Fall 2022

Trust in Values-Based Supply Chains

A resilient supply chain requires having the right technology and partners you can trust.

Even with all the political, economic, social, and cultural differences that divide Asia, an unshaken belief in trade as a pathway for growth still prevails across the Indo-Pacific. Although faith in trade has traditionally been a force unifier in an otherwise disparate region, disruptions in supply chains and the rise of new values for economic engagement are increasingly becoming yet another factor driving a schism across Asia.

The 2020 outbreak of COVID-19 turned many long-held supply chain beliefs on their head, and Asia’s leading trading nations are now scrambling to find their footing in the newly emerging economic order. Once the gold standard in promoting trade efficiency, the just-in-time supply chain management system that had been championed by Japanese automobile group Toyota has come to exemplify the fragilities of a hyperconnected global production network. Keeping inventories to a minimum proved to be a particular source of vulnerability during the pandemic, leading to border closures, hoarding, and other disruptions.

Evolving rules of engagement

While the worst of the shocks caused by COVID-19 may now be over, the world is far more attuned to the possibility of future crises that could strike without notice. What’s more, there is greater awareness that the global economy is disproportionately dependent on Asia for some of the most vital goods—from pharmaceuticals to advanced technology components to basic consumer goods—and that the Indo-Pacific is especially vulnerable to natural disasters, energy supply disruptions, and geopolitical tensions. Northeast Asia has always been vulnerable to earthquakes and typhoons, and is energy-poor. Geopolitical risks in the region, however, have begun to emerge as the greatest threats to economic stability and security as tensions with China escalate. Meanwhile, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has increased risks to the regional order, and Moscow’s vision for the Russian Far East could further destabilize Asia.

The good news amid the increasing risks to growth and stability is that Washington’s key allies in the region—namely, Tokyo, Seoul, and Taipei—have inherently remained protrade, and there has been no notable movement to retrench from the global economy. They largely share the economic values of the United States in their commitment to fair markets and the international order. They share a commitment to trade as a means for economic expansion, the need for global markets, and an inherent understanding of interdependence. Not only do they face challenges of limited natural resources, including their energy supply, but the smaller sizes of their domestic economies also push them to look outward for growth. At the same time, the pandemic has made clear that their diverse industries and technological capabilities make them drivers of global growth and economic security for the world.

The ability for governments to trust one another will also play an ever-larger role in establishing networks.

But the rules of economic engagement and supply chain resilience are evolving rapidly as countries race to prepare for external shocks and ever-growing geopolitical risks. As they race, we’re witnessing an inherently different approach to tackling the supply chain conundrum between the United States and its Asian partners, which could drive a wedge between the two sides at a time when Washington needs to work even more closely with like-minded governments in one of the world’s most vibrant regions.

Taiwan and the US-China technology war

Boosting domestic capabilities to produce goods has been a key Washington response to the pandemic, especially concerning critical technologies. Nowhere has this been more apparent than in the semiconductor industry, with the Biden administration signing the CHIPS and Science act in late August to provide more than $52 billion in subsidies for US chip production. The legislation directly responded to the dire shortage of semiconductors faced by the United States as it relied on chip imports from Asia. To be sure, the United States was hardly unique in needing to deal with chip shortages. In 2021, the global automobile sector alone lost more than $200 billion in profit when corporations were forced to limit production due to a lack of semiconductors. Companies including Ford Motor suspended production temporarily, and 11 million fewer cars were manufactured worldwide due to the lack of chips.

At the same time, the foreign policy drive to boost domestic capabilities of essential industries and develop cutting-edge technologies looms large. The White House made clear that the CHIPS Act is a key part of the US strategy to directly confront China in the longer-term technology cold war, and to ensure that the United States invests in its technology development capabilities. Yet there is growing unease among US Asian allies that Washington’s efforts to both reshore and near-shore production will make it increasingly challenging for countries to cooperate with and invest in the United States.

For a government like that of Taiwan, the impact of the United States’ decision to focus on domestic production of semiconductors and make headway in the technology war with China is especially acute. More than three-quarters of all chips are made in Asia, and over 90 percent of the most advanced semiconductors are produced in Taiwan, giving the island outsized influence in the global economy. In fact, Taiwan’s largest chipmaker—TSMC—has become critical to the United States’ strategy to ramp up its own semiconductor research and production capabilities. TSMC has already made headway in its plans to construct a $12 billion plant in Arizona, and a number of other Taiwanese chip suppliers are expected to invest in US production. It is a delicate balancing act for Taipei as it looks to maintain its competitive edge in the chip sector, while working with Washington to boost US self-sufficiency in the critical sector.

As governments scramble to develop new rules to share technologies and establish frameworks for digital cooperation and governance, efforts to reconcile competition with cooperation will be crucial.

Taiwan’s central role in the global semiconductor supply chain network has played no small part in mounting US interest in demonstrating public support for Taipei, even as it increases tensions between Washington and Beijing. For Taipei, however, Washington’s demonstration of interest and recognition of its position in the global economy is both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, there is greater awareness of the critical role that Taiwan plays in the technology-centered global economy, the challenges it faces in confronting the China threat, and its unique status in the international order. On the other hand, heightened US interest and highly visible political support have not only intensified cross-Strait military tensions, but the Taiwanese economy is facing greater risks of blockades from China in retaliation to US interests. The United States’ partnership with Taiwan must go beyond simply encouraging technology transfer from the island to US shores and offering it rhetorical support.

The trust test

As events unfold, the United States will need to work with like-minded governments and reassess what makes a strong partnership to develop supply chains that are resilient to external shocks—including geopolitical tensions. Working with partners and allies in building supply chain resilience undoubtedly makes economic sense. In the semiconductor industry, for instance, not only does it cost about $4 billion to build an advanced chip factory, but continual investments will needed to sustain and update the facility. To reshore chip manufacturing capabilities, a comprehensive ecosystem for semiconductor production will need to be developed, ranging from research and development to testing and packaging. Given the high labor and energy costs in the United States, the prospect of complete US self-sufficiency in developing, producing, and disseminating chips within US borders will be far too costly. Cooperating with like-minded countries will be essential to keep costs down, which remains a critical factor for supply chain sustainability.

But as security concerns take on greater importance in the development of new supply chains, the ability for governments to trust one another will also play an ever-larger role in establishing networks. The fact that TSMC produces advanced chips for US F-35 fighter jets and also supplies semiconductors for China’s Huawei Technologies means that there will need to be closer coordination between Taipei and Washington that goes beyond simply sharing chip development strategies and extends to establishing rules to protect competitive technologies.

The desire to establish supply chain partnerships that can be less dependent from China—if not entirely independent—has focused on ways to secure critical technologies that have been carefully developed through sizable investments by the United States and others. At the same time, one of the basic tenets of supply chains remains unchanged: their ability to boost business competitiveness and cost-effectiveness. The drastic disruptions to supply chains in recent years may have led to a greater push to reshore, near-shore, or “friendshore” vital supplies, but the need to keep costs down and for businesses to remain competitive is an enduring core value of supply chains. In short, governments may be on the same page when it comes to restructuring supply chains to bolster resilience, but the competitive nature of industries will—and should—persist.

As governments scramble to develop new rules to share technologies and establish frameworks for digital cooperation and governance, efforts to reconcile competition with cooperation will be crucial. It is imperative to develop relationships based on trust, which requires a traditional, analogue approach to growth. Clearly, Washington and its traditional allies in the region agree that supply chains based solely on cost effectiveness no longer meet the needs of a global economy confronting greater geopolitical risks.

Finding cooperation amid competition

Given all these factors, there is wariness about the United States’ commitment to working together with its allies and partners when it comes to developing new supply chain networks. One of the biggest questions is the extent to which the United States wants to be self-sufficient and limit cooperation with like-minded countries. As the Biden administration seeks to enhance the nation’s ability to withstand economic coercion and external shocks, there is growing guardedness outside the United States that Washington is pursuing an industrial policy that will focus more on foreign technology transfer than on international technology cooperation. The CHIPS act and subsequent export restrictions on semiconductors aims to cut China’s development of advanced chips development at its knees through stringent limitations and control of technologies being available in China. There may be numerous unintended consequences of the strategy, not least the prospect of alienating US allies and partners in joining Washington’s efforts to take similar action and abide by the export restriction rules.

Certainly, Tokyo, Taipei, and Seoul do not always see eye to eye when it comes to threat perceptions regarding Beijing’s aggressions or Moscow’s ambitions.

Shihoko Goto is the director of geoeconomics and Indo-Pacific enterprise and deputy director of the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center. Her research focuses on the economics and politics of Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, as well as US policy in Northeast Asia. A seasoned journalist and analyst, she has reported from Tokyo and Washington for Dow Jones and UPI on the global economy, international trade, and Asian markets. She is a columnist for The Diplomat magazine and contributing editor to The Globalist, and she was previously a donor country relations officer for the World Bank. She has been awarded fellowships from the East-West Center and the Knight Foundation, among others.

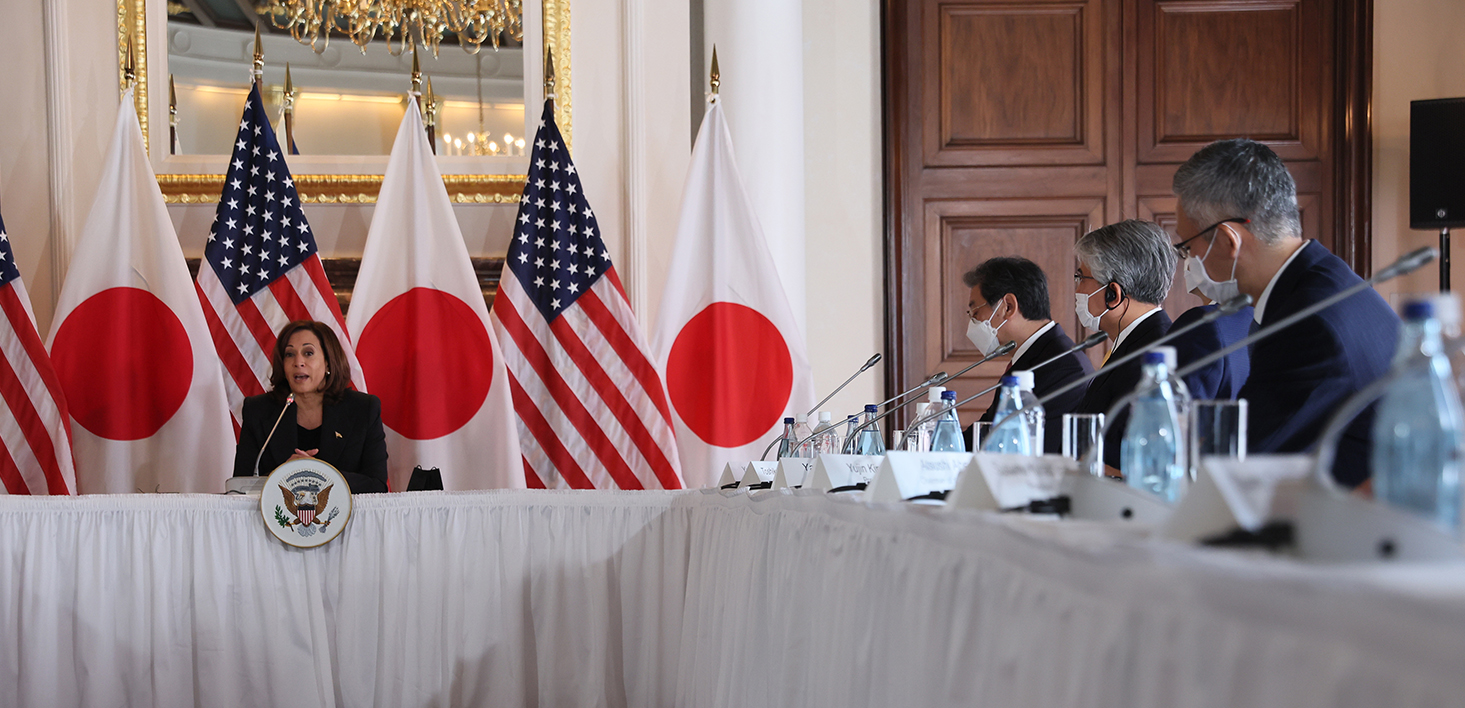

Cover photo: US Vice President Kamala Harris hosts a roundtable discussion with Japanese business executives from companies in the semiconductor industry, at the Chief Mission Residence in Tokyo. September 28, 2022. Leah Millis/Pool Photo via AP.