Spring 2011

A Revisionist's History

– David Garrow

By the final year of his life, Malcolm X had come to represent "a definitive yardstick by which all other Americans who aspire to a mantle of leadership should be measured."

In 1965, a fascinating political voice was silenced when a team of assassins gunned down Malcolm X, a man whose intellectual and religious journey had finally transformed him into an eloquent spokesman for human equality. No comprehensive and credible biography of this signally important black freedom advocate has appeared in more than 35 years, but now, in the appropriately titled Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, Columbia University professor Manning Marable fills this void with a landmark book that reflects not only thorough research and accessible prose but, most impressively, unvarnished assessments and consistently acute interpretive judgments.

Malcolm, of course, chronicled—or authorized journalist Alex Haley to chronicle—his own life in his famous The Autobiography of Malcolm X, published nine months after he died, but Marable definitively establishes that the Autobiography omitted some significant aspects of Malcolm’s youthful criminal life while dramatically exaggerating others. Several chapters Malcolm had prepared were deleted before publication, and he did not review important portions of what millions of readers would think of as “his political testament.” The Autobiography as published, Marable warns, “is more Haley’s than its author’s.”

Born in 1925, Malcolm Little spent his early years in Lansing, Michigan. His childhood was replete with family tragedies: His physically abusive father died violently when Malcolm was six, his mother was confined to a mental hospital when he was 14, and the older half-sister who took custody of him was arrested repeatedly for various minor crimes after Malcolm went to live with her in Boston. Malcolm quit school in ninth grade, and by age 19 his preference for theft and robbery over regular employment had earned him his first of several arrests. Marable corroborates the evidence first presented in Bruce Perry’s valuable but flawed 1991 biography, Malcolm: The Life of a Man Who Changed Black America, that Malcolm developed a close relationship with William Paul Lennon, a wealthy gay white man in his late fifties, who paid Malcolm for sex.

Malcolm also had an older white girlfriend and partner in crime, whom he physically abused. When Malcolm’s sloppiness allowed the police to unravel their small burglary gang, his girlfriend testified against him and served seven months, while Malcolm was sentenced to eight to 10 years. Thus began an odyssey during which Malcolm would reinvent himself several times over. He spent six and a half years, from ages 20 to 27, incarcerated in Massachusetts prisons before being paroled. Lennon visited him, but the man who most changed his life was fellow convict John Elton Bembry, 20 years Malcolm’s senior, who challenged him to develop his intellect by using the prison library and enrolling in correspondence courses. By 1948, when one of Malcolm’s brothers told him that he and other family members had converted to the Nation of Islam (NOI) and wanted Malcolm to convert too, the young prisoner had acquired a profound intellectual earnestness.

The NOI had been founded in 1930 by a mysterious mixed-race man who disappeared in 1934 and was succeeded by Elijah Muhammad, née Poole, a Georgia native who headquartered the small sect in Chicago. The Nation of Islam was Islamic in name only, for Muhammad’s teachings represented an oddball amalgam of black nationalism and science-fiction cosmology that bore only the slightest relation to the Muslim faith. By the late 1940s the NOI had fewer than a thousand members, but for the newly serious young prisoner the group “became the starting point for a spiritual journey that would consume Malcolm’s life.” The NOI taught that blacks’ true ancestral surnames had been lost during slavery, and Malcolm, like most members, adopted X as his new last name.

Malcolm mastered Muhammad’s doctrine, and by mid-1953, less than a year after his release from prison, he was a full-time NOI minister. He was not yet 30 years old. Malcolm’s rhetorical prowess soon emerged as one of the sect’s greatest assets, and by 1955 membership had grown to some 6,000, in large part thanks to Malcolm’s efforts. Over the next six years the ranks of the NOI reached upward of 50,000 as frustrated African Americans responded to Malcolm’s angry but articulate condemnations of white racism and black passivity. Malcolm both denounced all whites (“We have a common oppressor, a common exploiter. . . . He’s an enemy to all of us”) and derided mainstream civil rights leaders as “nothing but modern Uncle Toms” who “keep you and me in check, keep us under control, keep us passive and peaceful and nonviolent.”

Muhammad had assigned Malcolm to the NOI’s Harlem temple. On the afternoon of April 26, 1957, several New York City police officers savagely beat an NOI member who had verbally objected to their treatment of a suspect. Initially the police refused to transfer the severely injured complainant to a hospital, but when they finally did, Malcolm led a well-disciplined protest of about 100 NOI members through central Harlem that eventually swelled to thousands. The Harlem demonstration thrust both the NOI and Malcolm into the public eye more than ever before, and advertised the dominance of the NOI’s militant all-male internal enforcement arm, the Fruit of Islam.

The year 1957 marked a period of “tremendous growth for Malcolm,” Marable writes. As the black freedom struggle in America gained momentum, Malcolm’s interest turned toward arguments over the civil rights movement’s agenda. He “no longer saw himself exclusively as an NOI minister,” and that put him in increasing tension with the sect’s leadership. The NOI’s black nationalism was essentially apolitical, and Elijah Muhammad could “maintain his personal authority only by forcing his followers away from the outside world.”

In January 1958, soon after rejection by a longtime girlfriend, Malcolm married Betty Sanders, a nurse and NOI member with whom he had shared a handful of awkward dates. The partnership was deeply troubled from the outset. Betty combatively opposed the “patriarchal behavior” of her husband and the NOI, and Malcolm “rarely, if ever, displayed affection toward her.” Within a year, Malcolm was writing to Elijah to confess that she was complaining “that we were incompatible sexually because I had never given her any real satisfaction” and that she was threatening to seek it elsewhere. When, nonetheless, Betty gave birth to several children, Malcolm absented himself and treated his wife “largely as a nuisance.”

Growing tensions between Malcolm and the NOI’s ruling circle eclipsed those at home. “The national leadership increasingly viewed the rank and file as a cash register,” Marable writes, and Elijah had developed a habit of impregnating the young women who worked in his office—including Malcolm’s former girlfriend—in flagrant violation of the NOI’s rules mandating sexual fidelity. Talk of the affairs spread, but when Malcolm raised the subject with his closest fellow minister, Boston’s Louis X—later Farrakhan—Louis quickly relayed word to Elijah, who was already jealous of his protégé.

Nine days after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November 1963, Malcolm sarcastically characterized the murder as a case of “the chickens coming home to roost.” But it was his follow-up remark—“Chickens coming home to roost never did make me sad; they've always made me glad”—that created controversy and gave Elijah and his top aides a pretext for suspending Malcolm from his ministerial role. Three months later Elijah made the suspension permanent, and Malcolm announced that he was leaving the Nation.

Malcolm immediately embraced the real Muslim faith, a commitment he cemented with a visit to Mecca in April 1964 that deeply affected his worldview. He returned home with a vastly different political message. “Separation is not the goal of the Afro-American,” he told a Chicago crowd, “nor is integration his goal. They are merely methods toward his real end—respect as a human being.” Malcolm went abroad again in July, traveling primarily in Africa and the Middle East until November. Marable rightly terms this “a journey of self-discovery,” and in most countries Malcolm was feted virtually as a visiting head of state. He told one friendly reporter that he would “never rest until I have undone the harm I did to so many innocent Negroes” during his years trumpeting the NOI’s pseudotheology.

Malcolm’s compass of thought was widening beyond issues of color, and he struggled to find “a new terminology to translate increasingly complex ideas into crowd-friendly language,” Marable writes. As a result, Malcolm could voice contradictory opinions just days apart, praising integrationist leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. one day, then ridiculing King and liberal politicians the next.

But Malcolm’s fatal hurdle remained his violent former comrades in the NOI, who were outraged by Malcolm’s public remarks about Elijah’s profligate behavior. What’s more, “by embracing orthodox Islam,” Marable argues, “Malcolm had marginalized the Nation in one fell swoop,” and his conversion made NOI leaders all the more determined to see him dead. Leading the charge was Malcolm’s former friend, Louis Farrakhan. In December 1964 he declared in the NOI’s newspaper, “The die is set, and Malcolm shall not escape. . . . Such a man as Malcolm is worthy of death.” One night several weeks later, several attackers narrowly failed to grab Malcolm at his own front door, and soon thereafter a trio of firebombs set off at three am sent Malcolm and his family fleeing in their night clothes. He would not escape for long. A week later, three gunmen and two accomplices, all members of the NOI’s Newark mosque, riddled Malcolm with close-range gunfire at a Manhattan lecture hall. He was dead at 39. Several hours later, Louis Farrakhan delivered a guest sermon at the Newark mosque.

Marable’s only significant failing in this otherwise hugely insightful volume is his undisciplined and inconsistent speculation about what, if anything, the FBI—which was conducting extensive electronic surveillance of Elijah Muhammad—or the New York Police Department knew in advance about the assassination team. Until the complete record of the FBI’s surveillance is released, those questions will remain unanswered. What is publicly known is that at least one of the gunmen still lives openly in Newark and has never faced law enforcement interrogation or prosecution.

Much of the official lack of interest in Malcolm’s life, both before and after his murder, stemmed from the fact that “at the time of his death he was widely reviled and dismissed as an irresponsible demagogue.” That caricature has long since been discarded as historians and the wider public have come to realize the remarkable potential that the Malcolm of 1964 and 1965 had as both a fearless champion of black America and an internationally recognized proponent of human equality across all faiths and colors. In fact, Marable is correct when he contends that by the final year of his life Malcolm had come to represent “a definitive yardstick by which all other Americans who aspire to a mantle of leadership should be measured.” This superbly perceptive and resolutely honest book will long endure as a definitive treatment of Malcolm’s life, if not of the actors complicit in his death.

* * *

David J. Garrow, a senior fellow at Homerton College, University of Cambridge, is the author of Bearing the Cross (1986), a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Martin Luther King Jr. Reviewed: "Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention" by Manning Marable, Viking, 2011.

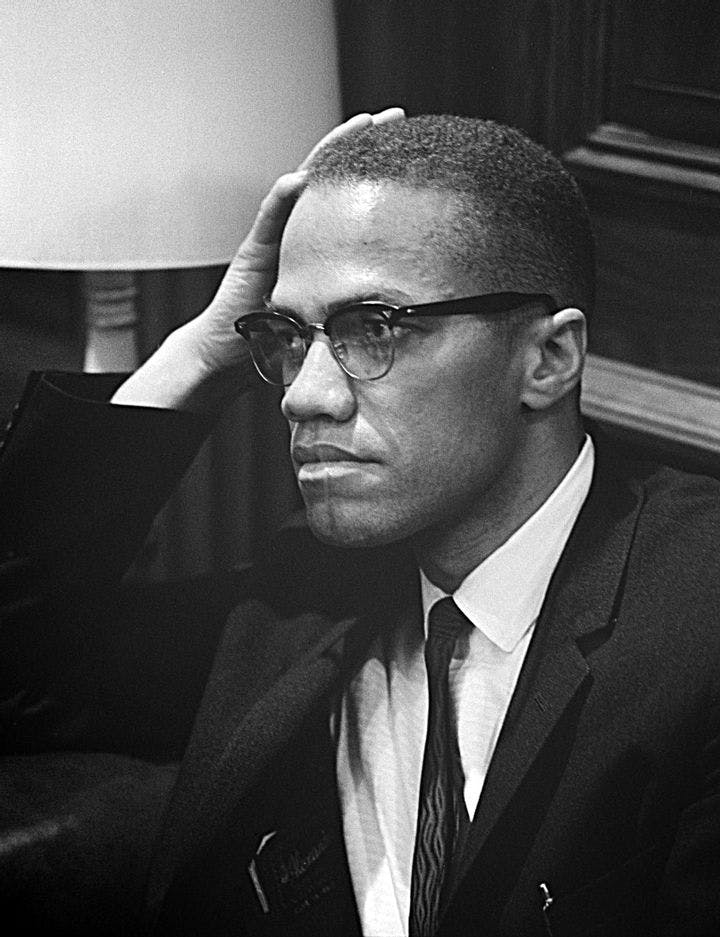

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons