Fall 2007

Hide and Seek

– Hara Estroff Marano

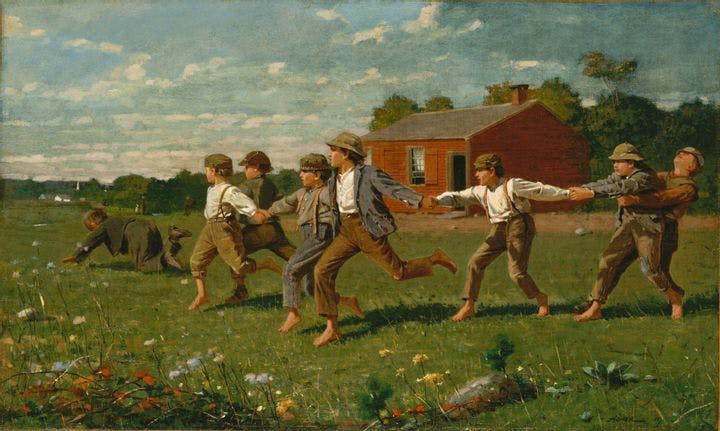

A history of children's play shows that it is anything but trivial.

Shortly after classes started this year, tag was banned from yet another playground, this one at an elementary school in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Chasing offended some sensibilities. In defending the decision, an administrator noted that only two parents had raised objections to the new rule. At a time when children’s play seems under siege, Howard Chudacoff ’s history—the first of its kind—arrives to tell us what we are letting slip away.

"Children have always cultivated their own underground of unstructured and self-structured play, which they did not often talk about with adults," says Chudacoff, a history professor at Brown. To peek into this private world, he has consulted dozens of diaries written by children, both historical and contemporary. Even in the Puritan America of the 1600s, when play was considered "the devil’s workshop," children slipped off and chased each other in the woods.

But for the past several decades play has been "colonized" by adults, who now firmly prefer indoor environments for their children or, if they must play outdoors, structured, supervised activities—think Little League, founded in 1939. It’s a travesty, Chudacoff suggests, to call "play" a pursuit in which adults push kids as young as eight to train so hard that they develop the overuse injuries found, until recently, only in professional athletes well along in their careers.

The "sheltered-child model" of childhood isn't new. As the urban middle class started to grow in the mid-19th century, so did the idea that children’s physical and emotional development should occur in a protected environment. In the 20th century, the idea gathered force through the writings of John Dewey and Sigmund Freud and the explosive growth of the toy industry, which today grosses $25 billion a year. But it was the onset of the polio epidemic in the early 1950s, Chudacoff says, that ushered in the age of hypervigilance. From then on, "professionals fixated on safeguarding youngsters from every possible hazard," both real and imagined.

Probably because children not so long ago did enjoy unstructured and improvised play, the mere mention of the word tends to conjure sweet memories of childhood among adults. Not in Chudacoff. He is constantly wiping sentimentality off the spectacles of those writers—from Edward Everett Hale to Annie Dillard to ordinary mortals—whose descriptions of their own childhoods in letters, autobiographies, and diaries he draws on. While Dillard describes halcyon days when her parents fostered her talents and supervised her activities, she also writes that there were times when they did not "get involved with my detective work, nor hear about my reading, nor inquire about my homework." Dillard may emphasize her parents’ nurturing, but "her freedom to pursue her own curiosity was undoubtedly achieved by escaping the ‘supervised hours,’ " Chudacoff drily notes.

The beauty of genuine play is that it reflects the world as kids—rather than adults—see it. Through play, children not only develop their own culture but learn what they can and can’t do by taking risks. This, neuroscientists and other researchers tell us, is what helps prepare children for adulthood. Play fosters decision making, memory and thinking, speed and flexibility of mental processing. Play makes brains nimble, capable of adapting to a rapidly evolving world.

Yet play is the very thing that today’s adults sacrifice to their anxieties about their children’s futures. It’s their own emotional need, however, that parents are heeding when they overprotect their children even as they push them to the point of injury on the ball field: success, success, success. Chudacoff finds particularly worrisome children’s seeming acceptance of these adult incursions on their autonomy, when kids before them were never so complacent.

But he’s too smart to be entirely bleak. Yes, today the very important underground of children’s play—removed from watchful adult eyes—is rare outdoors and seldom involves spontaneous groups of neighborhood kids and schoolmates. But it can be found indoors—mostly in kids’ engagement with video and computer games. Adults rail about video games to the extent that the grownups haven’t managed to completely domesticate children’s play. "In their seclusion, children are partaking of a kind of autonomy, one that consumer society has expanded for them," Chudacoff writes.

His history demonstrates that the topic of play is anything but trivial. And by showing us where we've been, he can help us decide where, as a culture, we want to go.

* * *

Reviewed: "Children at Play: An American History" by Howard P. Chudacoff, New York University Press, 2007.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons