Summer 2018

While Negotiators Talk NAFTA, Mexicans Grapple with Automation

Automation may be reshaping North American manufacturing and the North American workforce, but it is not a part of NAFTA negotiations. And so, cities like San Luis Potosí go on grappling with the ground-level changes under way.

Small green packets speed along a conveyor belt on their way to a glass box where the robots work. The packets file into a straight line. A robotic arm swings left, picks up three packets via suction, and then precisely places one after the other on another conveyor belt. While the first robotic arm releases packets, a second identical arm picks up three more.

It’s a mechanical ballet, set to the tune of gentle clicking, as each packet – containing oil for hair-dye kits – lands on the conveyor belt. The robots work faster than humans. They don’t complain. They don’t need bathroom or lunch breaks. They are the future.

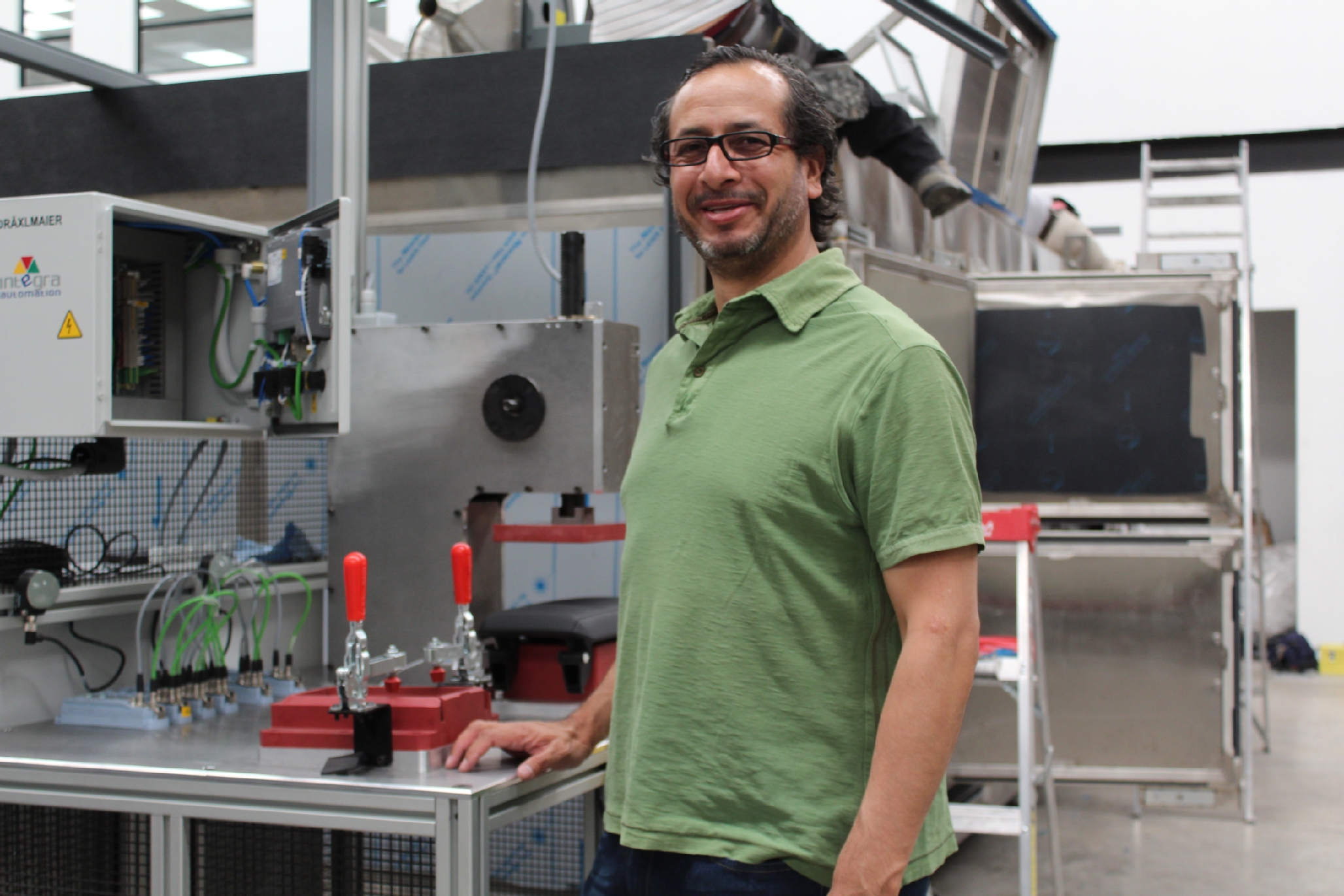

“Automation is an obligation,” says Eric Palencia, CEO of Integra Automation, the Mexican company that designed the line for the little green packets. “Otherwise, we are just a country of cheap labor. We are competing with countries where most processes are automated.”

The line is nearly ready to be deployed at a factory in San Luis Potosí, a colonial city of one million people that has transformed beyond gold and silver mining to become an integral part of Mexico’s manufacturing heartland. Global automotive heavyweights such as General Motors and Cummins have set up production here to take advantage of the low costs and strategic location, halfway between the Mexican capital and the U.S. border. BMW plans to open a $1-billion factory in 2019. (The city took a direct hit in early 2017, when Ford canceled its own planned factory amid tariff threats by U.S. President Donald Trump).

According to the International Federation of Robotics, the automotive industry is by far the biggest customer for robots in Mexico, making San Luis Potosí an automation hub. But across the country, robot density is still far below the world average. While Mexico is embracing robots at a fast clip, it ranks 31st on the global scale – far behind its North American neighbors and even farther behind automation leaders South Korea, Singapore, and Germany.

The robot ranking helps illustrate the World Economic Forum’s classification of Mexico: it is a “legacy” country for production, running the risk of getting squeezed between “leading” countries, such as the U.S., that can offer more advanced manufacturing, and “nascent” countries – much of Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Eurasia – that can offer lower-cost labor.

Today, the Mexican economy appears to be at a crossroads. While President-Elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador envisions a fully revitalized country, the uncertain fate of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the accompanying tariff battle started by President Trump hang overhead. How the Mexican economy develops in the future will depend, at least in part, on the contents of a renegotiated NAFTA. It will also depend on how effectively Mexico – and North America overall – integrates automation and deals with its impacts on the workforce.

“We need to find a way for the three countries to continue to work together to be competitive as a region, and for Mexico to scale up so that it can complement the U.S. and Canada,” says Beatriz Leycegui, a consultant who previously represented Mexico as deputy minister for international trade.

Many economists and labor experts say the primary challenge for the North American economy is to adjust to the new technology, instead of bickering over immigration, offshoring, and imports. A Ball State University study demonstrated that nine out of 10 manufacturing job losses in the U.S. are due to productivity gains.

Nevertheless, there are no outward signs that automation is being discussed by the U.S., Canadian, and Mexican negotiating teams.

“It's hard to put automation and technology on the table per se in trade talks because you don’t know how that's going to change or evolve,” concedes former U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Earl Anthony Wayne, who authored a recent report about the skills gap among North American workers. Moreover, trade policy alone cannot address labor disruptions from technology.

And so, with such critical considerations relegated to the background on the continental level, cities like San Luis Potosí go on grappling with the ground-level changes under way.

Automating Automotive

Automation has been a fixture of the automotive industry since the days of Henry Ford. The invention of the automobile itself put many blacksmiths and horse handlers out of work. But it also created new businesses and services, such as roadside hotels and fast-food joints for the motoring set.

Mexico ranks seventh in global automotive production, having produced four million vehicles in 2017. The U.S. ranks a far second behind top producer China, while Canada ranks eleventh. Overall, North America produces one out of every five vehicles made worldwide. The process, in large part due to NAFTA, is highly integrated, with components crossing borders often more than once. Auto-leader Michigan, for instance, might import aluminum from Canada to manufacture car parts, which are then sent to Mexico for final assembly, before shipment back to the U.S. for sale at dealerships.

Between 1994, when the free trade agreement came into force, and 2016, employment in Mexico’s automotive industry expanded seven-fold to 767,000 jobs. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the U.S. shed about 170,000 automotive jobs during the same period, leaving it with almost 953,000. Low wages explain much of the growth in Mexico. In trade talks, the U.S. has pushed for incentives to produce auto parts in geographies where wages top $16 an hour. On average, Mexican auto-parts workers earn about $2 an hour. The implication is that either Mexicans need to earn more, or the jobs need to stay in the U.S., where auto-parts workers average about $20 an hour.

Mexican Economy Minister Ildefonso Guajardo has emphasized this point repeatedly, calling it “absurd” to fight over jobs that likely will not exist in five years.

Incentives to employ robots are much higher when workers make $20 an hour versus $2, but at the same time, robots are getting cheaper and easier to integrate into production. That means Mexico risks losing many of the automotive jobs it has gained on the back of low-cost labor. A new spot-welding robot with a useful life of 10 years sells for less than $50,000, and deploying that robot in a factory setting might bring the total cost to $130,000. That is cheaper than the combined 10 years of wages for the workers the station will replace, even in Mexico.

The Boston Consulting Group predicts that the U.S. could use robots for as many as 45 percent of manufacturing tasks by 2025, while Mexico is seen possibly relying on robots for 35 percent. The coming shifts have diverse implications for the continent’s manufacturing and labor landscapes.

Mexican Economy Minister Ildefonso Guajardo has emphasized this point repeatedly, calling it “absurd” to fight over jobs that likely will not exist in five years. “NAFTA discussions have to look to the future,” he said this May at a research and development center for tires.

Man Meets Robot

Staffing plans for the new BMW facility in San Luis Potosí are another sign that the future is now. The automaker is to employ 1,500 people and 500 robots. Some of the humans from that group are learning how to disassemble a hulking orange robot at a training center run by KUKA, the German robot manufacturer. They need to know how to clean it, how to repair it, and how to mount it again. They have a week to master the skills.

Safety glasses on, the trainees rig a pulley system to lower an axis from a robotic arm onto a pushcart. Chains clank against each other as the swinging metal carcass inches closer to the ground. In this session of man-meets-robot, the objective is to deploy everyday tools – a wrench, a screwdriver – to disarm the robot and clean it. Maintenance will be key once the robot is in use at the factory. A downed robot means many hours of lost productivity.

Instructor Ricardo Ricárdez says most trainees are excited at the opportunity to tinker with the machines. Work with robots, after all, is better paid than other assembly jobs. Often 30 percent more. But some are intimidated. Each robot is worth more than the typical Mexican factory worker earns in a year, and the machines are powerful enough to lift nearly 800 pounds.

Directing a robot via remote control is a little like driving a car for the first time, Ricárdez explains. With an overzealous push of a button, the operator can send the machine colliding into another object. Most trainees leave KUKA, he says, feeling like the robots are their allies, that they will help them do their jobs – and stay employed: “They see that, increasingly, there are more robots in industry overall, so they recognize that coming here is an opportunity to learn and integrate – because new technologies are coming.”

Nearby, engineer Victor Juárez demonstrates how to move a robotic arm that, if fully extended, would tower several feet above the average Mexican. The robot traces lines autonomously within a boxed-off work station. The movements are coordinated via a handheld console from the outside. An operator with a high-school education can grasp the programming, he assures. The robot could be deployed for a variety of purposes, such as to weld auto parts, stack boxes of breakfast cereal onto pallets, or glue together electronics.

The way Juárez sees it, the robot is another tool. It does what a human tells it to do. One sold today will be obsolete in a few years. “A robot isn’t going to be able replace a human. You still need that human touch,” he says.

“Our goal is to ‘utilize’ our employees and robots according to their strengths,” BMW said in a written response to questions from The Wilson Quarterly. “Hard work can be done by robots. And the creativity of human beings is unbeatable.”

A 2017 McKinsey report asserts that less than 5 percent of current occupations can be fully automated. But more than half of all jobs can be at least partially automated. For many professions, that means change is a given. What is in the air at the KUKA center is the fact that humans will increasingly supervise the work of robots, while low-skill workers run the greatest risk of having their jobs automated. Once displaced, they will be in competition for ever-scarcer jobs. That dynamic, in turn, could drive down wages and increase economic inequality.

Juárez says his parents, who own a window-installation shop in the capital, see the danger that may presage for Mexico. They are concerned about what robots mean for the future of manual labor, as just one in five Mexican workers has a college degree. Indeed, the World Economic Forum says Mexico’s biggest challenge is that education falls short and the existing workforce needs retraining. Juárez tells his parents that people will need to change as the technology does, but that may be much easier said than done.

Left Behind, Scaling Up

“We feel like the robots are replacing us,” says Mariano Bueno, who worked for 27 years at the Volkswagen assembly plant in Puebla, about 300 miles southeast of San Luis Potosí. The factory, he says, seems to be producing more vehicles while employing the same number of workers.

Bueno’s first job at the factory, in 1989, was in the metal works. Everything was manual. The smelting, the painting, and the welding were done by hand. Iconic models – the original Beetle, Golf, and Combi – rolled down the lines. Bueno remembers that two workers would insert each sheet of metal, while another two would pull it out. Four stations were manned by a total of 16 workers, ironing and cutting. Today, he says, mechanical arms do the metal work, while a handful of humans supervise. Each robot eliminates three or more jobs, he estimates.

In 2016, Bueno became a full-time union representative at the factory. The union fights to secure alternative jobs for workers replaced by robots, even if it means serving food in the cafeteria. Processes like assembly and smelting continue to use manual labor, Bueno says. Those jobs require human instinct: “A robot is square. It does what it’s programmed to do, and that’s it,” he says.

Younger employees at the Volkswagen plant generally see the robots as a positive, since they boost productivity and reduce errors, says Antonio Espinal, a sociologist at the University of Guanajuato who has interviewed dozens of VW Puebla assembly workers in recent years. Workers also receive productivity bonuses for turning out more cars with fewer mistakes.

“Younger workers don’t have a comparison base,” Espinal says. “They’re accustomed to the robots.”

Back in San Luis Potosí, Integra Automation’s Palencia believes that Mexico can scale up. But the hurdles to more sophisticated manufacturing are real. He sees education as antiquated, centered on rote learning, and infrastructure that is lacking. But if he can do it, so can others.

Palencia is the son of subsistence farmers from a mountainside town in central Mexico. Toward the end of elementary school, he faced a choice: work the fields every day or commute two hours each way via buses to attend school in the nearest city, Toluca. He chose school. Weekends were spent planting and picking beans, corn, and zucchini. Then he got a scholarship to attend college in Monterrey, graduating with an engineering degree. Adversity, he says, in true engineer style, became his “motor.”

Saddled with debt after college, Palencia and a partner launched Integra in 1995. They chose to set up shop in San Luis Potosí, where industry consisted largely of a few family-owned companies. They knocked on a lot of doors, but locals weren’t interested in increasing productivity. One prospect, he recalls, pointed to a machine that had been working, in his opinion, just fine since the Mexican Revolution, in the early 20th century. Now many of these same businesses see the writing on the wall, he says. They urgently want to automate.

The constant assembly line changes at automotive plants have proven a boon for robot integrators like Integra. The work is steady. Several Integra clients did postpone projects after Trump won the U.S. presidency on the promise to move factories back from Mexico. A few more paused their automation plans after trade talks soured and Trump unleashed steel tariffs in May.

From Palencia's perspective, the trade talks are out of his hands. He will keep marching forward. But he agrees with Earl Anthony Wayne, the former U.S. ambassador to Mexico, who says NAFTA should include a chapter or a forum to discuss workplace development and share best practices. Palencia feels that every society – and, perhaps, a continent with an economy as integrated as it is in North America – must take a holistic approach to the evolution, contemplating the human and environmental impact of new technologies, in addition to the economic benefits.

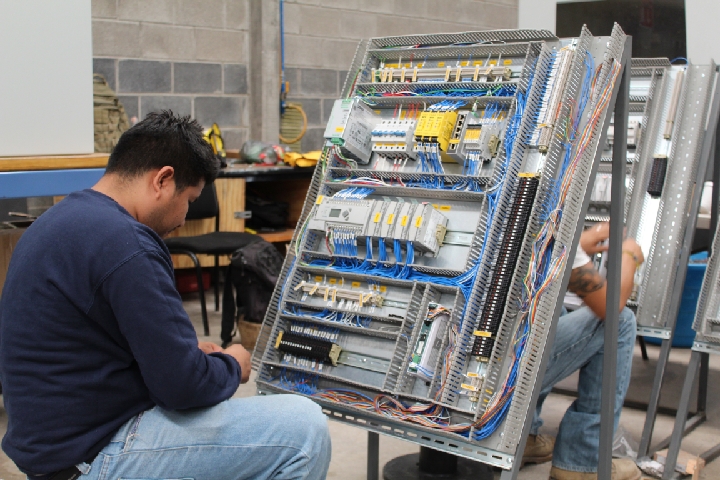

In his adopted city, the reality is that skilled labor is so scarce that clients began poaching Integra’s employees. Palencia turned that into an opportunity; he started a 40-hour training program to prepare workers for higher-skilled tasks and then hire them out. He can’t change the whole country, he says, but he can give a few hundred Mexicans a fighting chance at gainful employment. The robots are coming, he says, and “There’s no turning back.”

***

Amy Guthrie (@Amy_GuthrieDF) is a Mexico City-based contributor to the Financial Times and the Associated Press. She was formerly a staff reporter for The Wall Street Journal.

Photos courtesy of the author

Cover photo: Integra employees assemble control panels for a client.