Spring 2016

Souvenirs and Memory: The Meaning of Lost Family Photos

– Rachel Mabe

Slicing out a moment and freezing it — but how many moments can we keep?

The boy is not exactly smiling, but he does look proud. His eyes squint against the summer light. He’s close to the lens, looking right into it, but he’s out of focus. His blond hair is brushed across his forehead, almost into his eyes. His small hands clutch a sheet of white and blue stickers, which he holds by his face, a display for the camera. He stands on a deck, and the trees beyond its rail echo the red-brown color of his shirt. Behind him, in the left corner, an old woman, maybe his grandmother, sits at a picnic table, her head cut off above the eyes. She holds a yellow plastic cup near her lips as though she’s about to take a drink. I imagine this is the boy’s birthday party.

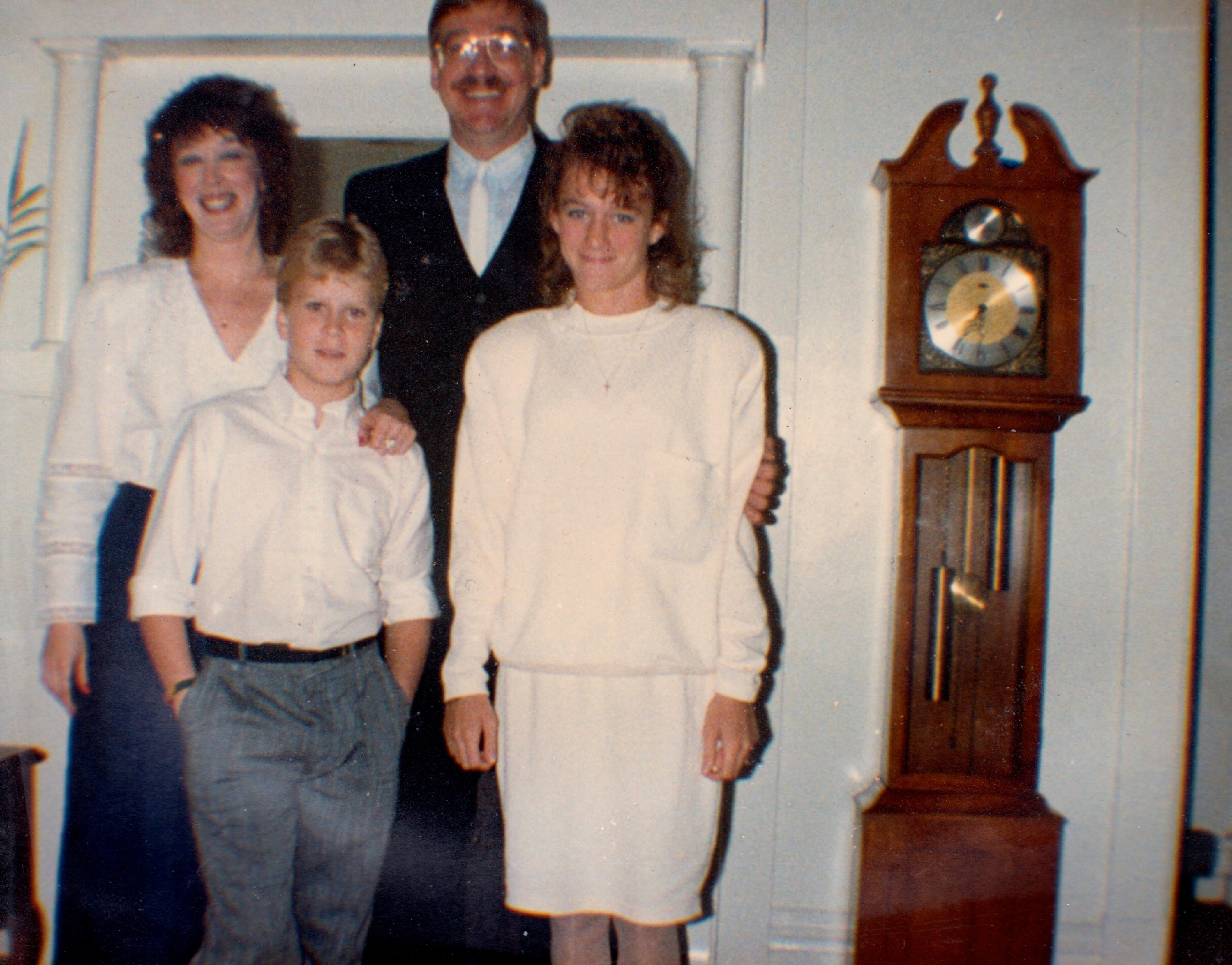

There he is again, now in a collared white shirt and gray pants. His hair is shorter and he’s older, maybe 9, 10, 11. He stands next to a girl a little older than him, perhaps his sister. Perhaps that’s their mother behind him, her hand on his shoulder. Behind his sister, their father, resting his hand on her arm. They pose in front of the mantel, next to a grandfather clock. The boy doesn’t smile, but everyone looks happy. There are five other photographs from the same evening in different combinations: father and mother, father and son (twice), mother and daughter, and the whole group once more.

Walking home from grad school one day last winter, I found these photographs in an alley. I spotted the boy’s blond hair first next to an overturned garbage can, twigs and pebbles arranged on top almost artfully. I crouched down next to him for a long time, looking at his face and wondering how he got there, all alone. Then I realized he wasn’t alone. Nearby, another photo was hidden halfway underneath an empty hummus container, and more were mingled with a dirt-smeared Christmas card. Inside the garbage can sat a small stack of photos, mixed with discarded plastic containers and food scraps. I picked the photos out of the trash, shaking them a bit before stacking them loosely in my hands for the two-and-a-half blocks left before I reached home.

During my senior year of college, I’d lived in West Philly and took the train out to the suburbs for classes. Walking to the station, I’d see interesting things on the ground — rusty bottle caps, children’s drawings — and I’d stop and stare at them for a minute. I’d think about them all day. Then one morning, I came upon an elementary class photo that looked like it had been slashed repeatedly with a razor. And rather than just looking at it and moving on, I picked it up. Since then, there’s been no stopping me. I pick up rusty metal, pieces of broken glass, drawings, notes, rocks, fabric, plastic toys. But I get particularly excited about photographs, because they’re pretty rare. Occasionally I find a stray, but here was a whole collection. I needed to rescue them. I needed to give them a new home.

There’s something about these things — those that were once useful (bottle caps) or important to someone (drawings) — being discarded that makes me sad and also a little excited. I take these abandoned objects and combine them with oil paint to make mixed-media artwork, but I also think that each object is beautiful in its own right, in the natural state of decay I found it in. I have some of these objects displayed throughout my apartment.

At home, I wiped off the photographs with a damp paper towel, and set them to dry on a kitchen counter that I did not often use. I left them there for months. I wasn’t sure what to do with them, but I didn’t want to just stick them in a drawer to be forgotten again. I liked to look at them and think about the people they contained. Who were they? Where were they? Who just threw them away?

I rang the first doorbell and waited. It turned out that the garbage can belonged to a house that had been split up into four apartments. As I counted to 60 in my head, I examined the green wallpaper with pink and white flowers in the vestibule. I rang the bell again. No one came to the door. I rang the second doorbell. I waited; I counted; I rang it again. I rang the third doorbell. An old man with a cane came to the door, looking skeptical. I told him about the photographs I found. I showed him one. They weren’t his, he said. He didn’t know anything about them. I wanted to say, “I need these people to matter. I need them to feel important.” But I couldn’t find the words, so I just said, “Okay, sorry to bother you.” I rang the fourth doorbell. Waited, counted, rang it again, and left. I’ll come back a different day, I thought.

I rang those doorbells because I wanted to find that boy, presumably now a man, and hear his story. But after I went there, I realized I already had a version of him in these pictures, and maybe that was enough; these photographs — any photographs, really — are a glimpse into another life, like walking past people’s houses at night and looking in their illuminated windows. I thought about the story these photographs told. Were these taken in the now-subdivided house? They felt more suburban to me — perhaps taken in the outskirts of Pittsburgh — the grandfather clock next to the bare white walls, the deck out back. The boy’s refusal to smile didn’t seem ominous to me, but it did say something about his personality and place in this family full of grinning people — a mother with big permed hair, a father with large goofy ’80s glasses.

...these photographs — any photographs, really — are a glimpse into another life, like walking past people’s houses at night and looking in their illuminated windows.

These photographs brought to mind the myth of mechanical objectivity — that photographs feel truer than they are, that we see only a version of reality, of the truth. But we do see a version of it, and in some ways, aren’t casual family photographs more real than photographs taken by professionals who strategically choose what to exclude? Photographs might not steal a piece of a person’s soul, but they do capture something — a person at a particular moment in time, or at least one version of them. In college, around the time I picked that class picture off the ground, I thought about photographs constantly because I was writing about them for my thesis. I read Susan Sontag’s On Photography: “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability,” she wrote. “Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

When I look at the boy in the photo, I think of the photographs of my childhood. I wonder how many of my childhood memories are real, and how many are just memories of memories — constructed by looking at photos of my youth, pairing them with stories my parents told me, and tying them together into a story that neatly fits with everything that came after. In those photos, I can also look at myself as a sort of stranger: the person in that photograph knows me — she’s inside me — but I’ll never fully know that person. I can only remember without really being able to feel it — all those hopes and fears, the loneliness and magic of childhood. But at least I have the photographic evidence of those early versions of me. The pictures of the boy have been discarded. So, in a way, the precise versions of him in the photos are lost to him, separated forever from his grown-up self.

.jpeg)

She stands in a parking lot in a white sweater and jeans. A black purse hangs from her shoulder. She holds a video camera in her hand. She wears big round glasses. A mountain looms in the background, behind the cars.

I sit next to my mother at her house in northern Georgia. Our little dogs, hers a shih tzu and mine a gray mix of toy poodle and bichon, lie curled up on the other end of the L-shaped couch. An electric fireplace burns in front of us. The smell of bacon and Swedish pancakes (thinner and slightly sweeter than crepes) lingers in the air. I put this photograph of my grandmother in my pile and pause to look out the window at the mountains before taking another handful out of the big box in front of us. All day, we’ve been sorting through my grandmother’s and great-grandmother’s photographs, and it’s exhausting. My grandmother has dementia — sometimes thinking she’s on a cruise, sometimes thinking my mom has divorced her husband and found a boyfriend, sometimes thinking that my grandfather has left her because he hasn’t come to see her. He died in 2002.

We put everything in piles. There’s a pile for my mom, one for each of my sisters, one for my father, one for my aunt, one for my cousin, one for each of my mom’s cousins. And there’s also a garbage can between us. We fill up the garbage — twice. Some of the photos we throw away are of people we don’t know. Some of them show people making stupid, embarrassing faces. Some of them are doubles. But we also throw away photographs we only have one copy of — photos of people we know and love, who are smiling and looking their best.

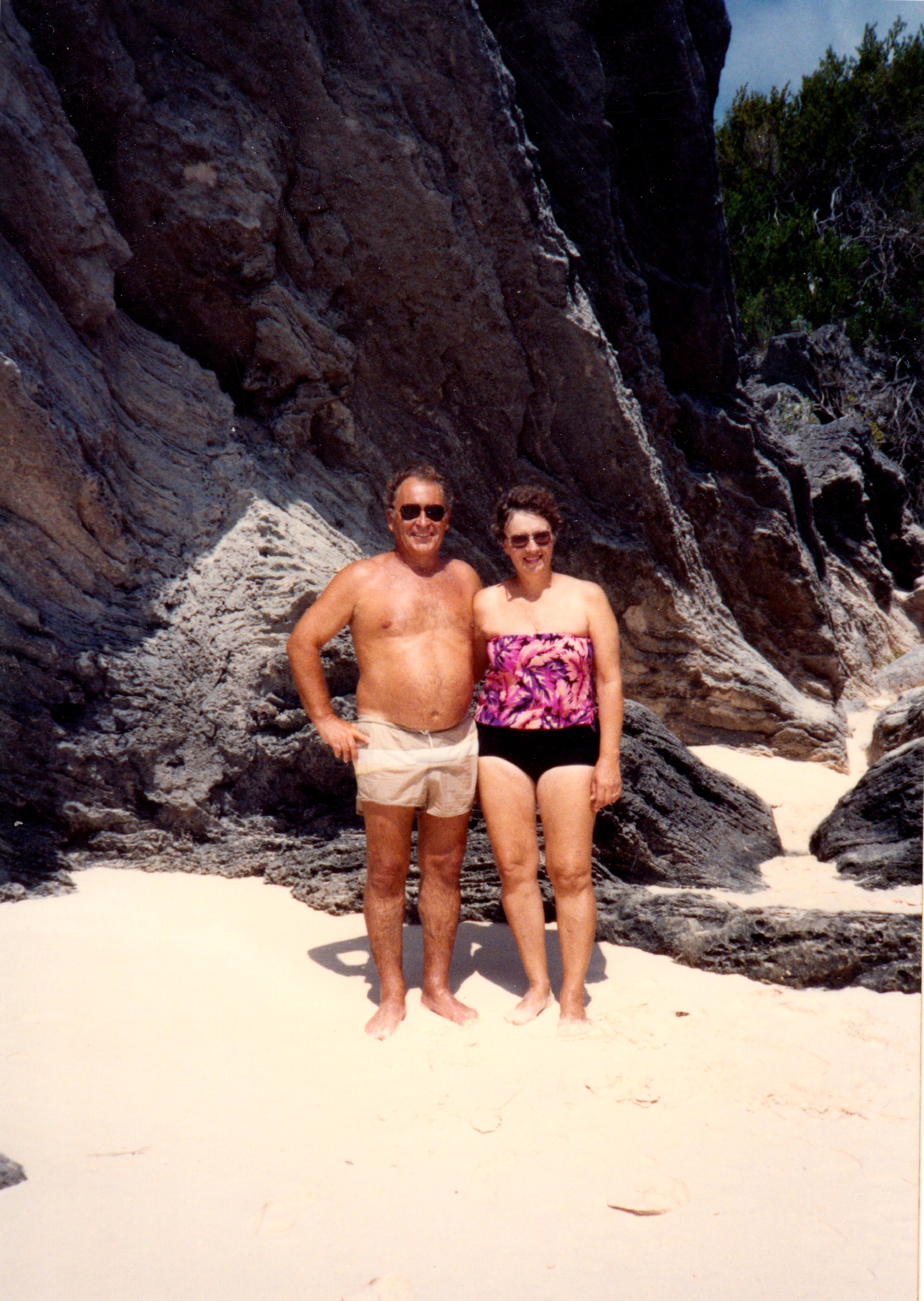

My mom starts the throwing-away. She holds up a stack of pictures of my grandparents on vacation. Once they retired, they hit the road in their dream 34-foot fancy Class A Newmar motorhome — one that felt more like a house than a camper. There’s one of my grandmother on a stone ledge, mountains behind her. There’s one of the happy couple in sunglasses, their arms draped around each other. There’s one of my grandfather in front of a lake, wearing a shirt that says, “Life’s too short not to be FINNISH.” One of them at a picnic table. One of them in lawn chairs. One of my grandfather in the car, his hand on the steering wheel. There’s one of him sitting on a statue of a bear, the bear looking at him lovingly. There’s one of him on the National Mall, and one of her in a canoe. One of her inside an old church, one of him outside it. There’s one of her in a cave, one of him with trees behind him full of fall colors. There’s one of him on a moped, and one where he’s wearing a goofy straw hat. There’s one of her in a bathing suit, her hair pushed back by the wind, the ocean behind her. One of them in the sand. And one of them in the water. And another one and another one and another one.

The vacation photos tell the story of a happy marriage. Of two people who shared companionship and an adventurous spirit. As I grew up, my grandparents lived five blocks from us, so I saw them a lot, and in some ways, I knew them pretty well. On large family vacations, my grandfather and I woke up with the sun. He’d drink coffee and we’d sit side by side in camping chairs staring at a lake or mountains. Occasionally we talked a little, but mostly we kept quiet and admired the scenery. There was much I knew about him, of course, and also much that I knew not to ask about. I knew that he didn’t drink because he was a sober alcoholic. I knew that he stopped drinking with the help of AA. I knew that he’d found a Higher Power, but that he didn’t go to meetings anymore.

He died on my 17th birthday. I knew him as a grandfather, but I never really got to know him as a person. After I got sober myself in my early 20s, I learned that later in his life, he went back to drinking — not all the time, and never at home, but when he was on business trips, he’d drink. A lot. I try to fit that image of him with the man who’d serenely watch the sun come up with me. But I can’t. And my uncles, who worked with him and saw him drink, won’t talk to me about it.

And I’ve had my grandmother all these years. Technically, I still have her. But did I work hard enough to get to know her, the real her? Now when we talk she’s either funny, because her version of the world doesn’t match up with mine — she asks me how I eat fish if I don’t catch it myself and when I tell her I buy it at the grocery store she doesn’t hear me, just says, “Oh, your mom must go fishing for you” — or sad because she wonders why her husband has abandoned her or run off with another woman.

So at first each photograph feels special, a world unto itself. I linger on each one, looking for clues to create a fuller sense of each of them and their relationship, to honor their lives. I take the stack from my mom, but she keeps finding more, and I let her begin throwing them away. And then slowly, I start throwing some away, too. My pile is the biggest, but I don’t have enough room in my life to keep them all. I’m a keeper of stuff anyway, and I’ve already collected photographs from my father’s mother and ones I’ve taken myself. I’m moving to a smaller apartment in a couple of months, and I won’t have room to house everything. And so we toss photograph upon photograph upon photograph into the garbage, because how many photos do you really need of your smiling grandparents in front of a mountain, their arms around each other?

They start to all run together. Who my grandmother was in those big glasses in that parking lot doesn’t seem so different from her in the bathing suit, standing in the ocean. When I look at the boy, losing this particular version of him seems like a tragedy. Maybe the significance of each version of someone is easier to see in strangers because my sense of them isn’t fluid, and I don’t work to fit the photographs into my real life understanding of them.

I never went back to that house to try to talk to the people who lived there. I often walked by it, down the alley and through their parking lot to get to my street. But I never rang the doorbells again. And now, the house is rubble. A fence went up around it and the empty automotive shop next door. Within days, the store was razed. Before they could tear down the house, my boyfriend and I snuck inside after dinner, sliding through a break in the fence. Around back, the door stood open. They seemed not to care about security. As we entered, I raised my voice and said, “Hello? We come in peace,” like I always do when exploring an abandoned building. (I have no desire to startle graffiti artists, vandals, or people looking for shelter or a place to drink or use.) Outside, we’d had the fading spring light, but inside, it was mostly dark — only enough light to create shadows. My boyfriend turned on his phone’s flashlight, and we walked from room to room. We talked about how the house had been partitioned into apartments, and attempted to limn out where one ended and another began. I tried to imagine what the house had been like when it was whole. We talked about what we thought they’d put in its place: apartment buildings, probably — this was a rapidly changing neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

In the basement, we saw a green metal shelf hanging uselessly next to an operable toilet. I decided that I needed the shelf. Everything in this place would all be in the dump in a few days, anyway. My boyfriend pried the shelf loose from the wall. Later, I scrubbed it in my bathtub. Now, it hangs above the toilet in my new apartment, found objects displayed on its three rusting shelves.

Back upstairs, my boyfriend turned off his flashlight, and we got quiet. I stood in front of a sealed fireplace and thought about the boy and his family. Did they ever live here? Where were they now? What were their lives like? Even though I felt like I knew the boy in some ways, he was also, like the fireplace, sealed off and unreachable. I thought about my grandparents. I thought about my childhood self and my current self, and the fact that one day I wouldn’t exist anymore; there’d just be versions of me, frozen in photographs that someone would sift through — a keep pile to their left, a garbage can to their right.

* * * *

Rachel Mabe is currently a second year student in the University of Pittsburgh’s MFA program, where she also teaches. She is an editorial assistant at Vela Magazine and her work has appeared in VICE, Belt Magazine, and The Pittsburgh Anthology. Follow her @rachel_mabe.

All photos courtesy of Rachel Mabe