Summer 2017

Is Russia Going Hard or Soft in the Arctic?

– Alexander Sergunin

In contrast with the internationally widespread stereotype of Russia as a revisionist power in the Arctic, Moscow’s future actions in the region are more likely to be fairly pragmatic in nature.

Is Russia igniting a new arms race in the Far North or taking justifiable steps to defend its interests in a changing environment? The answer to that question depends greatly on whom you ask, where they are, and just how much they appreciate the range of issues that factor into Russia’s Arctic policy.

In the West, some analysts believe that Russia, due to economic weakness and technological backwardness, tends to privilege coercive military instruments to protect its interests in the Far North. Western mass media and, to a lesser extent, politicians portray the modernization programs and changes in Russia’s military capabilities within its Arctic territories as a possibly game-changing buildup that increases the risk of conflict. They often trace the start of their concerns to 2007, when Moscow resumed naval and air patrols in the Arctic and North Atlantic regions and planted a flag under the North Pole, staking a major land claim. The Ukraine crisis has only fed Western skepticism of Russia’s true aims.

Moscow insists that its intentions, as articulated in the Arctic doctrines of 2008 and 2013, are inward-focused or purely defensive, and aimed principally at the protection of the country’s legitimate interests. Primary among those interests, it says, is the development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation (AZRF), already a vital region for the national economy and one with great promise for further development in energy, mining, infrastructure, communications, and beyond. The Kremlin also maintains that it is not pursuing a revisionist policy, but rather wishes to resolve all disputes in the Arctic by peaceful means, relying on international law and organizations. Military strategists generally insist that the country must be prepared for contemporary and emerging security issues, no aggression implied.

Certain Russian actions and activities in the Arctic do support officials’ stated determination to stick to a soft-power approach, in a context of dialogue and diplomacy. At the same time, the cold, hard facts of increasing military assets in the Russian Arctic suggest that the government is making sure it is well prepared to flex its northern muscle. When the balance sheet is tallied, there are grounds to believe that Moscow will pursue fairly pragmatic and responsible policies in the region for the foreseeable future.

Russia's Arctic Economy

Between the collapse of the Soviet Union and the early 2000s, the Kremlin paid little attention to the North. The end of the Cold War meant that the region was no longer a zone of possible confrontation with NATO and the U.S. In the Yeltsin era, the economic potential of the region was underestimated, and Russia's northern reaches were perceived by the federal government as a burdensome source of socio-economic problems. Almost abandoned by Moscow, these areas had to rely on themselves (or foreign assistance) for survival. Things began to slowly change when the general socio-economic situation in Russia improved, and the Putin government, with its ambitious agenda of national revival, came to power.

The industrial base in the AZRF currently accounts for up to 20 percent of the entire Russian GDP – even if only about 1.6 percent of the country’s population lives there.

Today, Russia has enormous national interests in the Arctic region. The industrial base in the AZRF currently accounts for up to 20 percent of the entire Russian GDP – even if only about 1.6 percent of the country’s population lives there – and nearly a quarter of Russia’s export revenues. Fueling these figures is the fact that the region produces no less than 95 percent of the country’s gas and approximately 70 percent of its oil. Russian geologists have discovered some 200 oil and gas deposits and there are more than 20 large shelf deposits in the Barents and Kara Seas which are expected to be developed when prices rise. The AZRF’s mining industries yield 99 percent of Russia’s diamonds, 98 percent of its platinum, and the majority of other rare metals. Reduced ice coverage due to global warming will mean increasing access to these natural resources and correspondingly increasing significance for the AZRF. The Russian federal and regional governments, along with the private sector, have articulated plans to further develop the industries and infrastructure of the region, including hundreds of billions of dollars in Russian and foreign direct investment in energy, mining, transport, and communications.

Moreover, as the Arctic’s sea ice coverage continues to drop, Russia stands to earn considerable economic benefits from the development of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) – which, when navigable, is the shortest shipping route between European and East Asian ports. Important domestic routes connecting the full length of the country’s enormous northern border should also expand. Moscow believes that by improving NSR infrastructure and safety, the NSR will be attractive not only to Russian business, but also to foreign shipping companies. When the eagerly anticipated Yamal liquefied natural gas plant becomes operational next year, shipments to East Asian markets, and potentially to Europe and North America, will be facilitated. In a sign of more to come, the new Christophe de Margerie gas tanker made it through the NSR in August 2017, becoming the first ship of this type to do so without needing an icebreaker escort.

With this vast commercial potential as a backdrop, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced that two new Arctic coast defense divisions are to be established by 2018 as part of an effort to strengthen security along the NSR. One is likely to be stationed on the Kola Peninsula, in addition to existing military units there, while the other will be in the eastern Arctic. The new forces can cover anti-assault, anti-sabotage, and anti-aircraft defensive needs. Given the trend of increasing Arctic access, the government has also made strengthening the Border Guard Service a top priority for High North security. The Border Guard has been assigned to deal with new soft security threats and challenges, such as the establishment of reliable border-control systems, the introduction of special visa regulations to certain regions, and the implementation of technological controls over fluvial zones and sites along the NSR. All in all, Moscow plans to build 20 border guard stations along its Arctic Ocean coastline.

On these fronts, the deployment of new assets and the expansion of security mandates in the Russian Arctic appear to be reasonable and practical steps to support Russia’s plans for developing the region.

Another change is the ongoing reorganization of the Russian Coast Guard, a part of the Border Guard Service, which now has a wide remit in the Arctic; in addition to the traditional protection of biological resources in the Arctic Ocean, oil and gas installations and shipping along the NSR are among the agency’s new priorities. The attention that Russia is now paying to the Coast Guard is in line with what other coastal states do, especially Norway and Denmark. Moreover, Russia actively partook in the creation of an Arctic Coast Guard Forum, which was established by the coastal states in November 2015. On these fronts, the deployment of new assets and the expansion of security mandates in the Russian Arctic appear to be reasonable and practical steps to support Russia’s plans for developing the region.

Underwater Outpost

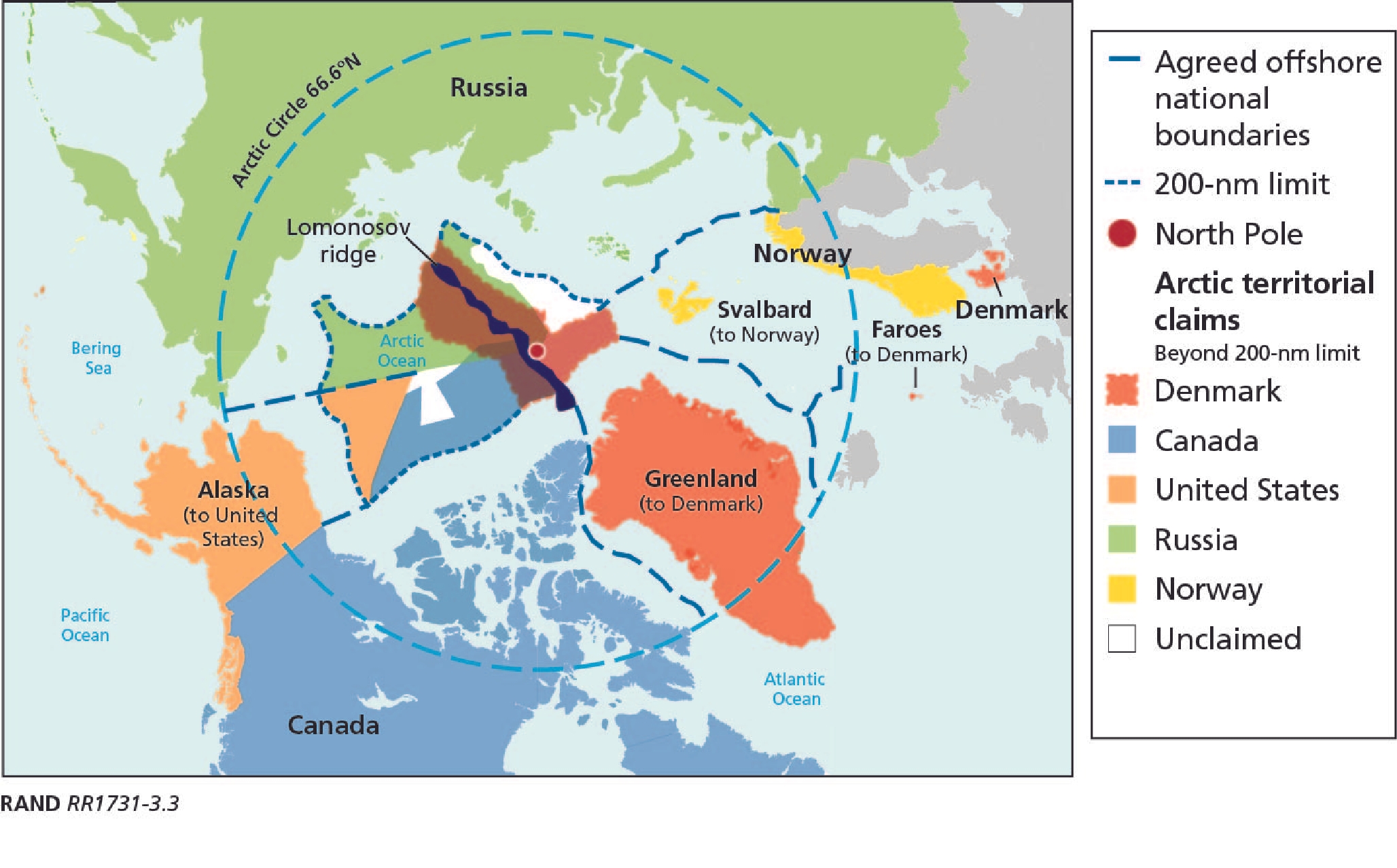

Beyond guarding the AZRF and facilitating its development, a central priority of the Kremlin’s regional strategy is to cement its claim to a vast expanse of Arctic Ocean territory. In its initial claim in 2001, Russia argued that the Lomonosov Ridge and the Alpha-Mendeleev Ridge are both geological extensions of its continental Siberian shelf and, as such, that much of the central Arctic Ocean falls under its jurisdiction. The UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) found the substantiation of the claim to be insufficient and requested more information. In 2007, Moscow chose a highly public way to show that it was undeterred: two mini submarines completed a record-breaking descent of more than two and a half miles beneath the North Pole and planted a titanium Russian flag in the seabed. The move was not received warmly in the West.

Despite lingering characterizations by some of the flag-planting incident as an attempted land-grab, the Kremlin has insisted that it plans to solve the problem within the framework of international law, peacefully and based on solid data. Russia resubmitted its application in August 2015, and the CLCS started its review the following year. The new claim included underwater territories with a total area of almost twice the size of Texas. The area holds an estimated 4.9 billion metric tons of standard fuel. Parts of the Russian claim overlap with Danish and Canadian claims, and the result of the review process remains to be seen. In principle, the “cooperative/compromise scenario,” which was discussed between Canada, Denmark, and Russia prior to the Ukraine crisis, is still one of the possible outcomes. The CLCS could encourage the three contenders to negotiate an agreement which could include the idea of making the central Arctic a zone of international cooperation and/or a natural reserve governed by the UN.

Ukraine in the Arctic?

Today, many western concerns about Russia’s Arctic intentions make direct reference to the Ukraine crisis, or rather, how the West views Russia’s actions and intentions in Ukraine. The crisis, however, had little impact on Moscow’s perception of the Arctic as a region of international cooperation and peace. As before, Russia’s military strategy has three major goals: first, to demonstrate sovereignty over the AZRF, including its offshore exclusive economic zone and continental shelf; second, to protect its economic interests in the High North; and third, to demonstrate that Russia retains its great power status and has world-class military capabilities. It should be noted that following the Soviet era, the Russian military presence in the Arctic had degenerated significantly, and the country’s nuclear and conventional forces badly needed modernization. In this sense, Russia’s strategy is comparable with those of other coastal states; the U.S. and Canada, for example, are modernizing their assets in the Arctic as well.

The modernization program for Russia’s strategic forces in the North includes the renewal of its nuclear submarine fleet. This program was planned ten years ago, and it was neither initiated nor affected by the Ukraine crisis. Currently, six Delta IV- and one Typhoon-class submarines are being updated. Future plans would replace these watercrafts with the new Borey-class, fourth-generation, nuclear-powered, ballistic missile submarines.

In contrast with the strategic component, the composition of Russia’s conventional forces in the Arctic was affected by Ukraine.

At the same time, some Russian security brass do believe there are threats and challenges that require further development of military capacity in the Far North. They took notice of the negative effect of the Ukraine crisis on Russia’s relations with NATO and its member states, which unilaterally suspended several cooperative projects with Russia, including on the development of the Russian energy sector in the Far North, the development of confidence- and security-building measures, and military-to-military contacts. As such, in contrast with the strategic component, the composition of Russia’s conventional forces in the Arctic was affected by Ukraine.

Plans had previously been announced to transform the motorized infantry and marine brigades located in the Murmansk region, near Norway, into an Arctic special forces brigade, with soldiers trained for operations in the Far North. It had also been decided that all conventional forces in the AZRF should form an Arctic Group of Forces, to be led by a Joint Strategic Command “North” (planned for 2017). However, due to tensions between Russia and the West resulting from the Ukraine crisis, the Arctic brigade was created ahead of schedule, in January 2015, and deployed in Alakurtti, close to the Finnish border. This was done to augment, rather than to replace, the existing brigades – in contrast with initial plans. It was also announced that a second Arctic brigade will be formed and stationed east of the Urals. Given the “increased NATO military threat” in the Arctic, President Putin decided to accelerate the creation of Command “North” as well. It was established in December 2014, three years ahead of schedule.

While these developments may sound alarming to some, there is only a rather limited level of modernization and increases or changes in force levels and structures. Some of these changes – the creation of new special forces and border guard units, the commissioning of more sophisticated warships and air defense systems, and the establishment of new command structures – have little to do with obtaining new offensive capabilities or power-projection into disputed areas or the region at large. Rather, they are for the patrolling and protecting of undisputed national territories and exclusive economic zones that are becoming more accessible, including for illegal activities, such as poaching, smuggling, and uncontrolled migration. Other changes – such as the modernization of the Russian strategic nuclear submarine fleet – may have more to do with maintaining a deterrent potential against NATO or the U.S. rather than with developing first-strike potential and other offensive capabilities. To put it differently, these modernization programs should not provoke an arms race or undermine regional cooperation.

More than Military

Moscow must also tackle the serious social and economic problems of the country’s indigenous Arctic communities, including the incompatibility of their traditional ways of life with present economic realities; rising disease rates; high infant mortality; and alcoholism. Unemployment among Russia’s indigenous peoples has been estimated at between 30 and 60 percent, three to four times higher than that of other AZRF residents. Life expectancy is 49 years, compared to 72 for the average Russian. Moscow’s efforts to remedy these ills have still not come close to its targets and are harshly criticized by indigenous peoples and both national and international human rights organizations. The quality of life for the indigenous population in regions such as Khanty-Mansi, Nenets, Koryakia, and Chukotka remains unacceptably low. The Yamalo-Nenets area, perhaps exceptionally, has a booming indigenous economy built around reindeer-herding, with social programs implemented effectively and major conflicts between indigenous interests and energy companies generally avoided.

The Kremlin does appear to understand the need for constructive dialogue and deeper engagement with all of Russia’s AZRF regions, municipalities, indigenous peoples, and NGOs. In practice, however, the federal bureaucracy’s policies and approaches will often confront subnational actors and civil society. Instead of using the resources of these actors in a creative way, Moscow tries to control them. In so doing, the state undermines their initiative, making them passive, both domestically and internationally.

Russia’s Arctic policy attempts to address all of these factors, from the economic to the territorial, from the geopolitical to the social. In contrast with the internationally widespread stereotype of Russia as a revisionist power in the Arctic, its future actions are more likely to be fairly pragmatic in nature. This is far from a worst-case scenario. On the one hand, such an approach will aim to protect Russia’s legitimate economic and political interests in the High North. On the other hand, Moscow can benefit from cooperation with foreign partners in exploiting the Arctic’s natural resources, developing its sea routes, and advancing environmental research and protection. Russia clearly has a preference for soft power – or, more precisely, non-hard power – instruments in the Arctic theatre. That includes a conspicuous disposition to dialogue and engagement through the relevant international organizations. This preference should be taken seriously by Russia’s partners, as reciprocation will be decisive in determining the future of the Arctic.

* * *

Alexander Sergunin is a professor of international relations at St. Petersburg State University and a scholar of Russian foreign policy. He is co-author of Russia in the Arctic: Hard or Soft Power?

Participants of the 2007 mission to the floor of the Arctic Ocean when two deep-diving Russian mini-submarines slipped beneath the ice at the North pole and descended more than 2 1/2 miles to the ocean floor on a Russian quest to claim much of the Arctic's oil-and-mineral wealth. AP Photo/Vladimir Chistyakov.