

For the first time, I saw my great-grandfather’s face – a mugshot of a scared, downcast man with a knit brow.

And that is when I understood. I understood the fear that had always lived in my grandmother Mari, a woman of 22 at the time of her father’s arrest and disappearance. Mari spent the rest of her life speaking in quiet semitones, hushing anyone who dared bring up politics in her presence. She had an endless number of locks and chains on her door, and every evening concluded with a ritual of locking those up one after the other. As a child, I used to wonder what she was so afraid of and who could possibly break through that heavily armed door.

I understood my father’s visceral hatred of the system and determination to emigrate, which was there for as long as I remember myself. And I now better understand the nature of my own fear – the fear that I have carried with me, largely unconsciously, all my life and that today, after 26 years as a resident of another country, returns the second I set foot in Russia.

* * *

With the Russian state uninterested in an honest national conversation about the repressions – the only way, according to Bohleber, for a nation to extricate itself from the traumas of past generations – the few private initiatives that do exist and look to restore historical memory for individuals and their families become all the more important. Most aim at personifying history, an act particularly important in a country where the role and importance of individuals had been subsumed by the system.

One of these is Last Address, run by the journalist Sergey Parkhomenko. Working closely with Memorial, Parkhomenko modeled his initiative on the German Stolperstein project, which memorializes victims of the Nazi atrocities by installing “stumbling stones” inscribed with individuals’ names in the pavement of European cities.

In a similar attempt to somehow physically embody the departed, Last Address hangs a small metal plaque on the wall of the house or apartment building where the person last lived before his or her final arrest. The plaque bears the name of the person, his or her profession, dates of birth, arrest, and death, and information about the place and manner of death and rehabilitation. The motto of the movement is “One Name, One Life, One Symbol.”

Some 340 plaques have been installed so far in 22 cities throughout Russia, but the demand far outstrips supply. Last Address now has some 1,500 applications, and a few months ago Parkhomenko appealed to his nearly 150,000 Facebook followers to volunteer for the project to help with the most time-consuming work of all – negotiating with the owners of the buildings and houses to secure their permission to hang the plaque. He emphasized the urgency: In many cases, the applicants are people in their 80s and cannot wait much longer to get the plaques installed.

And yet, as Parkhomenko likes to say, the idea is not to fill Russia with memorial plaques. Rather, it is to start a conversation – among family members, neighbors, passers-by. “Each plaque,” Parkhomenko told me, “must be initiated by someone. We don’t do anything until we receive an application. Behind every plaque there is a real person who requested it on his own initiative.” In this too, there is an important element of fostering a sense of empowerment and responsibility to personal family history as well as the history of one’s country.

I first met Parkhomenko a year ago, when he was a first-time fellow at the Kennan Institute in Washington, DC, where I work. In a casual dinner conversation, he told me about the initiative. It was this conversation that spurred me to action. Over the following months, my family in Russia and Last Address worked to confirm information on my great-grandfather, get his file, determine the address where he had lived before his arrest, locate the house, and negotiate with its new owners. The precise text of the memorial plaque had to be agreed on as well.

Earlier this year I traveled to Barnaul to witness the installation of the plaque. By sheer miracle, the wooden single-family house still stood, though the new owner had renovated it to make it look more modern. I did not anticipate the emotional impact that this event would have on me. It was as if by recovering and honoring Leonty Briskin’s name, I had helped close a wound that had afflicted three generations.

Members of my family – especially Leonty’s three surviving grandchildren – felt the same way and eagerly shared memories of the past, as well as stories they had heard from their parents of how their families had fared after Leonty’s arrest, as years stretched into decades. It was as if by recalling the presence of a man whose own life had been terminated secretly and too early, we were able to complete a grieving process that had never been done properly. It did not matter that most of my family are no longer alive to complete the work. Just as psychological studies suggest, the process of embracing the past and connecting it to the present mattered very greatly.

It was as if by recalling the presence of a man whose own life had been terminated secretly and too early, we were able to complete a grieving process that had never been done properly.

For Parkhomenko, the fact that my family’s personal commemorative project generated conversations among three generations across two continents, three countries, and 11 time zones is precisely what Last Address is about: to lift, even if only just a little bit, the fog of silence that enshrouds the millions of Russia’s unburied and the un-mourned.

* * *

Today, the assault on Russia’s national historical memory continues. Memorial has now been declared a “foreign agent” by the Russian state – a label that almost always results in cessation of operations. But even if it were able to continue its fight, it would not be enough. To make a real dent in this ever-thickening wall of silence will take participation from the entire society.

This concerns not only those living in Russia. We all – everyone who is in one way or another part of that culture and privy to that history – need to be taking responsibility for our own families’ pasts. We need to be asking each other about our stories. We need to provide a space for those who want to speak, to learn more, to do so. We need to do the work of mourning that those who came before us couldn’t accomplish.

Would these acts of private remembrance matter beyond the personal? Would they make a difference for Russia as a nation? It’s hard to know. But that is the only thing we can do to break through the thick silence surrounding that tragic period. It is the only thing we can do to prevent the price of silence from climbing even further.

Would these acts of private remembrance matter beyond the personal? Would they make a difference for Russia as a nation? It’s hard to know.

* * *

Izabella Tabarovsky is a scholar and manager for regional engagement with the Kennan Institute. Her articles have appeared in Newsweek, the Times of Israel, and on the Wilson Center’s Kennan Cable, among others.