Fall 2008

Saints and Sinners

– T. R. Reid

T. R. Reid reviews a "warts-and-all history of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, one of the darkest moments in the 180-year history of the Mormon Church."

If history is written by the victors, church history is usually written by the vicars. Naturally, these captive chronicles—generally churned out by priests, bishops, and in-house archivists—tend to accentuate the positive and gloss over errors and excesses.

So it is both surprising and admirable that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints provided extensive official support to a new warts-and-all history of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, one of the darkest moments in the 180-year history of the Mormon Church. The church opened century-old archives for this account of the infamous mass murder in a high Utah meadow in 1857.

The church was not always so helpful. For nearly a century after some 120 California-bound emigrants were killed by local Mormons, church leaders relied on the stonewall. As late as 1990, when a memorial was unveiled at the massacre site—at the foot of the Mormon Range, in the desert corner where Utah, Nevada, and Arizona meet—descendants of the victims complained that the church was still concealing basic information about the crime.

Massacre at Mountain Meadows is not a formal Mormon publication, but its authors include an assistant church historian (Richard E. Turley Jr.) and a former director of the church’s Museum of Church History and Art (Glen M. Leonard). Ronald W. Walker is an independent historian and a writer of Mormon history.

Their unparalleled archival access has not produced any major new conclusions. But in addition to a thorough account of the state of the Mormon Church and the Utah Territory in 1857, this volume contains the most information yet published on the individual militiamen, the individual victims, and the 17 babies and children whose lives were spared in the melee.

In the summer of 1857, the Mormons in the Salt Lake valley were celebrating the 10th anniversary of their arrival in Utah after an arduous westward trek to escape religious persecution. But their leader, Brigham Young, was terrified by the news that a U.S. Army expedition was making its way toward Utah. Unless the Mormons and their Indian neighbors were willing to fight, Young said, “the United States will kill us both.”

The Mormons’ sense that “the United States” was their bitter enemy is one of the most striking facts illuminated by this history. The Mormon Church is an intensely American religion. It was founded in 1830 by a New York farmer named Joseph Smith, and its scripture places the Garden of Eden in Missouri and relates how a resurrected Jesus appeared and preached to American Indians. When the Mormon pioneers settled in Utah, Young himself was appointed the territory’s first governor.

Mutual fear and loathing occasionally flared into battles between Mormon settlers and "overlanders" who crossed their lands heading for California.

By 1857, though, the Mormons wanted nothing to do with the U.S.A., while most Americans saw the polygamous sect as a dangerous cult. The mutual fear and loathing occasionally flared into battles between Mormon settlers and the thousands of “overlanders” who crossed the Great Basin trails each summer in wagon trains headed for California.

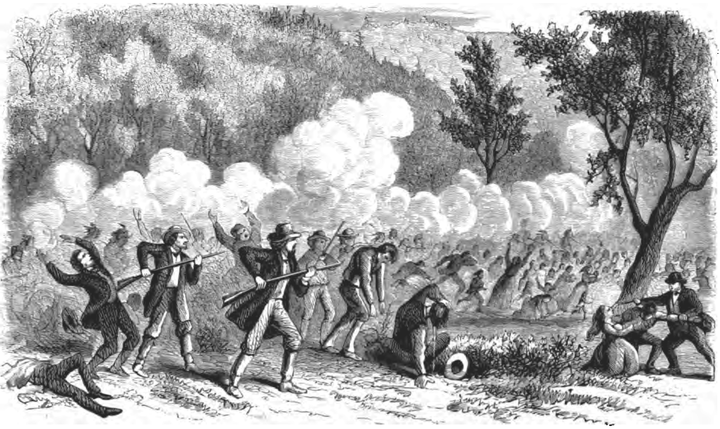

In late summer, nearly 140 emigrants from Arkansas and Missouri—two states where Mormons had faced particularly bitter enmity—encamped at the Mountain Meadows. The local Mormon militia devised a plan to annihilate the whole party—men, women, and children—and place the blame on Indians. The local Paiutes trusted the Mormons (they referred to church president Brigham Young as “Big Um”), and some Indians did take part in the killing. But the authors make it clear that the Mormons designed the “improbably sinister” plan of attack: Under flag of truce, the white men convinced the emigrants to put away their weapons, then led them down the trail to a bloody ambush.

The authors conclude that Young did not know about the planned attack in advance, but he did know the truth afterward, while his church pointed fingers at everybody else. In their view, Young and other church leaders were responsible for the general climate of fear and open hostility to emigrants that drove the local militia to “set aside principles of their faith to commit an atrocity.”

Except for Mountain Meadows addicts (and there are a lot of them, both Mormon and otherwise), this history is likely to disappoint. Other than a sketchy “epilogue” about the execution of one militia leader, John D. Lee, the book says nothing about the aftermath of the murders. A reader who cares to know how news of the massacre became public, how the church managed its long cover-up, and what happened to the perpetrators other than Lee will be left high and dry.

For those who are new to this historical episode, Juanita Brooks’s well-known 1950 chronicle The Mountain Meadows Massacre or Will Bagley’s Blood of the Prophets (2002) might be more satisfying. But for people already familiar with the sordid tale, or for readers who like their history awash in carefully documented detail, this history may be a useful addition to the library.

* * *

T. R. Reid has covered the Rocky Mountain West and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for The Washington Post and National Public Radio. He is the author of several books, including We’re Number 37! which is forthcoming next year.

Reviewed: Massacre at Mountain Meadows by Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley, Jr., and Glen M. Leonard, Oxford University Press, 430 pp, 2011.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons