Fall 2010

Tortured Artist

– Steven Biel

The art, like the artist, was solid, straightforward, and robustly American.

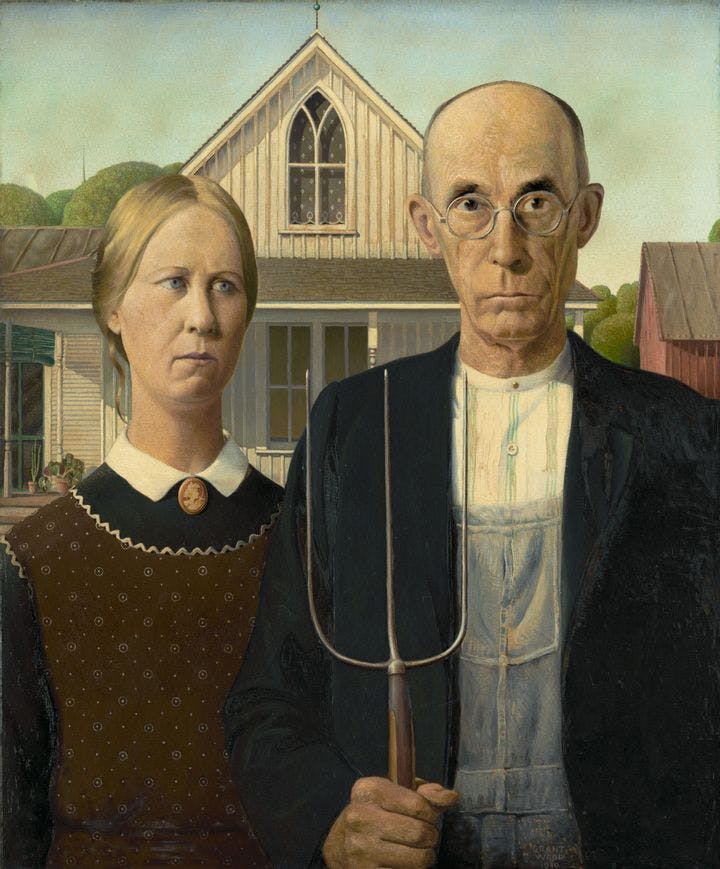

Grant Wood’s life story, as he told it to the press and as many of his biographers have repeated it, went like this: Born in rural Iowa in 1891, Wood showed artistic precocity from an early age, flirted with bohemianism, turned his back on his benighted region under the sway of H. L. Mencken, traveled to France, grew a hideous beard, produced derivative Impressionist paintings, returned home, shaved off the beard, discovered a “native” subject matter and style (most famously in his 1930 painting American Gothic), and became America’s “artist in overalls.” Well adjusted, hard working, and clean living, the mature Wood was everything the stereotypical artist wasn’t. Most of all, he was masculine—“a sturdy, foursquare son of the Middle West,” as an admiring critic put it. The art, like the artist, was solid, straightforward, and robustly American.

In Grant Wood: A Life, R. Tripp Evans, an art historian at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, reveals how this narrative of “normalcy” hid in plain sight the reality that Wood was a closeted homosexual. Newspapers and magazines routinely remarked on his apparently permanent bachelorhood. In 1940, some of Wood’s colleagues at the University of Iowa tried to have him fired for, among other transgressions, his alleged homosexual relationship with his secretary, the latest in a series of young male protégés and companions. Faced with constant threats of exposure, he sought protection in his regular-guy persona, to the point of ratifying the virulent homophobia of his friend and fellow Midwestern regionalist Thomas Hart Benton, whose 1937 autobiography he praised for its “healthful commentary” on “the parasites and hangers-on of art . . . with their ivory-tower hysterias and frequent homosexuality.”

Evans gives us a moving and persuasive psychoanalytic study that finds in both the life and the work powerful forces of “desire, memory, and dread.” The artist’s father, who died suddenly when Wood was 10, looms large throughout. Stern and intimidating, Maryville Wood compared Grant unfavorably to his two brothers, disapproved of his unmanly artistic inclinations, and left him with “a sense of shame” about “his artwork and its attendant sense of fantasy.” The doting and adored mother, Hattie, completed “the family romance that would shape so much of Wood’s life and work.” Wood lived for most of his adult life with his mother and his younger sister, Nan—his model for the woman in American Gothic—in a small carriage-house studio in Cedar Rapids. Taking care of Hattie served as his excuse for bachelorhood until the prospect of her death prodded him into a disastrous marriage, in 1935, to an older woman, Sara Sherman Maxon.

Pushing aside the public inspirations for and meanings of Wood’s work that have preoccupied critics since the 1930s, Evans explores “the personal factors that complicate everything we may think we know about his paintings,” including American Gothic, which displays “not the artist’s patriotism” or some conception of the national character “but a fractured return to his own past.” From ostensibly unimportant details—the female figure wears the Persephone brooch Wood gave to Hattie; the male figure wears Maryville Wood’s glasses rather than those of the model (the artist’s dentist)—Evans establishes the presence of the family romance in the painting. We immediately recognize that the woman’s gaze is directed away from us, but on closer examination so is the man’s. “In establishing this peculiar standoff between sitter and viewer,” Evans explains, “Wood deftly illustrates his own feelings of invisibility before his father”—feelings that Wood repeatedly articulated in his unfinished and unpublished autobiography, Return From Bohemia. In American Gothic’s complex invocation of the Persephone myth, Evans finds an artist who was far from reconciled to this return.

Late in the book, after an equally dazzling reading of Parson Weems’ Fable (1939), Wood’s last major painting before his death in 1942, Evans offers a sweeping defense of his method. Having claimed that the small figures in the background suggest “an incestuous union” between mother and son (to complement the “patricidal hatchet job” in the foreground), he addresses readers who might react with “alarm and disbelief” to this interpretation and those that precede it. Such reactions, Evans argues, would indicate not only a lack of sympathy with his approach but a “conscious resistance to the psyche’s raw and anarchic operations.” By treating any objection that an interpretation “goes too far” as a symptom of resistance, Evans precludes even sympathetic readers from reasonably identifying instances of overreaching. Why not leave potential critics to their opinions rather than preemptively psychoanalyze them?

No doubt there will be readers, whatever their motives, who see Grant Wood: A Life as a slander against the self-described “simple Middle Western farmer-painter” and his wholesome paintings. But Evans has done Wood a great service in saving him and his work from the one-dimensionality to which they have largely been consigned. He has rendered the artist and the art in all their ambivalence, disquiet, mischief, deceptiveness, and anguish. This is a deeply respectful and compassionate biography.

* * *

Steven Biel is executive director of the Humanities Center at Harvard and a senior lecturer on history and literature at Harvard University. His most recent book is American Gothic: A Life of America’s Most Famous Painting (2005).

Reviewed: Grant Wood: A Life by R. Tripp Evans, Knopf, 402 pp, 2010.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons