Summer 2020

Korean War: Open Questions

Historians examine what we still need to know about the so-called “Forgotten War.”

Scholarship is driven by open questions. What don’t we know? The Korean War is no exception.

Researchers have never stopped exploring the conflict, and the opening of new archives in the U.S., Europe, and Asia are helping them do it.

For our Summer 2020 issue, “Korea: 70 Years On,” we asked four distinguished historians to address what they see as the most important open questions about the war and its legacy.

Open Question: The Lived Experience of North Koreans in the War

The Korean War was experienced in different ways by different people. Much of the literature about the war in the United States focuses on the experiences of a relatively predictable set of actors: political and military leaders and U.S. combat forces. When bookstores and public libraries have any books on the Korean war at all, they tend to be military histories that are written from the American perspective. They focus primarily on U.S. strategic thinking or the combat experience of American forces.

While the new international history of the war that developed in the 1990s expanded on this perspective by incorporating the communist world, much of it was still focused on political elites – Mao Zedong, Joseph Stalin and the like. Missing from these elite-driven histories is a sense of the war’s traumatizing impact on those who felt it most viscerally: the Korean people.

For three years, the Korean War turned the entire Korean peninsula into a ghastly war zone. Millions perished and violence was endemic. The waves of retaliation and counter retaliation carried out by leftist and rightist partisans in many areas rent the fabric of Korean society so badly that it took decades to recover. Even those who survived had their lives shattered, their property destroyed, and their opportunities narrowed. Historians have been far slower to turn their attention to these more human dimensions of the war.

Even those who survived had their lives shattered, their property destroyed, and their opportunities narrowed. Historians have been far slower to turn their attention to these more human dimensions of the war

Scholars have done a little better when it comes to the war’s impact on South Korea. We now have a limited understanding of how the presence of massive numbers of UN forces, the transition to a wartime economy, and the political chaos caused by the fall and recapture of cities and villages permanently changed life in South Korea. Our understanding of these phenomenon is still insufficient, but it is growing nonetheless as the most recent generation of historians finds new sources and tests different theoretical approaches.

The lived experience of war in the North has been almost completely neglected. When Americans pay attention to wartime North Korea at all, they mostly see a place where their armies slaughtered – and were slaughtered by – a ferocious and evil adversary, and a landscape in which major cities were transformed into ashes and rubble by relentless aerial bombing.

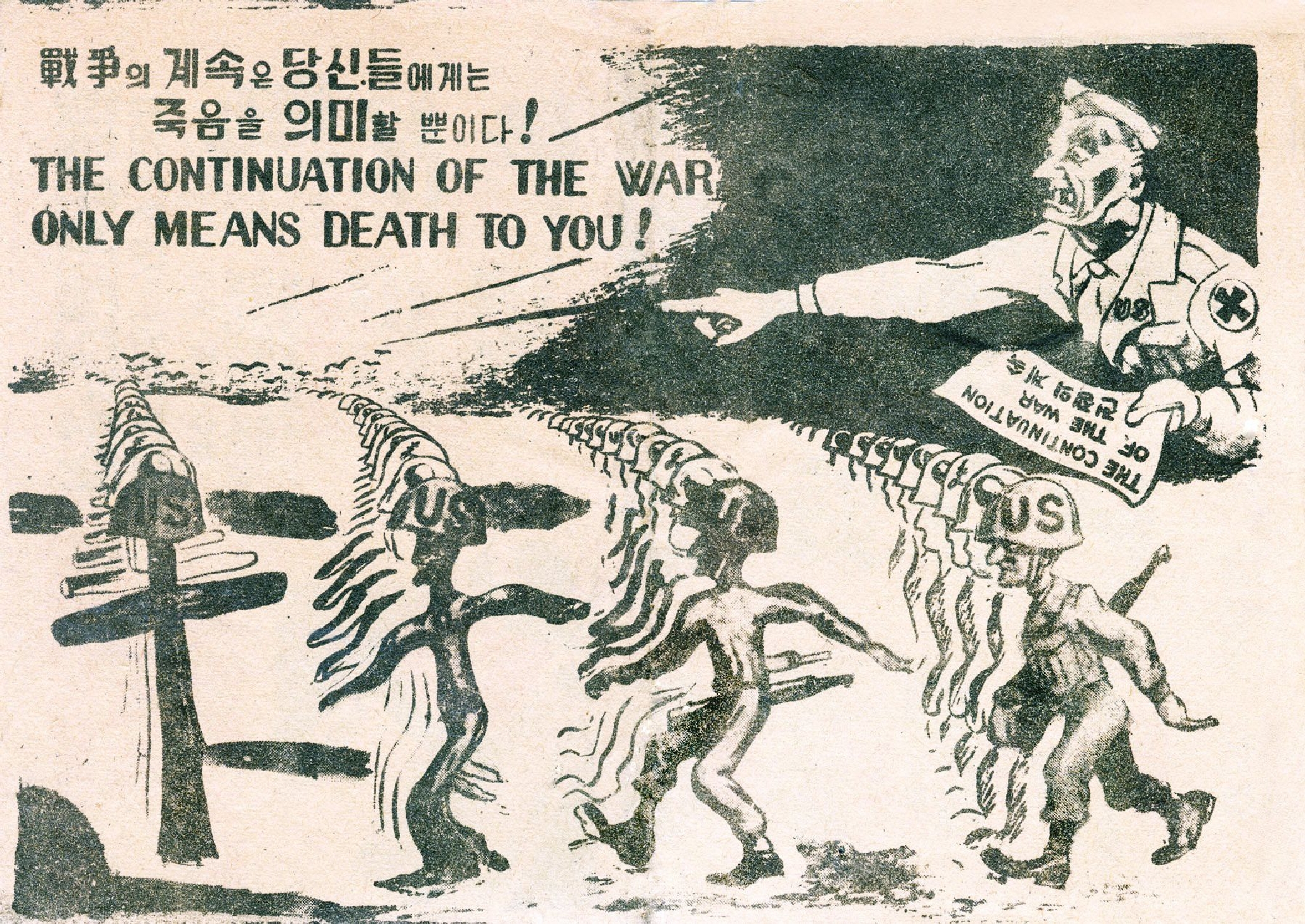

Americans don’t see it as a place where real human beings struggled for survival, mourned the loss of family members, and suffered permanent trauma because of the three years that they spent living under constant fear of death. And they care little about the social or cultural history of the war there. As a result, we know about the massive bombing campaigns carried out by American fighter planes and wartime atrocities committed by South Korean forces in North Korea. Yet we don’t understand much about their real human impact.

When it comes to everyday life in North Korea during the Korean War, there are many basic questions that are still unanswered: How did North Koreans learn to cope with the violence and loss that surrounded them? How did they see their own leaders, their obligations to their country, and the demands of military service? What were social relations between North Koreans and the hundreds of thousands of Chinese Volunteers who crossed the Yalu to fight alongside them like? There is scarcely a single book in the English language that takes any of these questions as its main point of departure.

Historians urgently need to start asking these questions. Contemporary North Korea cannot be understood without first understanding the complete suspension of everything that was considered normal there during the war. One of the reasons that, seventy years later, the Korean War has still not officially ended is Americans don’t realize how these experiences hardened North Korean hatred and mistrust of the United States.

For Americans who take media representations of North Korea as a bizarre rogue state at face value, Pyongyang’s unyielding commitment to its nuclear program seems hostile and irrational. But in North Korea, where the war is critical to the state’s raison d’être, the suffering that it caused remains a critical part of the society’s collective historical memory – and colors how North Koreans and their leaders see almost every issue. A powerful military is seen first and foremost not as a way of threatening neighbors, but as a way of preventing the horrors that were visited on North Korea seventy years ago from happening again.

None of this is to say that North Koreans were innocent victims during the Korean War, or that they did not commit an ample number of their own atrocities in South Korea. The evidence that it was Kim Il Sung who turned a smoldering civil war into a full-scale international conflict is undisputable, as is the evidence of the terror inflicted on South Korea by DPRK forces during the summer of 1950.

But this does not mean we should not recognize the basic humanity of our former adversary. If we do not do so, the Korean War might never end, and could even be reignited.

Gregg A. Brazinsky is professor of history and international affairs at the George Washington University. He is the author of Winning the Third World: Sino-American Rivalry during the Cold War and Nation Building in South Korea: Korean, Americans, and the Making of a Democracy. Follow him on Twitter @GBrazinsky.

Open Question: The “Long Peace” Between America and China

One of the great open questions about the Korean War regards what did not happen after the armistice was signed in July 1953.

In retrospect, it is almost miraculous that another Korea-style direct military confrontation between China and the United States did not happen for almost two decades following the end of the conflict. The possibility of such a confrontation was virtually eliminated only by the Chinese-American rapprochement in the early 1970s.

This Chinese-American “long peace” has been largely ignored by scholars of Chinese-American relations. Yet the absence of a war between China and America in the wake of the Korean War should in no circumstances be taken for granted.

Throughout the 1950s and the 1960s, China and the United States regarded each other as a mortal enemy. For Beijing, “imperialist America” was China’s number one foe, serving as a principal justification of its support to revolutionary insurgences in East Asia. This animus was also the main source of Mao Zedong’s excessive domestic mobilization, which culminated in such disastrous Maoist programs as the Great Leap Forward and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

For Washington, Communist China, compared with the Soviet Union, was a “more daring, therefore, more dangerous enemy.” Although the emphasis of America’s global Cold War strategy lay in Europe, and the Soviet Union was America’s presumed primary enemy, a large portion of America’s resources also were deployed in East Asia to cope with the “Chinese communist threats” there.

It is no surprise, then, that at several critical moments of tension in the wake of the Korean War, China and the United States could have easily slid into another Korea-style war – or an even more destructive conflict. Yet it was also the memory of Korea, as well as the lessons that Beijing and Washington had learned from it, that effectively prevented China and the United States from engaging in another direct military confrontation.

Vietnam is a case in point. In the spring and summer of 1954, it seemed the Vietnamese Communists, backed by China, would soon grasp victory in the First Indochina War. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower adopted the “domino theory” to describe Washington’s perception of the grave impact of allowing communist revolutions following the Chinese model to spread unchecked in East Asia.

Chinese policymakers noted Washington’s warnings. The Chinese repeatedly called their Vietnamese comrades’ attention to the danger of a “direct American intervention.” At a crucial meeting with Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nyugen Giap in early July 1954, Zhou Enlai spent many long hours beseeching the Vietnamese to abandon their pursuit of “total victory” in the war.

“We must remember the lessons of Korea,” Zhou emphasized, “the most important is to avoid an American intervention.” Ho and Giap accepted Zhou’s advice, opening the door to the Geneva Peace Accord on Indochina.

In retrospect, it is almost miraculous that another Korea-style direct military confrontation between China and the United States did not happen for almost two decades following the end of the conflict.

In the Taiwan Straits crises of 1958, China and the United States once again faced the grim prospect of a direct military showdown. Both sides showed restraint. When the Chinese artillery units shelled the Nationalist-controlled Jinmen islands, Mao emphatically ordered his frontal commander to ensure that “American ships would not be hit.” On the American side, U.S. warships tasked with protecting Nationalist convoys stayed beyond the range of the Chinese artillery, so as to avoid undesirable incidents.

In spring 1965, as the Vietnam War was rapidly escalating, both Chinese and American policymakers kept the lessons of Korea in their minds. Zhou and Chen Yi, China’s foreign minister, asked Pakistan and Britain to help deliver the following messages to President Lyndon B. Johnson: (I) China will not provoke war with the United States; (II) What China says counts; (III) China is prepared; and (IV) If the United States bombs China that would mean war and there would be no limits to it.

Zhou specifically mentioned that the Americans had failed to heed the warning message that he sent to Washington, via India, before China intervened in Korea. This time, China also changed the delivery channel, swapping a dubious intermediary for two staunch American geopolitical allies.

_underway_at_sea_on_16_August_1958.jpg)

Washington treated the Chinese warning signals seriously this time. From 1965 to 1969, China dispatched a total of 320,000 engineering and anti-aircraft troops to North Vietnam. Yet no Chinese combat troops were sent to Vietnam. U.S. ground forces did not invade North Vietnam, and aerial bombing of the North was confined to areas north of the 20th parallel, keeping a “safe distance” from Chinese borders. Another Chinese-American war indeed was avoided.

There was a sophisticated yet crucial reason for this which should be highlighted. Beijing and Washington regarded each other as enemies. But it seems that each side was willing to count on the consistent, “limited rationality” of the other to avoid another Korea-type war. There appeared to exist a critical “mutual confidence” of a certain kind in Beijing’s and Washington’s strategic thinking in the wake of Korea. Without acknowledging the legitimacy of the other side’s policy goals and ideological commitments, leaders of both countries nevertheless held a degree of faith in the other side’s willingness and capacity to persist in a limited and pragmatic course of action in accordance with its own rationale, logic and perceived interests.

Beijing’s international strategies and policies, upon examination, reflect a specific truth: In spite of its aggressive rhetoric and behavior, Mao's China was not an expansionist power as the term is typically defined in Western strategic discourse. Though it did use force, Beijing’s aim was not direct control of foreign territory or resources. Rather, China sought the spread of its revolution's influence to "hearts and minds" around the world. It was this aspiration for "centrality," rather than the pursuit of "dominance," that characterized the foreign policy of Mao's China.

The factors I describe above not only led to a “long peace.” They also present important implications for understanding China's external behavior then, now, and in the future. They merit closer examination and further study.

Chen Jian is Distinguished Global Network Professor of History at NYU-Shanghai and NYU. He is also Hu Shih Professor of History Emeritus at Cornell University. He is nearing completion of a major biography of Zhou Enlai.

Open Question: The Lasting Legacies of Korean War Special Operations

The failure rate of the missions was shocking, the full scope of which we still do not know because the records are incomplete, lost or remain inaccessible. In a literal sense, the history of Special Operations in Korea is truly the forgotten part of the Forgotten War. Thousands of Koreans – we do not know the actual number – never returned from their suicidal missions behind enemy lines in North Korea during the Korean War. Their courage and lives were expendable. But their sacrifices, and those of the Americans who led them, helped to restore U.S. unconventional and covert warfare capabilities that were almost completely eliminated after the Second World War.

The Korean War caught the United States with its proverbial pants down. The post-World War II demobilization precipitously reduced the Armed Forces by nearly 90 percent – from over 12 million to 1.5 million by June 1947. For many service personnel, the pace was too slow and demands for faster demobilization were backed with protests and demonstrations. The process, by necessity both political and social, was “willy-nilly,” and the consequences for military capability and readiness were devastating. In September 1946, the War Department estimated that the combat effectiveness was down to just 25 percent for all units in the Pacific. A 1952 Army study concluded, “When future scholars evaluate the history of the United States during the first-half of the twentieth century they will list World War II demobilization as one of the cardinal mistakes.”

A little noticed loss in the demobilization was the almost complete elimination of special operations units. World War II had spawned a plethora of these organizations – famed units such as Army Rangers, Navy Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT), Marine Raiders, and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) – that accumulated an expertise paid for in blood. They conducted the kind of irregular, covert and clandestine activities known as special operations. These military activities were usually conducted behind enemy lines and ranged from intelligence collection and direct actions such as raids, sabotage, assassination, and kidnapping to guerilla warfare and psychological operations.

The landmark National Security Act of 1947, which reorganized how the U.S. would handle the foreign policy and military challenges of the Cold War, created the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to provide national-level strategic intelligence. The scope of its concerns was quickly expanded to include covert paramilitary operations of the kind conducted by wartime organizations.

A year later, the National Security Council decided that the CIA would be responsible for, among other things, covert propaganda, sabotage, and subversion operations to include guerilla warfare. The military initially endorsed the decision, but the outbreak of the Korean War changed all this. For one thing, General Douglas MacArthur’s Far East Command (FEC) quickly recognized the need for developing these capabilities itself. The war had served as an abrupt reminder that their elimination had been premature and unwise.

Thousands of Koreans – we do not know the actual number – never returned from their suicidal missions behind enemy lines in North Korea during the Korean War.

In June 1950, the military had minimal special operations capability, and the CIA, due to MacArthur’s personal animosity, only had a 3-person cell in Tokyo to cover all of East Asia. By January 1951, however, a multitude of ad-hoc organizations had sprung up under FEC, the Navy and Air Force components of FEC, Eighth U.S. Army in Korea (EUSAK), and the CIA, conducting covert intelligence collection, raids, sabotage, kidnapping, and guerilla operations as well as dropping millions of leaflets weekly and broadcasting around the clock over radio and loudspeakers.

Thousands of Korean agents and guerillas, recruited from anti-Communist North Korean refugees and led by Americans, were inserted into North Korea by land, air and sea. The operations continued and expanded as the war dragged on, exacting increasingly heavy casualties. This toll grew especially heavy after the frontlines had stabilized in the summer of 1951, and Communist forces tightened rear area security. Chinese and North Korean security was so effective that in the last two years of the war, nearly every parachute-inserted agent was killed or captured. By the time of the armistice in July 1953, thousands of Korean agents and guerillas had been sent into North Korea – and were never heard from again.

Aside from the danger, these operations suffered from deep systemic and structural dysfunction arising from competing interests and culture of the sponsoring organizations, as well as a lack of experience and expertise. The diffused organizations conducting operations could not get along and cooperate for the greater good. One attempt in late 1951 to bring a semblance of order to covert actions was badly botched and only worsened the strained relationships between competing interests. The result was duplication of effort and increased risk. It was not unusual to find an aircraft departing for North Korea with agents and guerillas from two or more units on uncoordinated missions.

Did special operations affect the course and outcome of the conflict? Tragically, most historians agree that the effort had only a marginal impact on the war. But something of long-term consequence did emerge from the adversity and dysfunction: a reconstitution of these capabilities.

A decade after the Korean War Armistice, covert operations and unconventional warfare became widely and deliberately utilized in the war in Vietnam. Special operations not only played a large role in that conflict but represented the initial U.S. response before conventional forces were even committed. Among these new post-Korean War capabilities included the creation of the Army Special Forces, the evolution of the Navy UDTs to become SEALs, and the refinement of CIA paramilitary capabilities. The continued evolution and expansion of special operations reached its pinnacle with the formation of the U.S. Special Operations Command in 1987 and its dominant role in the post-9/11 War on Terrorism.

The Korean War triggered a revival of U.S. special operations that has had a continuing and expanding legacy. The full story of the conflict’s special operations awaits the declassification and release of records, especially from the CIA and China. It is a story that will clarify the sacrifices of thousands of Koreans who vanished behind enemy lines and whose service to their country have only been recently recognized. It will also help us to appreciate the significance of the Korean War for understanding the unique history of Special Operations and its place within the broader field of U.S. military history.

Sheila Miyoshi Jager is Professor of East Asian Studies at Oberlin College. Her most recent book is Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea. She is finishing a new book project, The Other Great Game: The Opening of Korea and the Birth of Modern East Asia, 1876-1905, which is forthcoming from Harvard University Press.

Jiyul Kim is a retired U.S. Army officer with over 28 years of service. He is a Visiting Instructor of History at Oberlin College.

Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Jiyul Kim are collaborating on The Korean War: A New History, which is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.

Open Question: Memorials – Remembering an Unfinished War?

Historians have not yet written the final chapter of the Korean War, even as memorials to the never-ended conflict rise across the American landscape.

Often referred to as the “Forgotten War,” the Korean conflict of 1950 through 1953 was sandwiched between World War II of the “Greatest Generation” and the long tragic nightmare of Vietnam. However, the Korean War has never been forgotten by historians.

In recent decades, an avalanche of significant new studies has provided a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the war’s origins, conduct, and consequences. As the war continues, halted only by an uneasy armistice that has lasted for nearly seventy years, studies of the Korean War proliferate. Their profusion has been made possible, in part, by access to greater international materials made available to scholars by the newly-opened archives and the declassification of government documents.

Meanwhile, manuscripts, memoirs and oral histories of participants in the conflict continue to surface. These new primary sources present historians with a further appreciation of the complex and continuing struggle for dominance on the Korean peninsula.

Public memory provides an additional area of exploration for the study of the Korean War, and examining how wars are remembered in popular culture, museums, memorials, and historic sites, has increasingly attracted the attention of the scholarly community. Both remembrance, as well as the need to acknowledge the costs and ravages of war, have become an essential element of a national psyche. And in recent years, our nation has experienced a memory boom, whether dealing with international warfare of the early 20th century or the fragmentation of warfare since 1945. In the United States, memorials now tend to be more inclusive of ethnic and racial minorities who fought in these wars, and the service of women in conflict. They also tend to focus on the soldiers who saw combat, instead of great generals, or leading political figures. Furthermore, it is the veterans of these wars and their families who have taken the lead in advocating for these memorials, as well as in funding and creating them.

War memorials can provide a means to examine the long and complex process of establishing a collective memory. The Korean War is a remarkable example of how a nation's public memory of an event can be formed and reshaped over several decades in the midst of ever-changing international dynamics. The American public memory of the Korean War has been influenced by the nation’s subsequent experience of the Vietnam War experience, and the establishment of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The dramatic improvement in the image of the Republic of Korea – as well as its rising world status following the success of the 1988 Seoul Olympics – has also played a role. The sudden end of the Cold War, and South Korea’s emergence as a democracy and prosperous “Asian Tiger,” have led to a feeling that the “police action” in Korea had been worthwhile.

Both remembrance, as well as the need to acknowledge the costs and ravages of war, have become an essential element of a national psyche.

Initially, the creation of the Korean War Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. presented a set of unusual challenges to those involved in its long and contentious planning process. When the project began in the late 1980s, the Korean conflict remained highly unpopular, and also had been largely forgotten by an American public still recovering from the traumas of the Vietnam conflict. Furthermore, the U.S.-led intervention in Korea had never even been declared formally as a war – and the conflict has never officially ended.

A fractious process finally led to the dedication of a striking and popular monument in July 1995. Yet many critics, including the influential Korean War Veterans Association, remain unsatisfied by it. They have demanded a wall of remembrance that lists the names of those killed or missing in the conflict, similar to that which comprises the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. And just like the war in Korea, the Korean War Veterans Memorial remains unfinished and, ironically, depends on funding from South Korean sources.

Even before the Korean War Veterans Memorial was dedicated in Washington D.C., communities across the nation were establishing memorials to commemorate the experiences and the sacrifices of those who fought in the conflict. And like the monument on the National Mall, these numerous and diverse endeavors tell us much about those who are compelled to memorialize the war.

One learns from these efforts that the Korean War is now clearly understood by the American public as victory for the United States, the United Nations, and the Republic of Korea. It is also clear that the American public now sees the Republic of Korea as worth the sacrifice made to save it from a communist takeover, and the Korean-American community in the United States is viewed with respect and appreciation. This feeling appears to be largely reciprocated by the Republic of Korea and the Korean-American community, both of which have significantly participated in the funding planning and dedicating of local memorials.

The Korean War may not yet have reached its end. But the writing of its history, as well as the process of its memorialization, has sought to establish the conflict’s place in the pantheon of American wars.

Michael J. Devine is an Adjunct Professor of History at the University of Wyoming. From 2001 until his retirement in 2014, he served as director of the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library. He has twice been named a Senior Fulbright Lecturer to Korea (1995 and 2017-2018), and was the Houghton Freeman Professor of American History at the Johns Hopkins University-Nanjing University Graduate Center in 1998 and 1999. He is the author of John W. Foster: Politics and Diplomacy in the Imperial Era, 1877-1917 (1981), and the editor of Korea in War, Revolution and Peace: The Recollections of Horace G. Underwood (2001).

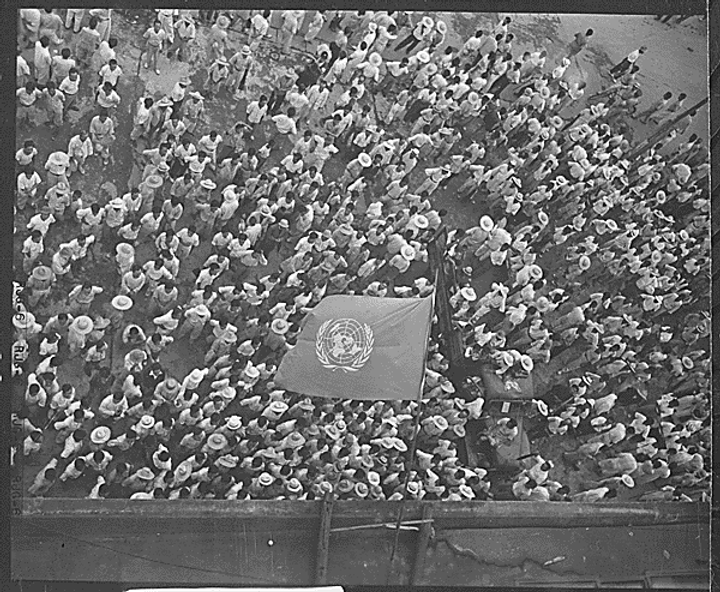

(Cover photograph: The UN flag waves over a crowd waiting to hear Syngman Rhee speak to the United Nations Council in Taegu, Korea on July 30, 1950. National Archives and Records Administration)