What does it mean for a video game to be moral?

– Caitlin Moniz

Traditionally, games lead players to think strategically, not ethically. That's changing in the era of "Grand Theft Auto."

Video games have always been a source of ludic entertainment, but can they present players with real moral choices? Miguel Sicart, associate professor at the Center for Computer Game Research at IT University Copenhagen, explores the idea that as video games move from amusements to art, game designers should be increasingly concerned with presenting moral dilemmas in their games.

Gameplay, lacking a formal definition, is described by game theorist Jesper Juul as a result of the interaction between “1) the rules of the game; 2) the player’s pursuit of the goals (i.e. the player seeks strategies that work in light of the emergent properties of the game); and 3) the competence of the player and his or her repertoire of strategies and playing methods.”

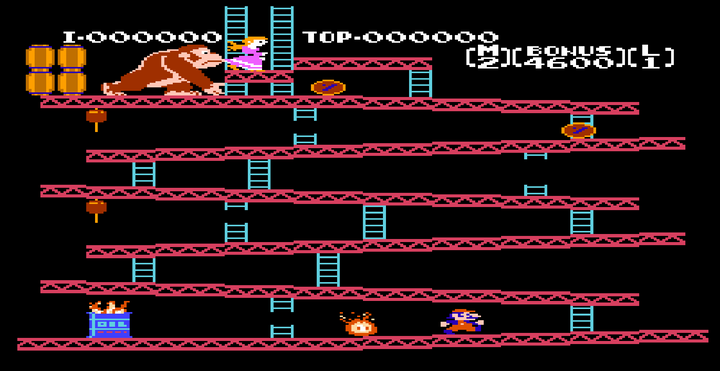

Traditionally, game development has produced rational and calculated playing, with players “rewarded and encouraged by design elements, such as incentives and goals.” Players are led to think strategically, not ethically.

That has changed drastically in the age of video games with ethical dilemmas and subversive storylines. Take, for instance, Grand Theft Auto V, an enormously popular video game known for its freewheeling approach. Players are welcome (encouraged, even) to roam the city and do as they please — steal cars, solicit prostitutes, and murder random civilians, etc. — all within an “open world” larded with satirical elements, like a Facebook stand-in called “Life Invader,” and absurd political talk radio (one station, WCTR, uses the motto “Real talk. Real issues. Real experts. Real patronizing).

The age of immersive video games, then, presents a fundamental shift in how we should think of games: players aren’t interacting with toys; they’re taking part in a performance. Video games with ethical elements are thus an artistic journey “that changes the person who experiences it,” Sicart writes, quoting Hans Georf Gadamer.

Games are being thought of less as toys than as an artistic experience

Ethical game playing, says Sicart, “happens when the game affords a different type of thinking and acting, so that the player as ethical agent is invoked.” Rather than having choices presented “as either/or, good/bad binaries with relatively predictable outcomes,” games should strive to present “no clear narrative-or-system-driven indication as to what choice to make.” Without checkpoints or goals to guide the player, she can employ her own values to make decisions.

Ethical gameplay has grown in prominence as more and more “open world” games contain what Sicart calls “wicked problems” — situations in which information is confusing or incomplete, consequences are unclear, and ethical thinking is required. If game designers can present wicked problems in their systems, Sicart imagines that players will be forced to “pause in their instrumental play and apply ethical thinking to their in-game choices.”

One such “wicked problem” can be found in Fallout 3, a video game set in a dystopian, post-nuclear apocalypse Washington, D.C. In one quest, “the players face a dilemma: They can eliminate all ghouls in the proximity of the Tower, help the ghouls kill the humans, or negotiate peace between both.” While a player’s natural impulse may be to side with the humans, such a decision is complicated by the fact that ghouls are time and again presented as the world’s “most pacific denizens.” Players must make choices informed, in part, by their own morality.

Yet even as they present players with “wicked problems,” Sicart sees games like Fallout 3 presenting two major design obstacles to fully ethical gameplay: one, games are always solvable; two, that games are reloadable (allowing users to regenerate certain points in the game and start from there when their character dies or they next turn on the game). Solvable games, says Sicart, “are attractive because, unlike moral problems, they are encapsulated systems that provide a resolution to the action.” Reloading lets the player return to a previous state if he or she makes a mistake, so that “the potential ethical implications of that choice are diminished.”

In real life, ethical considerations can be particularly taxing because they have actual, real-world consequences. Lacking those — with players able to respawn at benchmarks of their choosing en route to a glorious victory at the game’s end — ethical conundrums may themselves reverse the rethink on the nature of games: moving video games backwards from an artistic experience to just another toy for amusement.

The Source: "Moral Dilemmas in Computer Games" by Miguel Sicart. DesignIssues, Summer 2013.