Fall 2020

Reversing a Bloody Legacy

Belgium plundered the Congo for more than seven decades. The pernicious effects of that colonial rule have lingered long after independence was won in 1960.

On June 30, 2020, sixty years after the country known today as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) acquired its independence, Belgian King Philippe I issued a statement in which he expressed his “profound regrets” for the atrocities committed by his ancestor Leopold II and for the “suffering and humiliations” caused by colonial rule in that nation from 1885 to 1960.

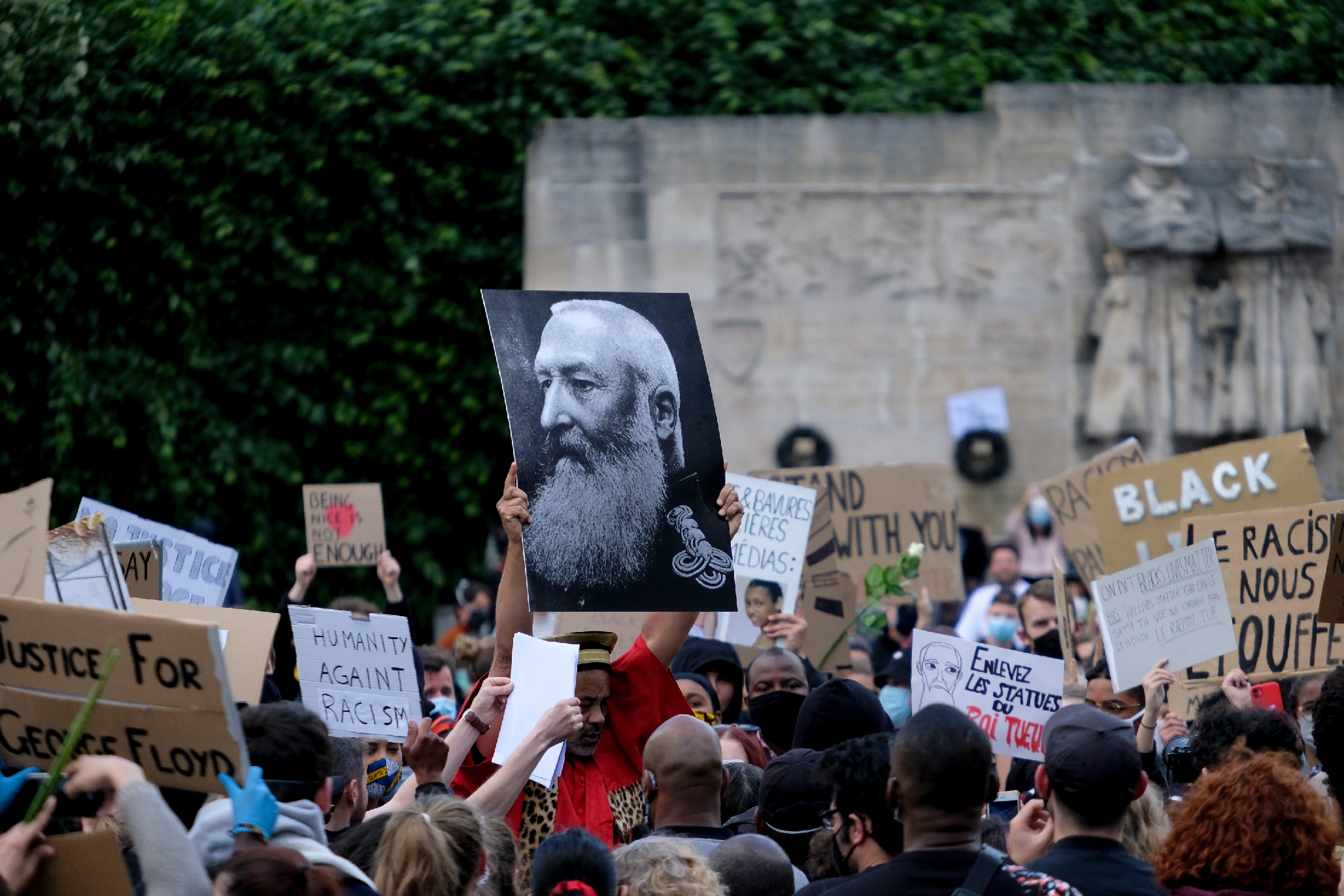

The statement came amidst the global attention given to the racial reckoning occurring in the Unites States in Spring 2020, as well as a wave of defacements of statues of Leopold II across Belgium. And while the King’s statement was a welcome development in Belgo-Congolese relations, it has little to offer in resolving the trauma suffered by the Congolese people as a result of Leopold’s slave labor regime and the looting of the Congo.

It also did nothing to ameliorate the unending crisis created by Belgium’s mishandling of the transfer of power in 1960-61. Independence spurred a series of malign Belgian actions in those two years, including engineering the June 26, 1960 theft of the Congolese state’s investment capital, inciting a mutiny of the armed forces on July 5, 1960, and encouraging the secession of Katanga on July 11, 1960. These activities also provoked the January 17, 1961 assassination of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, the country’s first democratically elected head of government.

King Philippe I's statement did nothing to ameliorate the unending crisis created by Belgium’s mishandling of the transfer of power to the DRC in 1960-61.

King Leopold’s reign of terror was brought back into clearer focus by Adam Hochschild’s 1998 bestseller, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. It was quickly translated and published in French and Flemish (or Dutch), the two major languages of Belgium. And as King Philippe’s statement reverberates, it is important to recall for what exactly he is expressing his “profound regrets.” What can be done now, through a process of redistributive justice and reparations, to repair the harm that Belgium and its allies have done to the Congolese people?

Six decades on from independence, the people of the DRC still grapple with the historical trauma and the debilitating political and economic crisis for which Leopold and his Belgian colonial successors are responsible. They continue to struggle to build – in the words of their national anthem – “a country more beautiful than before.”

King Leopold’s Brutal and Predatory Rule

King Leopold II was born in 1835. He was the son of Leopold I, and a cousin of Queen Victoria of England. He grew up with a great passion for the acquisition of overseas colonies, which he considered as indispensable for a country’s greatness.

As a relatively new state created after the Belgian Revolution of 1830 and the establishment of a constitutional monarchy the following year, Belgium’s political class shunned imperialist quarrels over colonies. But the nation’s king started plotting to acquire one after his accession to the throne in 1865. By 1878, a Comité d’Études du Haut-Congo (the Upper Congo Study Committee), CEHC, was created to promote Leopold’s interests in the Congo basin.

Henry Morton Stanley, the Welsh-American journalist, was hired as the king’s colonial agent in the Congo, where he established administrative posts manned by European agents, and negotiated so-called treaties with African traditional rulers – most of whom could not read or write. The “X” these rulers placed next to their names signed away their lands to the Association Internationale du Congo (AIC), which had succeeded the CEHC in 1879.

Stanley’s impostures were the means by which Leopold’s territorial claims to the Congo basin were approved by the major powers, beginning with the United States in April 1884, when President Chester Arthur signed a treaty recognizing the flag of the AIC as that of a friendly country. (This was probably the first time in history that a presumably research organization was recognized as a sovereign state!)

It is often said that the Berlin Conference, which took place between November 15, 1884 and February 26, 1885, awarded the Congo to Leopold. But distinguished Belgian historian Jean Stengers may be right to argue that this is a myth.

Belgium’s political class shunned imperialist quarrels over colonies, but the nation’s king started plotting to acquire one after his accession to the throne in 1865.

The truth is much stranger. The conference agenda's three main items were freedom of navigation on the Congo and Niger rivers, freedom of trade in the Congo basin, and rules for territorial claims in Africa’s coastal areas. Only on the last day did German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck read a letter from King Leopold stating that all nations participating in the conference (save Turkey) had endorsed his personal territorial claim. A standing ovation by the delegates affirmed it, yet the recognition remained unmentioned as a binding decision in the General Act of Berlin that followed the meeting.

Leopold quickly pushed a resolution allowing him be the sovereign of two independent states simultaneously through his nation’s Parliament. By May 29, 1885, a royal decree proclaimed the existence of the Congo Free State [CFS]. The people of the Congo were not consulted in the proclamation of this alien state, nor in the naming of a new absolute ruler, who would never set foot in their land after his accession on August 1, 1885. The results were catastrophic.

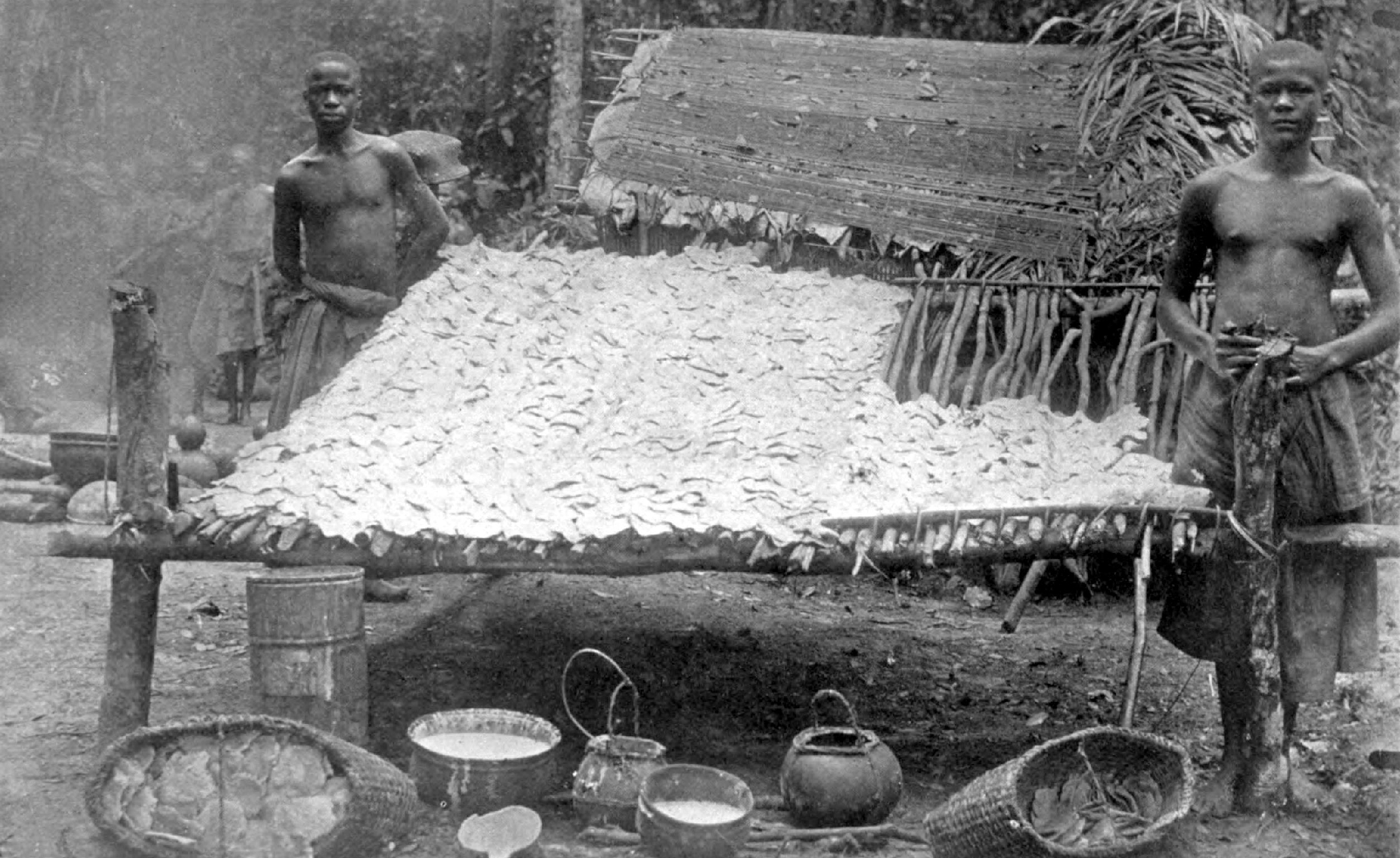

Stengers observes that Leopold owned the Congo in the same way that John Rockefeller owned Standard Oil. He was an absentee landlord who used the labor of his newly enslaved subjects to produce the maximum quantity of resources needed to satisfy his enrichment needs. The European administrators of the CFS were paid bonuses tied to productivity, and used violence and intimidation to work people to death, particularly in the collection of ivory and wild rubber. Failure to meet the required quota of rubber for each village, for instance, resulted in women and children being held hostage until it was met. These women were generally subjected to rape and other forms of violence, while children faced the torture of long hours without food or water.

The king’s agents, the African sentries charged with overseeing rubber collection, and the mercenaries of the Force Publique (FP) – or the state militia - all committed unspeakable and heinous crimes, including extrajudicial execution and arbitrarily cutting off people’s hands, including those of children.

King Leopold’s arbitrary and tyrannical rule enriched himself, his family, and Belgium. But millions of the people of the Congo suffered and died. And even when an international outcry against his brutal colonial system led to its end in 1908, Leopold was compensated handsomely for losing an overseas kingdom that was 83 times the size of Belgium.

Yet Belgium’s monarch remained inconsolable, and he took revenge for having “his Congo” taken away by burning the Congo Free State archives – an operation that took eight days. He did not want posterity to know what he did in the Congo, but alternative sources of information about his rule do remain available to researchers today.

It is an irony of history that Leopold used wealth from the Congo Free State for the construction of public works, urban projects and private properties for himself in Belgium and elsewhere. The man who pillaged the CFS thus earned the laudatory epithet of the “Builder King.” Yet these monuments in his honor in Belgium, which are now proving so controversial, were erected only after the international condemnation of his abuses and atrocities in the Congo had died down.

The Belgian Congo: Leopold’s Legacy Continues

Leopold’s dream of his own colony ended in 1908. But Belgium’s annexation of the Congo that same year meant that it remained firmly in control.

In his book, King Leopold’s Legacy: The Congo Under Belgian Rule, 1908-1960, British historian Roger Anstey argues that while the Belgian government did reduce the level of abuse and atrocities, the previous system of economic exploitation remained more or less intact. The Congo was a major source of capital accumulation for Belgium, and the profits it generated financed its own colonization. The Belgian colonial regime was not as satanically brutal and blindly criminal as its predecessor, but it was just as predatory, authoritarian, and racist.

The Congo’s traditional ruling class, formerly the chief beneficiary of rural surplus labor, was incorporated into the authority structure of the colonial state to facilitate extractive and repressive tasks, including tax collection, labor recruitment, conscription, and public order. Any chance that African merchants – once active in long-distance trade – might have to become a prosperous and autonomous sector of the economy were destroyed by the trading monopolies granted to concession companies, as well as discriminatory policies enacted to protect European and Asian merchants from African competition.

The Congo’s immense resources made it pivotal in both world wars. The Force Publique, serving as the colonial army, played a major role in the defeat of Germany in East Africa, including its brilliant 1916 victory at Tabora in western Tanzania (then the major part of German East Africa) and in the battle of Lake Tanganyika (which was depicted in John Huston’s 1952 classic film The African Queen). These victories also earned Belgium power over Rwanda and Urundi (now Burundi) through the League of Nations mandates.

The FP played a key role in Allied Forces’ victory in World War II as well by defeating Italy in Ethiopia. Congolese soldiers also won the major battles of Asosa, Gambela and Saio (now Dembi Dollo). Yet Robert Godding, the post-World War II Belgian minister of colonies, admitted publicly that £40 million in profits from the Congo paid for all the expenses incurred in that war, and those of the Belgian government in exile in London as well. Belgium’s gold reserve remained intact.

The Congo’s immense resources made it pivotal in both world wars.

Belgium attempted to maintain its political and economic influence as independence loomed and future relations were negotiated. A Political Roundtable in early 1960, attended by virtually all major Congolese politicians, fixed the date of independence for June 30, 1960. While the Congolese saw this as a victory, the Belgians already had begun preparing a neocolonial solution to perpetuate their control over the Congolese economy and influence its new and inexperienced political class.

An Economic Roundtable Conference, held between April 26 and May 16, offered a preview of Belgium’s strategy to deal with a newly independent Congo. And only four days before independence, on June 26, 1960, the Belgian government announced the privatization of state capital, selling state-owned shares on the cheap to large private corporations. In essence, the new state’s investment capital was looted.

The government also asked Belgian corporations and subsidiaries based in the Congo to transfer their headquarters to Belgium, thus depriving the new state of significant taxes and royalties. As it did so, Belgium also left virtually all of its public debt behind. This open robbery of Congolese assets had never been accepted by its people, and the dispute remains unresolved to this day.

Belgium’s aggression against the newly-independent state was not confined to the economy. The Belgian commander-in-chief of the Force Publique engineered a mutiny on July 4, 1960, and invited military intervention by Belgium on July 10. The mineral-rich province of Katanga seceded on July 11. Such chaotic machinations sought to discredit new Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. And, taken together, the Katanga secession, the resulting international crisis, and Lumumba’s removal from office (and subsequent assassination by a Belgian execution squad) helped ensure continued Western control of the Congo.

Indeed, major world powers have clearly opposed allowing the DRC to assume full territorial, political, and economic sovereignty since independence. Sixty years later, the Congo remains a weak, neocolonial state seeking to recover the sovereignty for which Lumumba fought and died as the victim of political murder engineered by Belgium and the United States with the complicity of corrupt Congolese leaders.

Postcolonial Congo: In The Shadow Of King Leopold

While Belgium did not have an official policy of apartheid in the Congo, virtually all aspects of life were covered by the color bar and de facto racial segregation, including seating arrangements in Christian churches. This environment helped pave the way for the emergence of a class of évolués (for “evolved”) or middle-class Africans in the post-World War II era. This class created a lasting legacy by aspiring to gain equality with Europeans in employment, access to public accommodations previously reserved for whites, and to legal and political rights. They were also the group that rose to political power at independence, and internalized a culture of arrogance, disdain, and neglect of ordinary citizens.

Since independence, the DRC has been governed by leaders groomed for political office by Joseph-Désiré Mobutu (Mobutu Sese Seko), a former protégé of Patrice Lumumba who betrayed his mentor for fame and money.

,_Prins_Bernhard_reikt_Presiden,_Bestanddeelnr_926-6031.jpg)

From his September 14, 1960 coup d’état against Lumumba, his collaboration with the CIA and the Belgians to eliminate him, and a 32-year tenure as dictator, Mobutu came to see himself as the king of Zaire (the name he gave to the country in 1971, which disappeared with his rule in 1997). Yet more important still was that Mobutu perceived himself to be a successor to Leopold II as literal “owner” of the Congo and its resources. He offered state property to his friends and cronies, refusing to distinguish between the state treasury and his own bank account. And while most of Mobutu’s collaborators were eliminated from power by his successor Laurent-Désiré Kabila (who won power with support from Rwanda, Uganda and Angola), many of them made a comeback under Laurent’s son, Joseph Kabila.

The Leopoldian legacy is alive and well in the Mobutu-Kabila political fraternity, which now includes quite a number of millionaires and a few billionaires. Currently in a coalition government with President Félix-Antoine Tshisekedi, who was elected in December 2018, this essentially mediocre and corrupt political class constitutes a major obstacle to economic and social change in favor of ordinary people.

Mobutu perceived himself to be a successor to Leopold II as literal “owner” of the Congo and its resources.

King Leopold’s legacy helps explain the persistence of what one might call “the DRC paradox.” The country remains extremely poor in terms of the standard of living of its inhabitants. It still lacks appropriate infrastructure for development, despite its enormous wealth in natural resources, and thousands of highly trained professionals who often find greater success working abroad or in international organizations.

The roots of this paradox reside principally in the legacy of predation, authoritarianism and extreme violence associated with King Leopold’s rule and its continuation in Belgian colonial rule. This legacy was replicated in postcolonial Congo through the crisis of decolonization in 1960-61, U.S. intervention in that crisis to protecting Western access to the Congo’s strategic resources, and the rise of a new African oligarchy more determined to enrich itself than develop the country.

In order to stay in power for the purpose of avoiding prosecution and maintaining impunity, members of this class continue to use violence and electoral fraud to cling to power and protect their ill-acquired wealth. While pretending to work within the Congo’s democratic institutions, they do everything possible to undermine the rule of law in order to remain on top of the political game. The consequences are the persistence of a fragile state, under the control of a Mafia-type political class.

An End to the Leopoldian Legacy?

Removing Leopold II’s statues in Belgium is fine, if that is what the majority of Belgians want. But gestures and statements change nothing in the DRC. The people of the Congo want redistributive justice and reparations, both for the wrongs suffered by their ancestors and the present consequences of Leopold’s legacy in their country. Belgium should help the Congo erase predation, authoritarianism, and violence as instruments of rule and the impoverishment of the people.

Such support should go beyond mere dollars or euros. Genuine political support for democracy is lacking from countries that preach democracy and exert pressure for change in non-democratic nations.

In the DRC, the quest for democracy has been going on for decades. One major event in this saga was the Sovereign National Conference held in 1991-92 in Kinshasa to interrogate the past and chart a new path for the country. Western powers gave financial assistance to the conference, but their moral support for it was lukewarm. Given their strategic and economic interests, they soon tired of unending debates at the People’s Palace, and preferred quick solutions from “moderate” leaders. And yet, this meeting was the most successful national conference of the 1990s in Africa, both in terms of the scope of issues discussed, and the detailed reports on the main issues facing the country and how to address them.

One failed test for Western powers’ respect for democracy in the DRC came on August 4, 1992. The National Conference’s 2,842 delegates voted by standing ovation to change the country’s name from Zaire back to the Congo on that day. But Mobutu’s rejection of that decision caused the international community to remain silent, and no country in the world recognized the right of representatives of the Congolese people to reassert the legitimate name of their country. It was only on May 17, 1997, when Laurent Kabila, by a stroke of the pen, proclaimed himself president of a country now called the Congo, that the international community concurred in the change of the name.

The Sovereign National Conference held in 1991-92 in Kinshasa was the most successful national conference of the 1990s in Africa.

International support by pan-African and progressive forces to support free and fair elections in the Congo is necessary to allow its people to choose their own legitimate and responsible leaders. The presence of enormous mineral and other forms of natural wealth in the DRC is not a scandal. The real scandals of the Congo are that a country so rich in natural resources remains among the poorest nations on earth, and that it has seen the flight of its capital to its rulers and their external business partners.

The scope of reparations due to the Congo might encompass an article of its own. But Belgian and Congolese leaders must discuss the major wrongs and harm done to the country and its people since 1885 – and agree on both the substance and schedule of delivery of reparations for them. The beneficiaries should include not only the Congolese state, but also the descendants of the many people who perished in these tumultuous events.

Recent worldwide protests against police brutality and institutional racism in the wake of the murder of George Floyd by officers of the Minneapolis Police Department on May 25, 2020 have given a new impetus to addressing many global injustices, including Belgium’s responsibility for the heinous crimes committed in the Congo by both King Leopold II and his successors.

Statements by King Philippe and by the Belgian government are not enough. What the Congolese need from Belgium and other developed Western countries is greater support for democracy, and also for redistributive justice and reparations. The nature of the reparations must be negotiated by Belgian and Congolese authorities in the shadow of their shared history.

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja is a professor of African and Global Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His book, The Congo from Leopold to Kabila: A People’s History won the 2004 Best Book Award from the African Politics Conference Group (APCG). He has worked with the United Nations Development Programme in Nigeria, and was the Director of the Oslo Governance Center from 2002 to 2005.

Cover image: A statue of King Leopold II of Belgium in Brussels, Belgium, on June 10, 2020. (Olivier Hoslet / EPA-EFE / Shutterstock)