Fall 2020

Relentless Quest

Relatives of Mexican citizens who vanished at the hands of the military in the 1970s still seek answers in a climate of renewed disappearances.

It was a May afternoon in 2019 when I arrived in Atoyac de Álvarez, a small town on Mexico’s Pacific coast in the state of Guerrero. The humidity hit me like a wall as I descended from the car. Ripe mangoes spangled the ground, some blackened and split, and others just fallen and gently bruised, pale orange, slightly larger than my palm.

I had come to join a march and attend a Roman Catholic mass organized by the Association of Relatives of Detained, Disappeared, and Human Rights Victims in Mexico (AFADEM). In the fenced-in front yard of the group’s headquarters, about a dozen older adults fanned themselves in a semi-circle of plastic chairs. The small office had its walls lined with hand-written posters and children’s drawings:

“Abuelito, I love you even though you’re disappeared.”

“Porque los buscamos? Porque los amamos.”

That day’s events commemorated the victims of state terror during a brutal period of civic violence commonly known as Mexico’s Dirty War. AFADEM’s members have spent decades seeking the truth about what happened to those victims, and the marchers that day represent only a fraction of the families of those disappeared during the 1970s and 1980s in Atoyac and its surrounding region.

Many of those involved with AFADEM contest the designation of the period as a “war.” The state purported at the time to have targeted only guerrilla groups who threatened the government. But in reality, it practiced a broad strategy of violent repression against a wide range of citizens, including peasants and schoolteachers. These advocates prefer to say that their relatives were forcibly disappeared as a result of state terror.

AFADEM first began to form in 1972, after the so-called Dirty War led the military and police to detain, torture, and forcibly disappear Atoyac’s residents. And now, nearly fifty years later, the group’s offices are situated on the former site of the city’s military barracks. The Mexican military brought people to be tortured and killed here, where now the victims’ children and grandchildren sit fanning themselves under trees. Their families still don’t know where those victims are – or what happened to them.

Despite the fifty years elapsed since the terror unleashed in Atoyac, the stakes remain high for present-day Mexico. The terror wreaked by military and police forces in the 1970s and 1980s has taken on a more generalized form in the last decade and a half.

The Dirty War period was the first time that forced disappearance was widely practiced in the country. It left approximately 1,200 victims. Today, however, the war on drugs declared by Mexican authorities in 2006 has taken a much higher toll. When President Felipe Calderón declared the war in 2006, Mexico’s army became once again involved in issues of civil security. Forced disappearances spiked. The last fourteen years have left 73,000 victims. And the state of Guerrero, where AFADEM’s members gathered on that day, is one of many that has been overtaken by this fresh wave of violence.

The Weight of History

One of the leaders of that afternoon’s procession was Tita Radilla, a thin woman in her early 70s who is the vice-president of AFADEM.

Radilla continues to search for her father, Rosendo Radilla Pacheco, who was arrested by the army in Atoyac in August 1974 and subsequently disappeared. She has taken her father’s case all the way to the Interamerican Human Rights Court (CIDH), which ruled against the Mexican state in 2009. Even after the government complied with CIDH-mandated searches for Pacheco’s remains, Radilla has yet to learn what actually happened to her father— or even where his body now lies.

The Mexican government has offered public apologies for the events of the Dirty War, but no one has been sentenced for the crimes committed by the state. Radilla sees the clear continuity between the violence that took her father and today’s crisis of violence and forced disappearance in Mexico.

“The impunity that our cases remained in,” she says, “allowed for this to happen.”

As marchers milled around the offices of AFADEM, someone offered sweets made of piloncillo and sesame seeds. Another marcher called for everyone to take bananas from a cardboard box inside to eat along the way.

The Mexican government has offered public apologies for the events of the Dirty War, but no one has been sentenced for the crimes committed by the state.

As we assembled into a caravan to drive to a church in Santiago de la Unión, a few towns over, I climbed with some others into the back of a red pickup truck. I leaned into the wind as we drove into the mountains surrounding the town. Climbing through the sierra, we passed starfruit trees, papaya, cashew, coffee – the abundance of the region whose land and peasants have long been exploited.

In front of me, every so often, the woman in the passenger seat tossed the petals of the white chrysanthemums in her lap out her window. The wind scattered them through the truck bed and onto the road.

This was the same route that the military used to march its detainees in the 1970s and 1980s. It was also in these mountains that guerrilla groups led by two radical schoolteachers – Lucio Cabañas Barrientos and Genaro Vázquez Rojas – found refuge.

Inspired by the Cuban revolution, leftist guerilla groups sprang up in Mexico in the 1960s, including the Popular Guerrilla Group in Chihuahua and the September 23 Communist League in Jalisco. In Atoyac, Cabañas and Vázquez led two revolutionary socialist groups: the Asociación Cívica Nacional Revolucionaria (ACNR) and the Partido de los Pobres.

“The cause was poverty, the cause was misery,” recalls Radilla. “That’s why the people rose up in arms, because they were trying to defend the rights of the people.” The rich land of the Costa Grande region yields crops of coffee, fruit, corn, coconut and sugarcane. But it had long been monopolized by a group of caciques, or local elites. The guerrilleros of that moment mobilized both for self-determination and against the state repression of workers, students and peasants.

After state security forces killed hundreds of student protestors in a massacre in Mexico City’s Tlatelolco Square in 1968, membership in the guerrillas bloomed. “Before, it was more political, people who decided to join because of economic conditions,” says Julio Mata Montiel, AFADEM’s executive secretary. He joined the organization in the 1990s, after being targeted for his own social organizing. “After the massacre,” he explains, “it was the anger, the radicalization, the students.”

Inspired by the Cuban revolution, leftist guerilla groups sprang up in Mexico in the 1960s.

Under President Luis Echeverría, the nation’s military took an aggressive stance against the wave of insurgent groups. Military commander Miguel Nazar Haro, who had trained at the School of the Americas, created the Brigada Blanca (the “White Brigade”), which was comprised of a few hundred police officers, soldiers and intelligence agents.

The White Brigade brought tactics practiced by other School of the Americas-trained military officers in other parts of Latin America to Mexico, removing people from their homes, or detaining them at checkpoints. The army tortured detainees, starved them, and carried out the now-infamous “Flights of Death” known throughout the continent – removing prisoners in helicopters and throwing their bodies into the sea.

Indiscriminate Violence

Despite the political turmoil and violence of the era, members of AFADEM say many of the victims whose memories they preserve had tenuous links to the guerrillas, if any at all.

“The great majority of disappeared people from the decade of the ’70s didn’t have anything to do with armed groups,” says Radilla. “In many cases, they didn’t even know the teachers who were heading up that movement.”

Radilla recalls that Rosendo Radilla Pacheco was disappeared after he participated in a search for other people who had vanished at the hands of the army. The strategy of terror deployed by the government aimed to discourage popular support of the guerrilla groups, some of whose members, like Vázquez and Cabañas, were well-respected community leaders.

Griselda Reyes was a young child, seven or eight, when her father, Bernardo Reyes Felix, became active in the ACNR. She loved to spend time with him; she’d pull out his gray hairs and accompany him to visit friends in the neighborhood.

Bernardo was often absent from the family’s home. Reyes recalls that her grandmother didn’t approve of his involvement in the guerrilla movement. Confronting the repressive Mexican state was no small task for a father of six. Bernardo’s mother scolded him for putting the children at risk. Bernardo insisted, though, that he was doing it because he cared for them.

“The great majority of disappeared people from the decade of the ’70s didn’t have anything to do with armed groups.”

Once he joined the guerrillas, Griselda remembers, her father came and went. He knew he was in the eye of the state. Sometime before Bernardo was disappeared, police arrived at the family home to look for him. “I screamed, 'They’re going to kill us,'” Reyes remembers, “and my mother scolded me.” Bernardo had gone to Acapulco, several hours down the coast, when the family learned of his disappearance. He was detained by judicial police in Acapulco. The family found out from a note, passed from a fellow political prisoner, Octaviano Santiago Dionisio.

“My father always had a lot of things in his head,” Griselda remembers. “He always carried around folded papers in his pocket.” The note was written in pencil on a piece of butcher paper. The family has long lost the message itself, but Griselda remembers the gist of it: “judicial agents got me on September 24, 1972, I’m incommunicado, they didn’t take me to the police station, I haven’t eaten, look for my son.”

A Long Journey To Be Heard

The strategy of state terror continued apace in Atoyac until the early 1980s. “In about 1982, the disappearances went down a bit,” says Radilla.

Yet, the victims’ relatives still had little recourse to justice – or even information. “We couldn’t make an official report, because no one would receive it,” she says. “In that time, many people who reported disappearances were also disappeared. The situation was very serious.”

So the relatives found other ways to make their cases visible. “We always were doing a lot of activity,” says Radilla. “We did marches from Atoyac to Acapulco. We did marches from Acapulco to Chilpancingo, and from there to Mexico City. And we did a lot of hunger strikes. We even took over embassies. But we never got an answer.”

It wasn’t until 1999 that Radilla and other relatives of the victims of state terror were able to officially present their cases before government officials at last. They took their cases first to local authorities in Atoyac, and then to Guerrero state officials in Chilpancingo. Finally, they applied to Mexico’s Attorney General.

In the early 2000s, progress finally seemed possible. President Vicente Fox created a special prosecutor’s office – FEMOSPP, the Special Prosecutor for Past Political and Social Movements – to deal specifically with state crimes committed from the 1960s through the 1980s. Five years later, however, the office was disbanded, along with its promise to bring belated justice.

Fifty years after Atoyac’s first forced disappearances, the Mexican state has acknowledged that, indeed, the so-called “Dirty War” period was a period of intense state repression. Only in 2019 did Mexico finally offer a public apology for the crimes against humanity perpetrated during that period.

Where Are They?

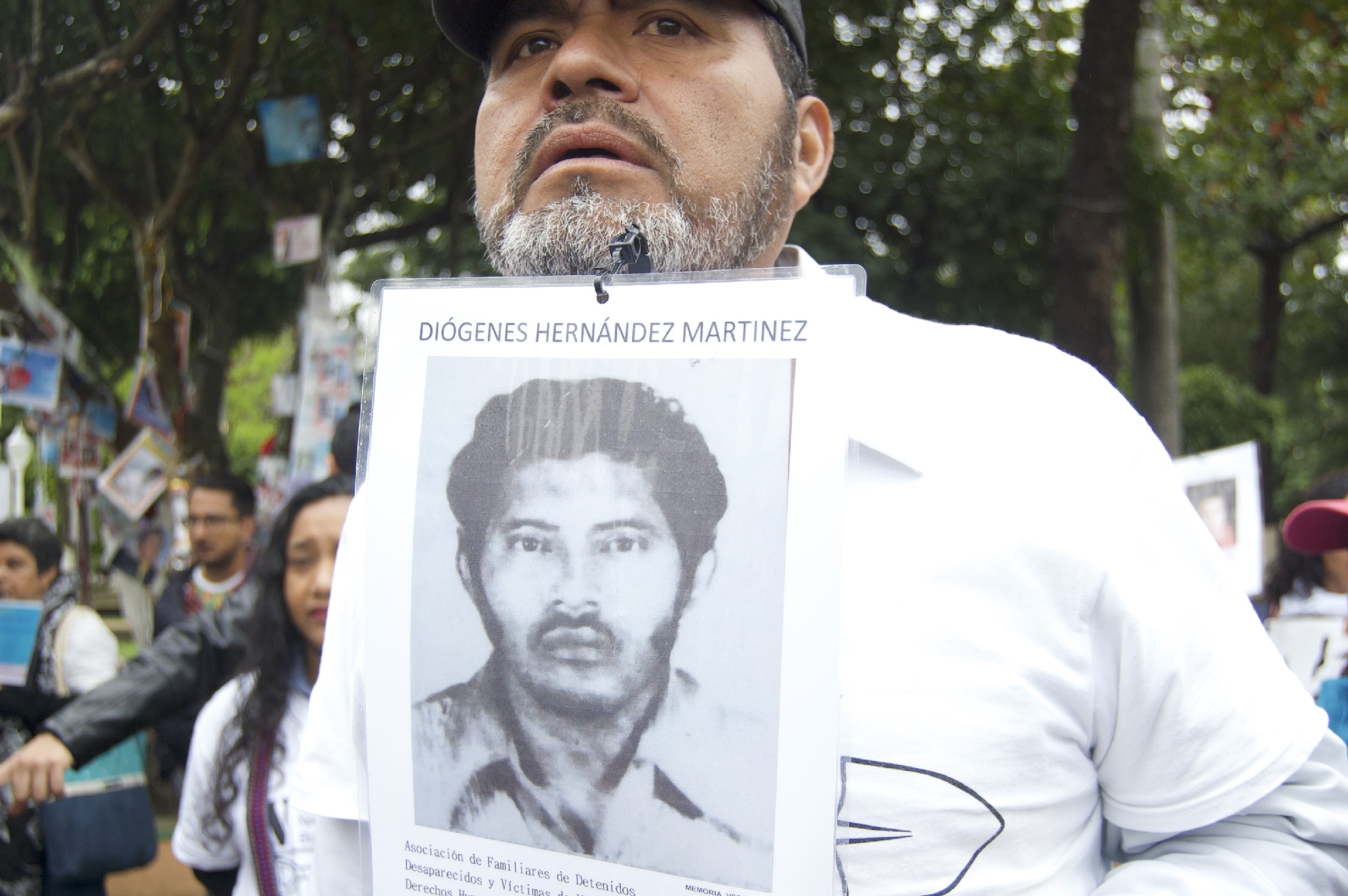

Our drive through the mountains that day culminated at an open-air chapel in the village of Santiago de la Unión. Trees held up the chapel’s tin laminate roof. As we filed in, members of the procession held aloft photos mounted on cardboard. Each image, a blurred black-and-white portrait from the 1960s and 1970s, depicted a victim, and their relatives placed the portraits around the altar.

Little is known still about what happened to these hundreds of victims. In the offices of AFADEM, their children continue to grapple with the legacy of state violence unleashed on their families – and on Mexico as a nation. Many of the likely perpetrators have long passed away. And what might constitute “justice” takes on a different meaning with each family.

Yet one injustice that persists is the military’s continued opacity about the events of the 1970s. Mexico’s military has kept its archives closed. Griselda Reyes believes those files may hold the key to knowing how her father spent his last moments.

“We don’t know if they threw him into the sea, [or] if they left him in a mass grave,” says Reyes. “When they arrested him, they had to have asked him his name. They had to have written it on some piece of paper. It would be a clue.”

While the immediate perpetrators of the violence of Atoyac are gone, they marked a bloody path for those who follow in their steps. Mexico’s first practitioners of forced disappearance passed this tactic on to a new generation of military officers and police.

The 2014 disappearance of the 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Teachers College – the same school attended by Lucio Cabañas – brought the issue of renewed disappearances in Guerrero to national attention.

One injustice that persists is the military’s continued opacity about the events of the 1970s. Mexico’s military has kept its archives closed.

Family members of the victims of present-day disappearances around the country began to organize together to search for their loved ones. And AFADEM has collaborated with other groups in the state of Guerrero to create new organizations, such as the Frente Guerrero por Nuestros Desaparecidos, across Mexico.

Today, Radilla and Reyes march, search and strategize alongside fellow Mexicans who also have suffered the disappearance of a father or brother or uncle in more recent times. They repeat a common refrain in these demonstrations: Dónde están? Any justice must begin with an answer to that question from the Mexican government: Where are their loved ones?

At the chapel that day, some hundred faded faces stared out at us from the era of the so-called “Dirty War.” Others were only represented by handwritten names. The priest read out their names of all the missing, one by one. To each of them, those gathered there replied: Presente.

Madeleine Wattenbarger is a freelance journalist based in Mexico City, where she covers Mexican politics and human rights.