Spring 2016

Living on the New Frontier

– Zachary Laub

What happened when the United States hoped to build an urban idyll in Colombia?

On December 17, 1961, John F. Kennedy stood in an open field on the Andean plateau outside Bogotá, and laid the brick and mortar of what would be the cornerstone of a modest worker’s home. In his patrician New England accent, he spoke of the Alianza para el Progreso — the Alliance for Progress, his signature foreign aid program for Latin America. Around this pile of bricks would spring Ciudad Techo, a satellite city of the Colombian metropolis built from scratch on the site of a decommissioned airport.

The Alliance for Progress resembled a New Deal, projected abroad. It would entail large-scale, state-led interventions to spur economic growth and ensure for the peoples of the Americas the comforts of middle-class American consumer capitalism. “Those of us who love freedom realize that a man is not really free if he does not have a roof over his head, or if he cannot educate his children, or if he cannot find work, or if he cannot find security in his old age,” Kennedy said. In all, the United States committed more than $10 billion over 10 years to boost economic growth and social programs in Latin America.

Underlying Kennedy’s invocation of “freedom from want” was the acute fear of communist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. Fidel Castro had taken power in Cuba in February 1959. Just two weeks prior to Kennedy’s trip, Castro had declared himself a Marxist-Leninist, cementing Cuba’s ties to the Soviet Union. The frontlines of the Cold War had moved nearly to U.S. shores. “This is a battlefield,” Kennedy said as he laid the cornerstone of the first of what would be some 10,000 homes. In Latin America, the Cold War could be won or lost.

* * *

By the end of the 1950s, many U.S. policymakers saw Latin America as a powder keg. Mass media gave many of Latin America’s poor a glimpse of the luxuries of middle-class life just beyond their reach, compounding widespread indignation at the distribution of land and wealth. Political systems dominated by rural elites or the industrial bourgeoisie made prospects for social reform at the ballot box seem poor.

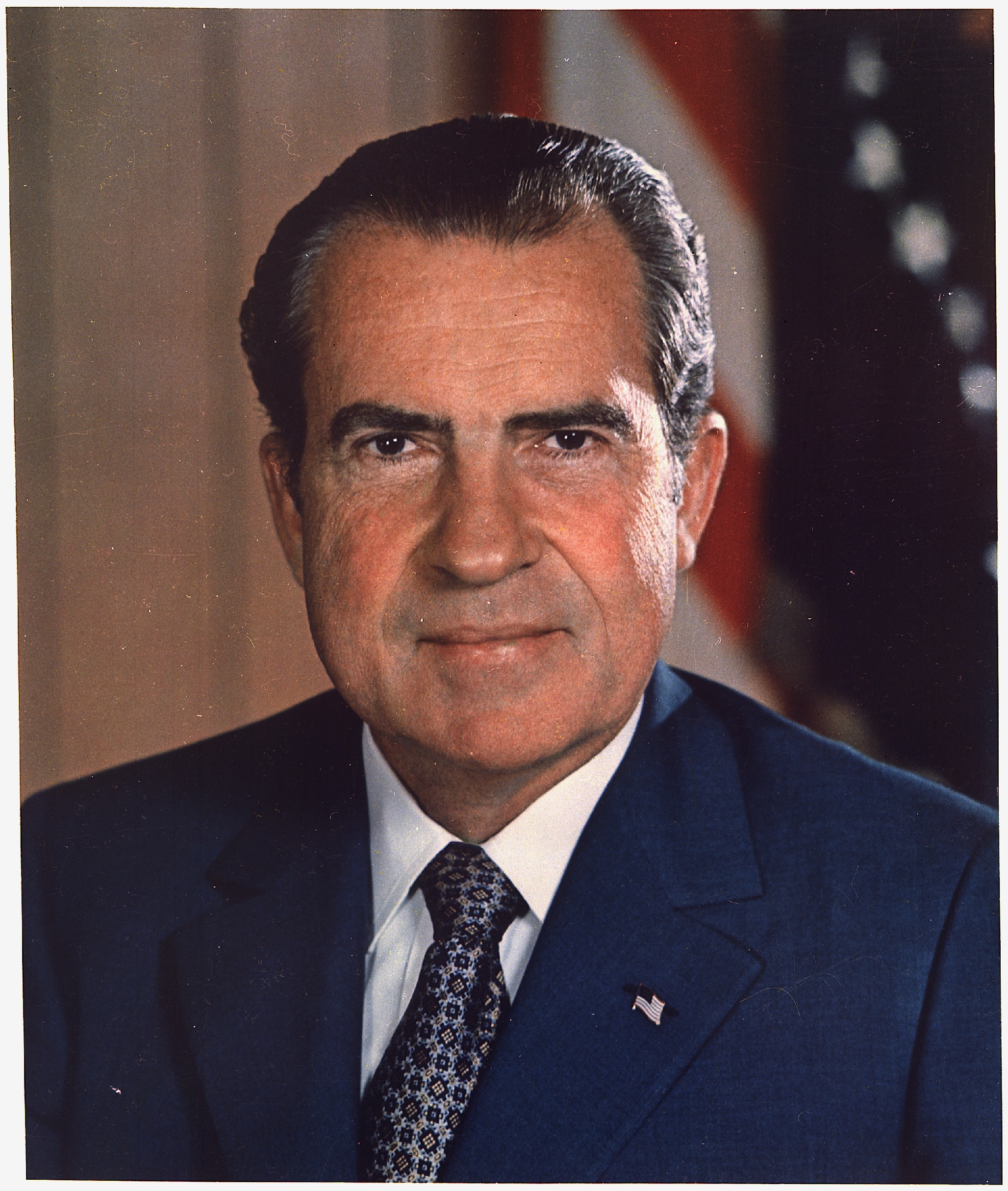

Some Latin American leaders may have stoked U.S. anxieties in their quest to secure a Marshall Plan of their own from the United States. Colombian president Alberto Lleras Camargo was among a generation of democratically elected liberal leaders who lobbied the United States for development financing by arguing that “underdevelopment,” in the parlance of the era, was at the root of much of the region’s turmoil. These pleas, however, went largely ignored until two events rattled the United States. In May 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower dispatched his vice president, Richard Nixon, on a goodwill tour of South America. In Caracas, mobs attacked Nixon’s motorcade. (In response, Eisenhower mobilized troops and naval support for a potential rescue operation dubbed “Operation Poor Richard.”) Fidel Castro’s guerillas entered Havana the following New Year’s Day, sending Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista fleeing. Concerned about unrest to the south, Eisenhower capitalized what would become the Inter-American Development Bank with $350 million, and Congress, for the first time, authorized $500 million in loans for social projects such as low-cost housing, primary education, and health care.

At the time, John F. Kennedy was a charismatic junior senator from Massachusetts with presidential aspirations. He charged the Eisenhower administration, including Nixon, the Republican candidate for president, with offering up the region to fidelismo through neglect. The loan fund, he said, was too little, too late. Compared with his Republican rivals, Kennedy’s ambitions were on a larger order of magnitude. He had imbibed theories of development championed by social scientists who advocated that short-term infusions of foreign assistance to “underdeveloped” countries could catalyze a virtuous cycle of economic growth and bring them to the level of affluence enjoyed by the postwar United States. Social reforms would ensure that the accruing wealth was spread widely, and elites who had stood in the way of past reforms would embrace them out of enlightened self-interest.

Kennedy characterized this program as a “middle-class revolution,” but it was anything but revolutionary. Rather, it was a technocratic program meant to undercut radical proposals by raising the living standards of rural peasants and the urban poor. Once these formerly impoverished groups had been given a stake in the status quo, they would be loath to support far-left political parties or communist guerrilla movements.

* * *

Colombia would be a testing ground and a showcase for U.S. efforts. In President Lleras, Kennedy had a likeminded counterpart. To qualify Colombia for U.S. funds, Lleras had by the end of 1961 proposed a land reform program and a 10-year development plan. With a large industrial base, U.S. policymakers believed, in the parlance of the era, that Colombia had the “preconditions for self-sustained growth.”

If Colombia’s potential was great, so too was its need. Land was concentrated in the hands of a small oligarchy. Reliance on coffee exports made the country vulnerable to swings in commodity prices. Schools were in short supply. As the rural population’s growth outpaced that of agricultural productivity, campesino families struggled to meet the rising cost of living. Violence exacerbated the hardship brought by economic stagnation in the countryside. In April 1948, the populist presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán was assassinated in Bogotá, setting off civil war known as La Violencia that was fought mostly in rural areas. Major cities offered opportunities to those fleeing rural poverty and violence, and the migration was immense: between Colombia’s national censuses in 1951 and 1964, Bogotá grew more than 6 percent a year, and anxious policymakers considered the urgent question: Where to house all the newcomers?

Ciudad Techo, planned by Colombia’s Land Credit Institute (Instituto de Crédito Territorial, or ICT) with Alliance financing, promised to chip away at the housing problem. For Kennedy, meanwhile, it would do more than just shelter Bogotá’s surplus population: he was eager to give Lleras a demonstrable success so that voters would support the incumbent National Front — a power-alternating arrangement between centrist liberals and conservatives — in the 1962 presidential election. The United States considered this arrangement vital to prevent La Violencia from escalating into a full-scale civil war. Kennedy also wanted to rally the support of other Latin American governments that were more eager to accept U.S. funds than to accept the reformist principles on which they were premised. And he most likely had a domestic audience as well: He had to demonstrate the program’s worth to Congress.

* * *

Most of Techo’s homes are two stories tall, and some have a haphazard third story stacked on top. They are canary yellow, lime green, silver with blue diamonds, and powder blue, and they line landscaped boulevards and snaking culs-de-sac, offering visual respite from the development’s surroundings: rows and rows of drab four- and five-story block apartment buildings that appear as if they extend all the way to the eastern cordillera on the horizon. The houses are all the same width, about three parking spaces across, except for a couple that have engulfed their neighbors. This uniformity belies their origins: Most of the original 10,000 houses were products of autoconstrucción — they were built by the beneficiaries of a lottery themselves, with neighbors and family members pitching in to improve or expand on the basic specifications over time, as families’ needs and resourced changed.

“A person couldn’t do it alone,” says Fabio Zambrano, a professor of urban history at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, “so self-construction implied I will help you, and you will help me.” This cooperation, he says, fostered a unique pride among those pioneering the new city, and strong social bonds. As an example of the resulting collective action and division of labor, he says that residents jury-rigged access in the 1980s to what was then a novelty: cable television.

Techo’s built-from-scratch origins made for tough circumstances early on. A critic writing in the Colombian architectural journal Escala in 1963 argued that the new city was clumsily planned. Housing density was distributed unevenly, with little relation to the small space allotted to parks, or to projected commercial centers. Superblocks restrict pedestrian circulation. The account suggests a city that is visually and culturally monotonous.

Compounding these design problems, commerce was scarce in the beginning, and Techo was isolated from both the nearby metropolis and the surrounding factories whose workers it was meant to serve. In their postmortem on the Alliance, written in 1970, former U.S. Agency for International Development official Jerome Levinson and New York Times reporter Juan de Onís wrote that some 200,000 residents of Ciudad Kennedy residents were largely stranded until 1969, when Bogotá’s mayor acquired a fleet of Soviet buses. Other Alliance housing projects, Levinson and de Onís write, faced similar obstacles. In Rio de Janeiro, favela residents were relocated far from the city center in the newly created Villa Alianza and Villa Kennedy. (The 2002 film City of God depicts the consequences of a similar slum-clearing enterprise.) Real-estate developers were the primary beneficiaries, while the favela resident’s had their livelihoods upturned.

In 1964, the ICT brought in new architects who considered aspects of Techo ill-conceived. They set to work on a next round of social housing that would be more responsive to its surroundings and variations among households. But the upside to Techo’s origins, Zambrano says, is that the social fabric that bound Techo’s original inhabitants insulated it from much of the violence that Bogotá experienced in the decades that followed its construction — even from that emanating from just across the highway in the Corabastos wholesale market.

* * *

Argenil Plazas was a poster child of the development; an early beneficiary of the project, he was later invited to the White House for a photo-op. The father of 17 was persecuted as the sole liberal in his Andean town, and fled with his family to the capital, his son told the newspaper El Tiempo in 2013. But most of the first families to live in Techo do not appear to have had a background like Don Argenil’s. Rather than the rural migrants and refugees and the urban poor that the Alliance was intended to target, the Techo lots went to mostly lower-middle-class Bogotanos: policemen, journalists, employees of the Bavaria brewery or the Icasa appliance factory.

That might not have mattered much to the United States. The city had outsized resonance in the Colombian imagination: a U.S. Information Agency survey from 1962 found that 80 percent of Colombians said that they were aware of the Alliance, surpassing other recipient countries; when asked to name a specific element of it, more than half of the Colombian respondents cited housing. That same year, Colombian voters returned the incumbent National Front to office.

“Techo had already fulfilled its propagandistic role,” says Zambrano. It helped establish in Colombia a myth of “the good Gringo, the generous Gringo; the good neighbor.” In tribute, the district was renamed after President Kennedy; today, Ciudad Kennedy is the most populous of Bogotá’s 20 districts.

In the following decades, urban sprawl enveloped Techo, encouraging a broader array of commercial and cultural offerings. Gentrification was set in motion, and many of the children of the first generation of Techo residents were scattered to the periphery. “The social fabric was lost; the sense of neighborhood disappeared,” Zambrano says of the district in the 1990s. “You don’t know who lives by your side; you have all the services, so you don’t require the community.” Seen another way, once it was integrated into the city, it became an attractive working-class neighborhood.

* * *

The Alliance for Progress, already embattled during Kennedy’s brief administration, fizzled soon after. As the decade wore on, the United States would come to see the region’s militaries as a more dependable bulwark against communist subversion than reform-minded democrats of Lleras’s ilk, and commercial ties once again took precedence over development. As Kennedy-era idealism was overtaken by disillusionment, the provision of a base level of social welfare came to be seen not as an imperative of foreign policy, but rather, a discretionary gesture of goodwill.

The Alliance decade closed with dashed hopes. In the realm of housing, for example, the Inter-American Development Bank estimated a deficit of 14 million dwellings by the end of the decade. Three hundred thousand new units would be needed every year just to keep pace with population growth. But, Levinson and de Onís reported, external financing helped construct just 100,000 units a year — and, as in Techo, most did not serve the poorest families, for whom financing was out of reach.

Despite the promise that policymakers invested in Colombia, there too the Alliance disappointed. By the end of the Alliance decade, only 1 percent of the land that had been slated for redistribution under the agrarian reform had, in fact, been expropriated, according to the historian Marco Palacios. The conservative Guillermo León Valencia, whom Kennedy had been eager to see succeed Lleras to keep up the National Front, had little interest in reform, giving its adversaries the opportunity to mobilize, Palacios writes.

Self-construction may be having a renaissance of sorts. The 2016 Pritzker Architecture Prize was awarded to the Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, who, faced with the same public financing constraints as those felt by the ICT, conceived of “half-homes.” Each of Aravena’s rowhouses consists of a frame and core living area, with empty space left between the units so residents can expand them over time according to their own designs and resources.

The United Nations estimates that the world’s urban population will grow by 2.5 billion by 2050, and Aravena has posited his housing design as an economical solution to today’s mass migration to cities. But these formal, ad hoc responses to overcrowding seem hardly more up to the task than Ciudad Techo was a half-century earlier.

* * *

Zachary Laub, an online writer and editor at the Council on Foreign Relations, is based in New York.

Cover photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons