Fall 2016

“A Tribe of Exhibit People”: American Guides Recall Soviet Journey

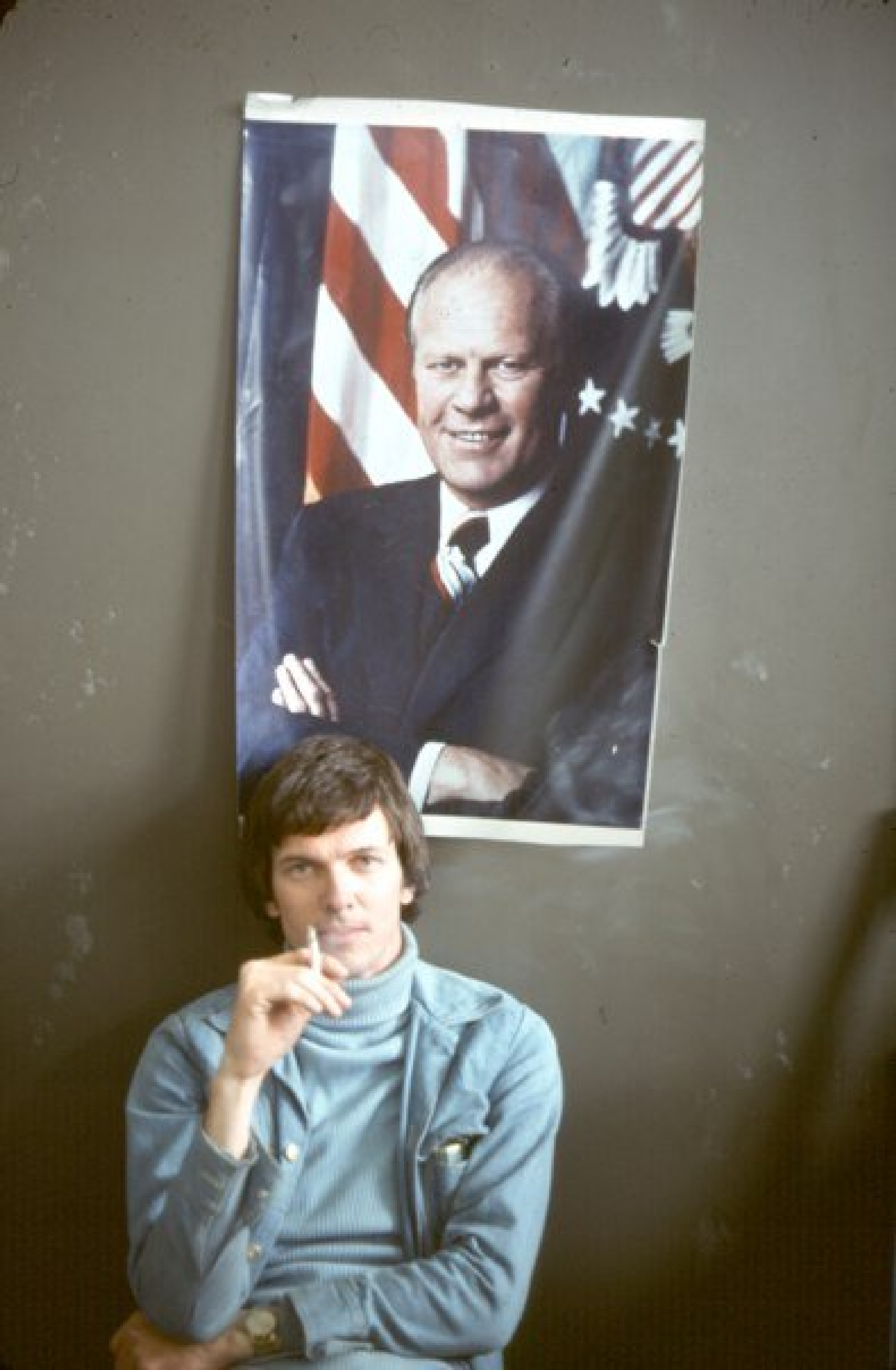

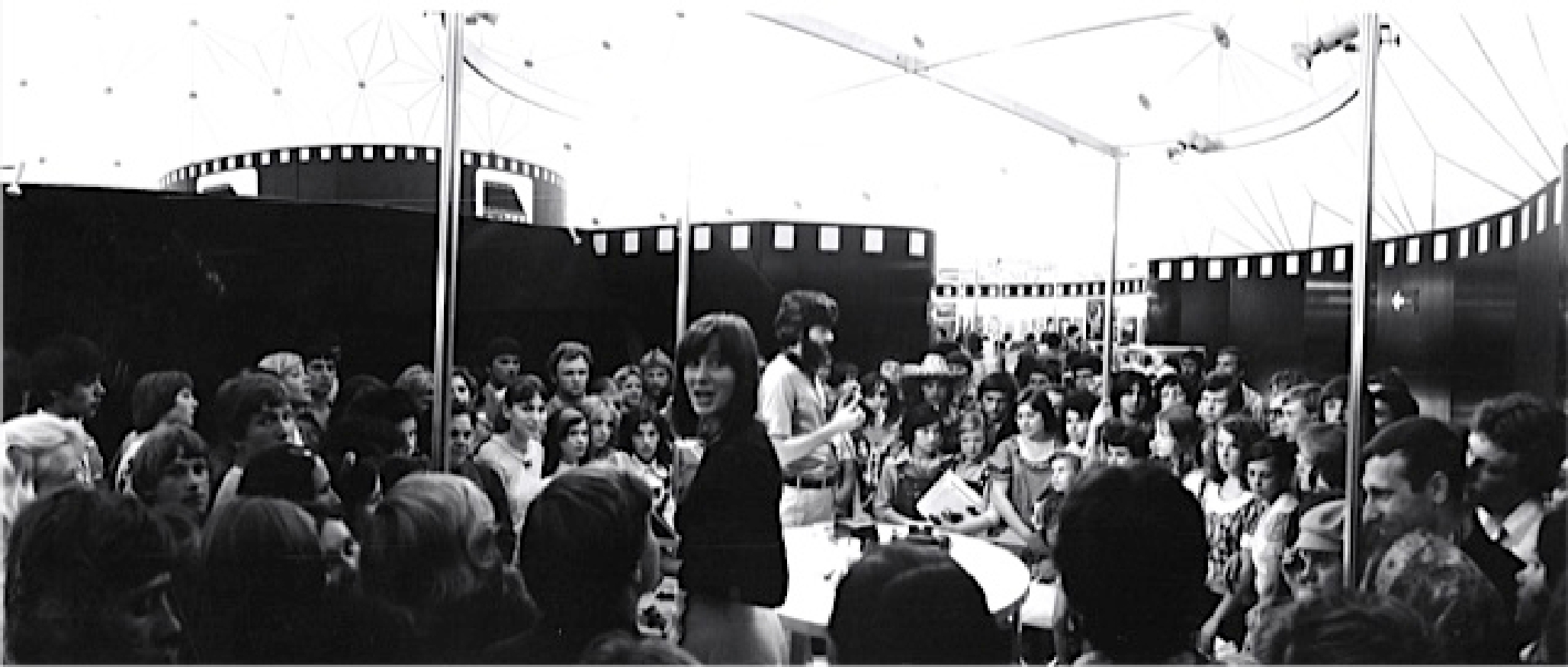

Forty years ago, a group of young Americans traveled to the Soviet Union to serve as guides for the Photography USA exhibit, one of dozens of traveling shows organized by the U.S. during the Cold War. Here are their recollections, in their own words, of those eye-opening days.

In 1977, a group of adventurous, young Americans traveled to the Soviet Union to serve as guides for the Photography USA exhibit in the city of Novosibirsk. The display was one of dozens of traveling shows organized by the United States Information Agency during the Cold War to demonstrate American technological advances and ways of life to the Soviet public. Many of those who served as Photography USA guides went on to pursue distinguished careers at the State Department and other U.S. government agencies.

Forty years after the exhibit, here are the recollections of several former guides, in their own words – from their first impressions of the USSR to the unanticipated questions posed by exhibit-goers (see rare photos here), and from KGB harassment to the lasting impact of the experience on their lives and thinking.

Gail Becker: “You Had to Have People Who Were Engaging"

"You had to have people as guides who were engaging. They had to be able to deal with thousands of people a day. It could be quite daunting.

"They were given various kinds of political briefings. And they were given subject area content too. And then they got briefings on American issues. However, they were told that if this is something you personally don’t agree with, you can state that. So the mantra was that you have to be able to explain the official American position. But if you don’t personally agree with it, you can state that. And particularly during the Vietnam war...that was particularly an issue, because so many young people didn’t support the war in Vietnam."

John Aldriedge: “They Wanted People Who Could Think on Their Toes”

"USIA wanted a broad spectrum geographically around the country. They wanted half men and half women, and Native Americans and African Americans. They had to speak Russian, but that was not the number one thing. They wanted people who could think on their toes.

"When we interviewed a future guide, we’d ask them, 'How much is a kilowatt hour of electricity?' or 'Why do you kill your presidents?' [These were] the kind of questions we’d get over there. We wanted to see the reaction. Some knowledge of America too, to see that they [were] not too ignorant about what’s going on in this country."

Roland Merullo: “The Security Briefing Scared Me a Bit”

"There was some security training, where they warned us that the KGB might try to do something, to compromise us. I felt intimidated. I was worried; I felt like we’d be constant targets for the KGB. The security briefing really scared me a little bit. It made me a little hyper-conscious of the things that could be done to us."

Margot Mininni: “They Chose All Types of People”

"The interesting thing about the in-person interview was that we were all studying the Soviet Union, but they wanted people who could speak about American stuff. They wanted to know that you knew your American history and Congress, etc., which defeated a lot of people who were focused on Soviet stuff. But they also wanted to see that you had a sense of humor and you were able to relate to people. It was a good mix: you had the quiet person who could listen, and you had really good Russian speakers, and then the rest of us stumbling about."

Michael Hurley: “We Were Told to Give Our Own Opinions”

"There was no ideological training for the guides. There was an effort to say, “You should try to be positive.” But clearly, clearly, the message was, 'You’re out there representing your country, but you’re also representing your own opinion.' USIA’s mission was to say, 'Here’s the world the way we see it.' But it wasn’t supposed to be a unified view."

Gail Becker: "It Was Like a Traveling Circus."

"The scale of this operation was huge. It was like a traveling circus.

"Inside USIA, it was a fairly small group: project director, myself as a project officer, and one or two other people. And then we had a logistics section. These exhibits traveled in ten foot containers, and you could have 20 of them. It was huge, because we had to send not just the exhibit. We [also] had to send toilet paper for 30 people for 2 months. At some point, we began to send, with each exhibit, either a nurse or a doctor. And it wasn’t just the guides; we also had administrative staff that went with them.

"So the budgets were huge. Toward the end, in the 1980s, it cost something like $20 million to develop an exhibit, ship it, staff it, and have it travel to 6 cities. It was big money. And there was a strict timeline. Everything had to be in a Brooklyn warehouse by a certain date in order to make the shipment. It went to Europe. Then it was trucked or delivered by train from whatever seaport it landed [in] to their first city.

"The brochures were a separate project. This [was] before electronic transfer, so you had to ship the text for printing. We had a USIA printing plant in Beirut, Lebanon. Then it was attacked, so we began to use Manila. All the brochures were printed there. Of course, once the Berlin Wall fell, Congress was very happy to pull that money back.

"Once the Soviets agreed to an exhibit, they honored their agreements. But they put a lot of obstacles in our way. Before we containerized the exhibits, which began in the 1970s, we used to send them in cases, and cases would [go] missing. Every exhibit had a library with it that would have books on a particular theme, and the customs officers would actually look at all the books. Some of them we had to take out."

John Beyrle: “It’s How I Started to Learn How to Be a Diplomat”

"Everybody focuses, and rightly so, on the kind of “software” part, which [was] the guides talking to the Soviets. But the “hardware” part of it, the logistics, the amount of work that had to be done to move that exhibit in 25-35 foot containers from, say, Leningrad to Dushanbe...Just imagine that: all of the clearances, all of the work.

"On Agriculture USA, I was a GSO [General Services Officer] in charge of logistics. It was very interesting just from the standpoint of how the Soviet system worked, especially the customs system. Everything had to come in and be cleared by customs. My main preoccupation was with shipments that would show up from Washington without any advance notice. They were the ones that always elicited a lot of interest from the tamozhniki (customs officials). So I would have to form a relationship with the customs officer.

"It was really how I started to learn how to be a diplomat, I think. I learned that if I could get a customs officer to somehow trust me, or [to] see me as a trustworthy person or someone who at least kept his word and knew what he was doing, it would be easier. We could get the container or the shipment out of bond faster than if he didn’t. And in some cases it just depended on the personality of the individual too."

Gail Becker: “They Had to Be Self-Sufficient”

"The exhibits were always designed by American designers, but because of the cost of shipping the components, we’d bid the construction out to American and European fabricators. It usually was a German or Italian company [that] would do the work. So every time we went to a new city, a crew that knew how to put it together would come in. We also had a support office in Vienna with technicians who worked from there. We’d send one or two technicians with each exhibit, because things had to be constantly repaired. Once out in the field, they had to be self-sufficient, and it was a pretty well-oiled machine by a certain point. And the guides all had to help to assemble the exhibit; it was part of the job."

Robert Houser: “I Was Excited to Go Behind Enemy Lines”

"I came in on Scandinavian Air, and my earliest impressions were just how barren the farmlands were below. It wasn’t like [the] cultivated fields that we’re used to here. It just looked very unkempt.

"As soon as we crossed the border the stewardesses started saying that photographs were not permitted out the window. When I landed at the airport, it was the old terminal, and the 'Moskva' letters were still there on the roof. It was fascinating to me that it was a nice Art Deco design. Of course, I was fascinated to see the armed military at the passenger terminals as we entered. I was also fascinated that they asked me, 'What do you have with you?' The things they feared most were books. They asked, 'What books do you have?' I knew I was entering a police state; I knew that I was entering a cold war foe. And I was just excited to go behind enemy lines and see life."

Roland Merullo: “Moscow Was Enchanting for Me”

"Moscow was enchanting for me. I remember riding from the Sheremetyevo airport. We got on a bus at dusk or shortly after dusk and rode into the center of Moscow. And it was so exotic to me. The wide boulevards with very few cars on them. Only one or two commercial buildings that had generic signs like 'bulochka' ('bread roll') or 'myaso' ('meat'). It was really moving and memorable to me.

"We stayed at the Metropol Hotel, which in those days was really a wreck. It was in terrible condition. It still had a little bit of its faded pre-revolutionary glory. But the fountain in the dining hall didn’t work, the waiters didn’t wait on you, [and] the rooms kind of smelled of shellac. It wasn’t dirty, it just needed repair. But we were right near Red Square, and it [was] so exciting to me to actually see the Kremlin and the changing of the guard.

"Then we were flown to Ufa, which was pretty bleak in those days. There was one store we could walk to that had very little in the way of produce on the shelves. I remember the young boys; they would see us at the store...They would wait outside, and they would say, 'Zhvachka, zhvachka, zhvachka' ('Chewing gum.'). They wanted gum, and they thought we had it. Sometimes the adults would say, 'Spichki?' ('Matches?'), just as a way to start a conversation."

Margot Mininni: “There Were These Little Exhortations on the Buildings”

"I first came to USSR in 1973 and worked as a nanny at the embassy. I had Sundays off, and every Sunday, I did an excursion in Moscow. In those days, in Red Square, when you walked around, there’d be military music playing. Saturdays and Sundays were people’s time to gulyat (go for walks).

"There were all these lozungi (slogans) – all the little exhortations on the buildings. You’d walk around, and you’d have all of those everywhere, in red, with the exclamation points, like 'Slava trudu!' ('Glory to labor!'). I didn’t know what a lot of those words were. Like 'Sovyetsky Soyuz – Oplot Mira!' ('The Soviet Union is the bulwark of peace!'). I didn’t know what oplot was. So you learned a lot of words that way. And you’re walking everywhere in Red Square, and there are people in uniform, and people walking hand-in-hand, and this music playing. And I thought, This is exactly how I imagined how it would be from propaganda in the United States. It was very military, very great, and I just loved it."

Tom Bickerton: “The Bread Store Was an Amazing Place”

"We were as fascinated with how they lived as the people who came to the exhibit and wanted to know what life was like as American university students. The bread store was an amazing place. I grew up on slices of white bread here in the States. And in Novosibirsk, they had this huge bread store and every imaginable kind of beautiful loaf just spread all over. And to make it even more fascinating, you had to stand in three lines to buy a single loaf of bread."

Margot Mininni: “Everybody Was Listening to Vysotsky”

"When I went there first to work as a nanny at the U.S. Embassy in 1973, I dated a guy. That was so wrong, because I worked for an American military attache, but I hung out with him and his friends. He was very working class. And through other nannies, I met people involved in samizdat and a lot of literary people. I met a lot of them. Nadezhda Mandelstam was still alive. The problem is that my Russian in ‘73 was very basic, and there were these fabulous literary conversations with all these authors going on around me. But what did I know? And everybody was listening to Vysotsky, which I, at the time, couldn’t understand. Later, I could really understand why people liked that music."

Michael Hurley: “You Didn’t Have Better Tomatoes Than in Russia”

"I’d never seen an abacus. And these were the days in [the] USSR when cash registers were coming in. So you’d go into a grocery store, and there’d be an electric cash register...The clerk would still be using the abacus and would ignore the technology. We were struck, of course, by the lack of...variety of goods. There would be the pickle aisle, a cabbage aisle; there would be a bread aisle, and not much else. On the other hand, we were also struck with how good the tomatoes were. You just didn’t have better tomatoes than in Russia, because, of course, they [were] naturally grown."

Robert Houser: "Nixon on the Moon"

"I remember one young boy in Alma-Ata asking, 'Is it true that Nixon went to the Moon?' And I thought, Wow, there’s some rumors going around here."

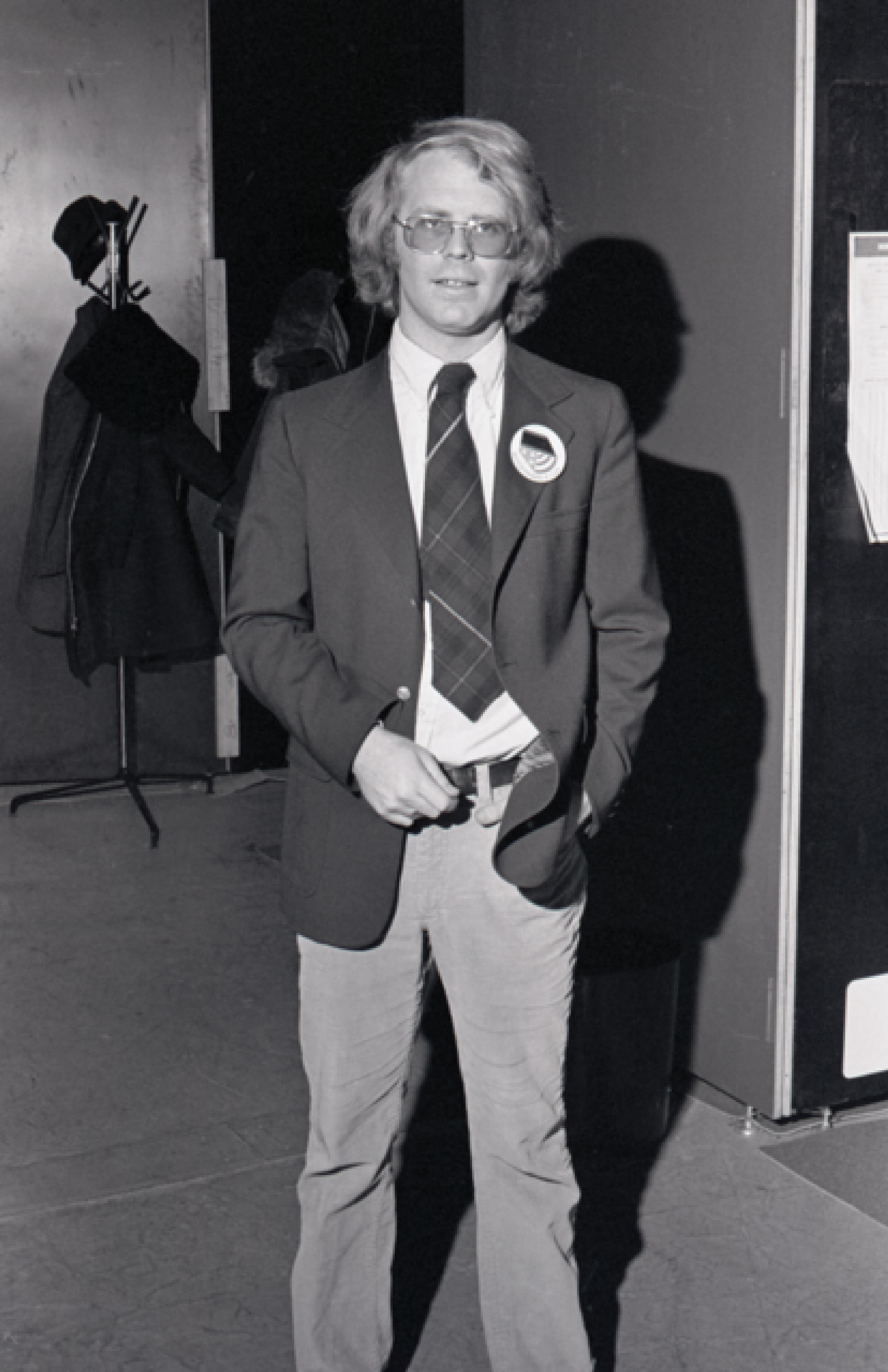

Tom Bickerton: “95 Percent of Questions Were About Life in the U.S.”

"When we were on the floor of the exhibit, and Russian visitors came, maybe 5 percent of the questions would be about photography, and 95 percent would be [about] life in the U.S.. The first question would usually center on the economy. The second one would be about crime in the US. And the third one would be, 'Does everyone have guns in the U.S.?' We tried to straighten them out on all three questions."

Thomas Robertson: “Opportunity for a Broader Contact”

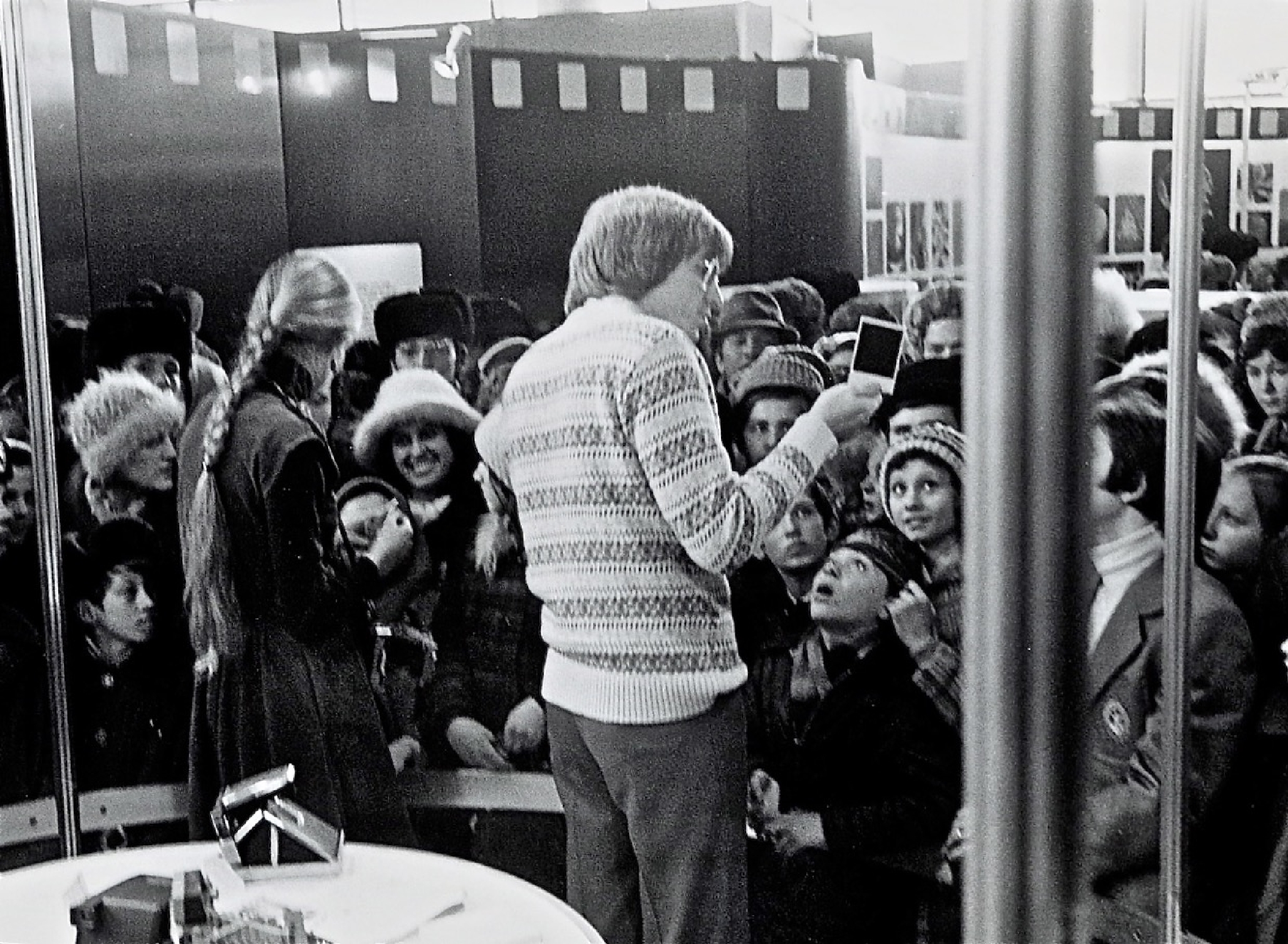

"The exhibit was an opportunity to open up a small part of the Soviet Union to a little piece of America. But the vast majority of the questions we got on the stand had very little to do with the substance of the exhibit. Of course if you’re working on the Polaroid stand, everybody was always [saying], 'Snimite menya, snimite menya, pozhaluista!' ('Take my photo, take my photo, please!')...Everybody wanted to see how it [worked].

"But when you got into a discussion, it was all about, 'A skol’ko vy zarabatyvaete? A skol’ko sredniy rabochiy zarabatyvaet? A skol’ko u vas ploshchadi v vashey kvartire? A kak vy platili za vyssheye obrazovanie?' ('How much do you earn? How much does an average worker earn? How many square meters is your apartment? How did you pay for education?') In a sense, the exhibit was an opportunity for a broader contact with the Soviet public in a friendly, people-to-people way."

John Aldriedge: “Why Are You Bombing Our Sailors in Haiphong Harbor?”

"The visitors were always trying to compare to make it understandable, and sometimes it was hard. I wasn’t prepared for that at the beginning. Like, 'How many square meters [are] in your house?' No American would have an answer to this question. We measure our homes in the number of bedrooms. So all our staff got good at converting square meters to square feet and trying to guesstimate.

"Or things like, 'How much is a kilogram of meat?' Well, you’ve got two problems here. One is, we think in terms of pounds. Two, I don’t think any of these kids who were guides bought much meat. Their parents bought meat, or they got it in a cafeteria. They were all very young. I started when I was 21 or 22, and I hadn’t been out doing adult things, so I couldn’t really answer a lot of adult questions.

"Or they’d ask, 'How much is a kilowatt of electricity?' I’d sometimes send a cable back asking, 'Do you have any idea how much is a kilowatt of electricity?' So somebody back in Washington had to get out their electric bill and try to figure it out.

"Sometimes the visitors would have a question like, 'Why are you bombing our sailors in Haifung Harbor?' They’d make charges or be critical."

Roland Merullo: “You Must Be a Son of a Rich Capitalist”

"It was very arduous to be a guide, very intense. You were on the stand six hours a day between 9 and 6. We had an hour on, an hour off, two hours on, two hours off. We had a little place where we could eat lunch. But when you were on duty, you would stand at some place at one of the displays, and you would be surrounded by a knot of 5 or 10 or 15 people pressing in closely on you, asking you one question after the next after the next for an hour.

"The questions were, sometimes, very simple: 'How much does a loaf of bread cost in America? Do you have any brothers and sisters?' The famous question was, 'What’s your favorite rock group?' That’s the question kids would ask. That was a big question for some reason. There was a lot of interest in Western music.

"And then the questions could be much more pressing: 'Why can’t black people and white people sit down at the same table in America? Why are the police always beating people in America? You must be the son of a rich capitalist; otherwise, you wouldn’t have been able to go to college.'

"I’d show pictures of my house, and they’d say, 'Oh, you’re rich! That’s your house? That’s a private house?' My house was a very modest house, and people would accuse us of lying.

"KGB would send in provocateurs, who we could identify very easily. They would ask very angry questions: 'Yeah, that picture of a supermarket, that supermarket is for the rich sons and daughters of capitalists. That’s not the kind of supermarket anybody could go in to!' Or they’d say, 'You’re lying; you don’t know anything about us!' There’d be 6 hours a day, 6 days a week of that kind of exchange, and that was exhausting."

Kathleen Rose: “I Want to Talk to a Real American”

"I was struck mostly by their attitudes about us. First of all, I cannot tell you how many women...commented on how late I’d gotten married: 'Why? You were probably an old maid…' I got married [at the age of] 27. Nearly all the women on the exhibit were not married, and so they got constant [questions]: 'Where are your babies? Why aren’t you married?' This was even true in Moscow. I was really intrigued by that.

"I was constantly asked about my ethnicity. I was constantly asked, was I Georgian? Was I Chechen? Was I Armenian? I would say, 'I’m stoprotsentnaya amerikanka' ('I’m one hundred percent American.'). But they would say, 'No, but what are you really? Your proiskhozhdeniye?' ('Your origins?'). I remember one man said, “There is a 'namyok vostoka' ('a hint of the Orient'). Finally, I would say, 'Well, my father is Greek, and my mother is Irish.' There was a weird obsession with it. And one man said to me, in Moscow, 'Well, I want to talk to a real American,' and pointed to a guy on the exhibit who was like the poster child for WASP Americanness.

"We got a lot of comments about our appearance, and how skinny we were, and how we dressed. 'This is an exhibit. You are representing your country. You aren’t dressed properly!' There was this sort of an idea that you should have your little string of pearls and your sweater set… Very conventional ideas, maybe more like [the] 50s, of how women should dress and what was dressing up."

Thomas Robertson: “There Was No Subject That Was a Taboo”

"When I was on an exhibit in ‘75, Vietnam had just ended. And if you went around the exhibit, you found guides who would defend what we did in Vietnam, and then you would find guides who were violently opposed to our activity in Vietnam. The Soviets, of course, were not very comfortable with public discussions of political issues. And to find Americans who had been hired by their government to work on the exhibit, who were against American policy, and [who] had no problem, at the exhibit, to express that opposition – that was pretty novel for them. That established a connection of Russians or Soviets with the guides. We got into discussions of everything: World War II, dropping the atomic bomb. There was no subject that was a taboo."

Kathleen Rose: “Every Day, You Criticize America, and the Next Day You Are Still Here”

"I was so impressed with the [kinds] of questions people asked, what they were curious about, and how much they worked at getting information. I felt like people had a whole different and very impressive mindset. There was this real desire to figure out what [was] important in life, what [mattered].

"I felt like a 900-pound gorilla in the room was that the exhibit was like a Potemkin village. It appeared to be about photography, but what it was about was [this]: 'Look at the way we live in America. Eat your heart out!' And so here, my strategy became… I wasn’t going to be anti-American; I was going to be truthful.

"So when someone would parade their picture of a Safeway market around the exhibit, I would say: “Ah! But you haven’t had an American tomato. Let me talk about the downside of...American agricultural production.” So I would talk about these tomatoes that were more like tennis balls.

"Or I would engage them in a debate about what are the risks of a free society, and I would go on and on about the problem of guns in America. I wasn’t there to trash America, but I felt like... I want to give you a real picture. I don’t want to patronize you, and I don’t want to be a propaganda machine. I want a real, honest dialogue about the ups and downs of a free society.

"And the hilarious part was… At one point, there was a big crowd, and this guy said to me, “Every day you criticize America, and the next day you are still here. We are so impressed.'"

Kathleen Rose: “It Was Overwhelmingly Exhausting”

"I considered my Russian not to be up to snuff. It’s one thing to study it in school; it’s another thing to be dropped into it like a fish in the sea, and then to have people talking a mile a minute. I remember, on the first day, being in front of the photography dark room with a red glass, so they could see in, and a woman asked me, 'How do you get the pyl (dust) off the negatives?' I didn’t know the word pyl, and I was like, 'What?' And she said, 'Well, why are you here if you can’t communicate with us?'

"It was an ordeal. You [were] up on the stand six days a week. Your Russian [got] pretty good after a while, but it was so overwhelmingly exhausting, because you would get into these discussions...You [were] not speaking your native language, and people [were] asking these complicated questions. I would take these ten minute breaks and hyperventilate in the bathroom. And then I would go back and start again."

John Beyrle: “I Would See People, Sometimes, Really Depressed in the Guides’ Lounge”

"It was a revelation to me, as it was to everybody else, what you were dealing with when you spoke at length to a vast cross-section of Soviet people. The thing that stands out in my mind was the experience that happened very early to me, in Ufa, the first city of the exhibit. I was standing on the floor having an argument, as you often did. You kind of got into arguments with people, because they were saying things about the United States that you just knew were not true. They were repeating the propaganda that they were being fed by the Soviet press, by the agitprop apparatus. And you were trying your hardest to marshal facts and speak intelligently about why what they thought wasn’t quite right. It wasn’t always completely wrong, but it was distorted.

"In one case, I remember, it was probably at the end of my two hours, and at the end of that period, you were just exhausted mentally. You were like a fighter in the 12th round who could barely keep his arms up sometimes. And you were, at that point, looking for sympathetic people in the crowd to help you fend off the agitators, the komsomoltsy (Komsomol members) who would come in.

"So I remember this guy who said, 'America is an imperial, colonial power. You colonialists…' And I was just kind of staring at him blankly. And another guy on his right broke in and said, 'Da vy nichevo ne ponimaete ob Amerike! Amerika nikogda ne byla kolonial’noy vlast’yu.' ('You don’t understand anything about America! America has never been a colonial power.') And he began to talk about the history of the United States in a way that, I just thought, Wow.

"Maybe he was a professor of history; I have no idea who he was. But I remember being absolutely struck that this guy knew more about American history than I did. It wasn’t that I didn’t know that America was never a colonial power, but he knew things that I couldn’t have just pulled out, even if I had been speaking English. And I remember thinking very early on, This is quite a society here.

"Because, number one, you [had] people who [were] obviously intelligent and well-educated and, in some cases, [knew] more about my own country than I do. And second, he [was] willing to stand up and push back against this guy, who [was] giving me a hard time. And who knows where that might [have] led for him? That might not [have been] a good thing for him or his career.

"I think he just felt sorry for me. He saw that I was about to be knocked out in 12 rounds, and he rushed to my defense. I will never, ever forget that feeling. It took me to a whole new and deeper level of understanding of what I was going to be dealing with for the next 6 or 7 months on the exhibit.

"That experience would repeat itself numerous times. And you would learn, as a guide, as you got more experienced, when you were on the ropes. When the agitatory (the agitators) had the upper hand and were dominating the conversation, you would look around in the crowd for people who could be potential sympathetic voices. You could almost feel, by looking at their faces, who was unhappy that you were being subjected to a grilling by these agitatory. Maybe they wouldn’t jump to your defense like that first guy I just described. But if you appealed to them and said, 'Da neuzheli vy tak otnosites’ k svoim gostyam? Ya zhe gost’ v vashey strane!' ('Are you really treating your guests that way? I am a guest in your country!')...That was immediately an opening for someone else to say, 'Da bros’te ob etom! Ya khochu o drugom sprosit' ('Enough of that! I’d like to ask about something else.').

"You did this for six months, six hours a day, six days a week, and just as a matter of self-defense, you got to be pretty good at finding those people who would change the subject for you. A lot of times these guys wouldn’t let you change the subject. They’d say, “Net, net, vsyo-taki o bezrabotitse vy nichevo ubeditel’novo ne skazali!” ('No, no, you still haven’t said anything convincing about unemployment!') even though you [had] just talked for the last 15 minutes about how 'Est’ posobie po bezrabotitse, a posobie po bezrabotitse – eto gde-to 200 rubley v mesyats.” (“There are unemployment benefits, and that’s around 200 rubles per month.'). It was always, 'Ooo! Ne mozhet byt’ takovo!' ('Ooooh! That’s impossible!') And you would look for that babushka who wanted to talk about your parents or your family or your home town.

"I would see people, sometimes, just really depressed back in the guide lounge. They would come off and sometimes, they would be really mad...They would hyperventilate, and worse, there were tears."

Tom and Gerri Bickerton: “They Wanted Personal Stories”

TOM: "The great thing was that if the people around you saw that you were struggling with the language, they were so protective and helpful, and they were giving you hints. And even if you [bungled] it completely, they [loved] your effort. It was just a pleasure to go out there and talk to these people every single day."

GERRI: "And they would really listen and judge each guide as different personality types. Like they would say to Tom, sometimes, 'You are a very kind man.' They picked up on each personality. And they certainly wanted to know how daily life [was] for you, about your families, how you [lived]."

TOM: "They wanted personal stories."

GERRI: "They wanted personal stories, because they weren’t getting those stories. All they were getting was our headlines. If you go by those headlines, the United States is a terrible place to live."

Margot Mininni: “Why Do Your People Shoot Your Leaders?”

"They did send professional provocateurs to the exhibits. One time, they were talking about our history of gun violence and the fact that Kennedy had been assassinated, and Martin Luther King. And one young guide got asked, 'Why do your people shoot your leaders?' And she said,'Why do your leaders shoot your people?' That was her come-back. And sometimes, people in the back of the crowd would shake their heads at the provocations, or they’d come up later, and they’d say to us, 'Molodtsy!' ('Well done!')."

Roland Merullo: "What Impressed People the Most"

"Two things impressed people the most. One was the level of wealth that we took for granted. I remember we brought cases and cases of Pepsi to drink, in cans. And I remember one of my friends looking at the Pepsi can and saying, 'Can I take this home?' Because it was beautifully designed, and the world that they lived in, it was a very bleak world; it was not filled with beauty.

"And the second thing was the fact that we could speak openly. Nobody ever told the guides, 'Look, you can’t say this or that; you have to say nice things about America.' And we were all different. Some of us were very liberal; some of us were very conservative. Some of us were very critical of America; some of us weren’t. And so, people would go from stand to stand and listen in and have different conversations. And they’d say, 'Kathy Rose just said this, and you say that.' And I’d say, 'Ah, well, we don’t agree. It’s not like there is a party line.' And I think that made a big impression on people."

Michael Hurley: "The Attitude Shift from the ‘70s to the ‘80s Was Huge"

"One of the things that changed hugely was the attitude shift from the ‘70s to the ‘80s. In the ‘70s we used to get propagandists, agitators...They’d come through, and they’d say, 'Why do you hate black people? Why do you have poor people?' And you’d have to keep up in Russian, and it would be a public confrontation. And they wouldn’t give up. They would just keep pounding away: 'Isn’t it true, isn’t it true...'

"And in the 80s, when I was there in [Gorbachev's] time, I was the Embassy person responsible for the exhibits...The difference was almost an embarrassment of riches. Then people would come through who were genuinely interested in making an anti-Soviet statement through you.

"They would say, 'Isn’t it true that you can buy 25 different styles of jeans at any store in the United States?' And you would say, 'Yeah, but you wouldn’t have the money.' It was sort of like, 'Isn’t it true that the streets are lined with gold in America?' And I would say, 'Well, not really.' You would start backing up."

Roland Merullo: “The Questions Changed Noticeably Over the Years”

"The kinds of questions that were asked had changed noticeably over the years. There was a comment book, where visitors could write their comments as they left. In 1977, the comments would be, 'Very beautiful. We enjoyed speaking with Roland or Kathleen, etc.' And other people would say, 'It’s all a lie; I don’t believe it for a minute.' But by 1989… I remember one comment in particular: 'Vy zhivete na lunye; my zhivyem v govnye' ('You live on the Moon, we live in shit.').

"I remember very well this one young woman in Moscow in the late 80s. [She was] probably 30 years old or so, very attractive, very intelligent. She said, 'It will be five hundred years before we live the way you live.' And I said, 'No, look at all the progress you’ve made. The country is opening up: glasnost, perestroika...' And she looked at me very hard in the eye and said, 'Pyatsot lyet!' ('Five hundred years!'). And she walked away. That never would have happened in public in 1977."

Roland Merullo: “This Might Be Their Only Opportunity to Meet an American”

"A lot of times – surprisingly, given the political climate – people would invite us to their homes.

"At least once or twice a week, we’d go to homes for dinner. The people didn’t want anything. They knew that this might be their only opportunity to meet an American. If they liked you, if they sensed that you were a decent person, they’d invite you. Their homes were very humble. The people would spend a lot of money to make a really nice meal. And we’d sit around and drink vodka and talk for hours. And sometimes, if they had a car, they’d drive us back to the hotel, or they’d accompany us on a subway or tramway or something. Sometimes, those friendships really lasted."

Roland Merullo: “There Are No Airplane Crashes in the Soviet Union”

"Most people were completely propagandized. But if you got them alone, they would say things. When I was a GSO in Irkutsk, I used to take people to the airport. And the Soviet propaganda line was that there were no airplane crashes in the Soviet Union. We would argue with them, and we would say, 'Look, it’s unrealistic.' And they would say, 'No, no, no, it has never happened; [it] doesn’t happen here.'

"But there was a woman at the airport who worked there, and we’d become friendly with her...We would drive people to the airport and pick them up, because we were continually having guests come from America; somebody from USIA or the State Department would come for an official event.

"And this woman said, 'Sometimes, the planes take off, and we never see the pilot again.' The family members of the passengers would come and say, 'My sister got on the flight to Tomsk, and I never heard from her. What happened?' And they would have to say, “Well, go see the police.” And the police would say, “Your sister is no longer alive, but don’t tell anybody. She died in a plane crash.”

Margot Mininni: “You Would Have This Great Drinking and Talking into the Night”

"When we met with people, they would feed you this incredible meal, and God knows where they got the food: standing in line or from under the counter. They would spread the spread, and you would have this great drinking and talking into the night. Sometimes, you worried if someone was listening. And for Americans it was very exciting. We were not terribly worried about who was listening to us. You just thought, Oh my God, I’m here; I’m in the middle of the Soviet Union. I’m talking to these people, exchanging experiences. It was heady, intoxicating. But you also were touched by the warmth of the people, by their sacrifice. You knew that if they were serving you bananas...Where the heck did they get them? They could have enjoyed them but they gave them to you."

John Aldriedge: “There Was a Lot of Harassment" "Sometimes you could tell that you were [being] followed or watched. Since we didn’t do anything wrong, we didn’t think too much about it, but there was a lot of that sort of harassment. Some of our Russian friends got harassed. And some people would get scared and would be afraid to see us, but others would just get more careful. They would say, 'Pozvonite mne iz avtomata.' ('Call me from a phone booth.'), or 'Vstretimsya na tom meste.' ('We’ll meet at such and such a place.'), not to draw a lot of attention. It was bizarre, and it was nerve-wracking sometimes."

Roland Merullo and Robert Houser: “Don’t Ever Come Back Here Again”

ROLAND MERULLO: "During our training, we were told, “Don’t ever sign anything. No matter how benign it seems, if someone wants you to sign a document, do not sign it.” This came back to us in Novosibirsk in a very important way.

"In the middle of the summer in Novosibirsk, it [didn't] get dark till very late at night. So the exhibit would close at 6 o’clock, and Bob Houser and I would go do something in the city every few days. Bob was a staff photographer, and he didn’t speak Russian, so we would often do things together.

"Our visas allowed us to travel 25 km outside of the city that we were stationed in. So one day Bob and I went down to the train station, and we looked on the map and found this little village, Krakhal. It looked like it was about 20 km outside the city. I bought the tickets. It was completely innocent. We were going to ride out into the country, [and] take a little walk. He was going to take a few pictures of some houses, and we were going to ride back. There was no other intent beyond that.

"After I bought the tickets, Bob said to me, “There was a guy behind you in the line. After you bought the ticket, he walked up to the window and asked a question of the woman selling the tickets, and he was looking at you.” I said, 'You’re paranoid; don’t worry about it.'"

ROBERT HOUSER: "I guess it’s because I’m a photographer, and I’m always looking, but I could pick out a tail almost instantly. I could just tell someone who was acting a little bit strange, watching me a little too closely, showing up several times in the background. And I picked this guy up right at the train station. He got on the train with us several cars down."

ROLAND MERULLO: "We got on the train. It was an elektrichka (commuter train), and we rode out into the country. We got off in the village, and Bob said, 'That same guy got off the train with us.' And I said, 'Ok, it’s no big deal.'

"From the train station to the town there was a dirt path. So we [were] walking along the path, and all of a sudden, this guy [appeared] behind us. He [was] a big guy, and he [was] either drunk or pretending to be drunk. I told him to go away, and he grabbed Bob from behind. I grabbed his hand and threw it off, and I said, 'Get your hands off him!' in Russian. And as soon as I touched him, these two druzhinniki (volunteer people’s guard), the guys with the red armbands, appeared and said, 'Come with us.'

"They brought us into the train station and told everybody else to leave, and they locked the doors. (It was a very small train station, a tiny little hamlet in the countryside.)

"So we’re in one end of this room with the two druzhinniki. And the drunk guy was behind them yelling at us. The druzhinniki’s took out a pen and paper and started asking us questions: 'What’s your name? Where are you from? What are you doing here? What are you doing in Novosibirsk? What kind of work do you do?' I just answered the questions honestly. And the drunk would yell at us. He was either really drunk or pretending to be drunk. It was really intimidating. It was very tense; it was a very physically aggressive questioning...Bob didn’t speak Russian, and I was trying to explain to him what was going on.

"Finally, at the end of 20 minutes or so, the drunk guy said, 'Ok, you’ve read what we have written here, and it’s all true, so now we need you to sign it.' He handed me a pen, and I was about to sign it, because it was all true. And either Bob or I, at that moment, remembered the security briefing, when they had said, 'Don’t ever sign anything.'

"So I turned to the guy and said 'Ne mogu podpisat' ('I can’t sign it.'). And he said, 'Oh, so you refuse to sign the act?!' And I said, 'Yes, I refuse to sign the act.' That was a very bad moment. And he looked at me and said, 'Ok, the next train for Novosibirsk leaves in 8 minutes. You must be on that train, and you must never come back here again.' And I said, 'Ok, no problem.' [Laughs]

"I remember Bob and I took a little walk around the block where the train station was, and we were literally shaking, because we were really scared. We went back to Novosibirsk and reported what had happened to our deputy director. And that was the end of it. Nothing ever came of it."

Kathleen Rose: “We Wanted to Know What It Felt Like to Belong”

"We had been traveling around the USSR with a U.S. photography exhibit, and Moscow was the last city on our tour. On a whim, my husband stood in line at GUM (central department store) to buy me a Soviet schoolgirl uniform for my birthday. Another guide on the exhibit admired it and bought one for herself, and we hatched a plan to put on our uniforms and wander around Moscow. We had spent so many months being foreigners/outsiders that we wanted to know what it felt like to belong...[We] hoped that in the uniforms, we just might pass as natives, given that we were only a few years older than actual Soviet high schoolers.

"We wandered around the city, arm in arm, as we had seen schoolgirls do. When we came back to the Metropol hotel, where we were staying, they wouldn't let us in. It appeared that we had gotten our wish to be taken as natives but not in the way we had hoped.

"Unable to convince the authorities that we were hotel guests, we had to request that someone bring us our passports. Finally, after much bureaucratic kabuki, we were allowed in the hotel. As we walked down the hall to our rooms, we saw our dezhurnaya (woman on duty) sitting at the end of the hall. A friendly, grandmotherly figure, she had taken us under her wing during our stay in the hotel. At the time, I thought of her as ancient, though she wasn't even as old as I am now. This time, when she saw us in our outfits, she drew herself up to her full five feet and said, 'You have no SHAME.'

"I felt so bad. It had never occurred to me that wearing the uniforms was going to offend someone. Perhaps it was the Young Pioneer scarves that put her over the top. Definitely a failed cultural experiment."

Michael Hurley: “Contradictions Leaped Out at Me All Over the Place”

"When I first went to the Soviet Union in 1972, I was 22, and one of my first questions to my Soviet language teacher was, 'How can you be an atheist when you don’t have Bibles? How can you be against something that you never read?' And her answer was, 'Well, Lenin said.' This was a woman not much older than I, a very serious and dedicated teacher, and I just wanted to hash it out with her. But she didn’t have a very good answer. I think it embarrassed her a little. Probably, she had never thought of it. These contradictions began to leap out at me all over the place.

"At another exhibit, we went to a cardiology institute. On the weekends, we requested to do excursions, so somebody said, 'Let’s go see the cardiology institute.' It’s 10:30 in the morning, and the doctors come out in their white gowns and tell us about the institute. Then the lecture finishes, and they bring out a tray stacked with bottles of pertsovka (pepper vodka). And I’m thinking, Here I am, sitting on a Saturday morning with doctors working at a cardiology institute, and we’re having vodka.

"Later on, in [the] Gorbachev years, we did an exhibit at Magnitogorsk. I was with the Embassy, and we had a meeting with [the] mayor. There was a ban on alcohol and an attempt to limit consumption of alcohol. And in the official meeting, with other officials there, he said, 'Yes, we have a vodka limitation in the city; it’s tough, but we have to get through it.' And then he closed the meeting and the three of us - he, his deputy, and I - went off and had kind of a picnic, just outside the city. And he [opened] his trunk, and there [was] a case of vodka there. And the contradiction for me was, here [was] the mayor, who, in front of his officials, [had told] us, 'Ah, there’s this ban, and no one can get vodka.' And yet [he had] a case in his trunk just for the day. Who [knew] how much he had stashed elsewhere?

"In one sense, it made me wonder how anyone thought that this country could ever be a threat. I didn’t get ahead of the pack; no one did. No one had figured out that it would fall. But there were these contradictions."

Roland Merullo: “Coming Back Was Difficult” "Coming back was a little difficult. I was very happy to be home for [the] creature comforts. The diet was very limited in the hotels and the cafés where we ate. A lot of the foods that I was used to eating just were not available. We were regularly followed [and] harassed, so to leave that and go home was a relief, on the one hand.

"On the other hand, it was difficult to explain to my family and friends what the experience had been like. It just didn’t square with the news reports. I kept saying to people, 'Oh they are really nice people. They don’t mean any harm to us.' And that didn’t make sense to a lot of people.

"In the 10 years that I couldn’t go back [during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan], I missed the language. The Soviet Union was so closed off from the rest of the world that for us, it was exotic to be in a place where everything was so different. And I felt like I could feel the history of the place, the land. And first of all, it was very beautiful. There are so many beautiful places in that country. The land just seemed to evoke the past for me.

"And I know it’s a cliché about the Russian soul, but there is a reason why it is a cliché, because I think there is a truth to it. Sometimes the West would seem not as deep, not as focused on those things. They had conversations and friendships, and I missed that aspect of it."

John Aldriedge: “A Year Passes, and Everyone’s Ready to Go Back”

"It’s funny. It was always the same: by the time we left, people would be like, 'Oh, I can’t wait to get out; I’m so glad to get home.' A year [passed] and everyone [was] ready to go back. You only remember the good parts. It was mainly good; it was exciting."

Robert Houser: “It Gave Me a Greater Love for America Than I Had Before”

"My experience there gave me a greater love for America than I had before. We have great problems here. But I still feel, with all the traveling that I’ve done, that this is the most beautiful experiment in people living together. It’s a great country in spite of all of its faults."

Roland Merullo: “It Made Me Start to Think for Myself”

"Being there was life-changing for me. It made me start to think for myself. Because I had been propagandized too. Not nearly to the same extent as the Soviet people, but I used to watch the news and think, 'These people are all unhappy, and they all hate Americans. They probably want to go to war with us. We are enemies.' But when you actually got down to the level of person-to-person, there was none of that. I’d say 95 percent of the people I met were kind and generous at some risk to themselves. I’d thought they would all hate us, we are enemies, but the vast majority of people did not relate to us that way. To realize that they were very warm and welcoming to us was life-changing for me."

Kathleen Rose: “It Threw in Sharp Relief the Bubble I Lived in in America”

"It threw in sharp relief what a bubble I lived in in America. I think that Americans do not realize how parochial and isolated they are. We came to give information and to talk about America...[However], I realized that not only did I come up short in the information the Russians wanted, but I [also] had a very parochial view of my own country, because all my information was based within America.

"I was a counterculture ‘60s person, I was demonstrating against the war, and [was] super anti-government and a real liberal American. And in my travels in Russia, I found that yes, there was misinformation about America, but there were also different perspectives about America that were valid [and] that were not our perspectives. That was a huge lesson for me.

"Most Americans aren’t very well informed. I saw the Russian counterpart exhibit in Washington, DC, and the questions Americans asked were mortifyingly embarrassing. They didn’t know anything about Russia, even though they had access to the information. So the experience of being immersed in another culture made me realize how little I had been exposed to that in America."

Margot Mininni: “You Became Very Close”

"Everybody says it’s one of the best jobs they ever had, or the best thing that ever happened to us. It’s sort of like Peace Corp volunteers...They are together, [and] they are in their 20s, usually...They go into a certain country, and they really are with the people...They are doing something useful, and it’s the most memorable thing they’ve ever done. For us, it [was] sort of like that but also like being in the army, because we were together, and we were sharing a kind of traumatic time with a group of people. You become very close. That’s why you see bonds that last over years. And I know people from earlier exhibits.

John Beyrle: “It Forges a Bond That Lasts”

"It was a unique little fraternity-sorority of people. My analogy is that it was a little bit like being in a fox hole with your wartime buddy. We were fighting a cold war, so they weren’t shooting bullets at us. So it wasn’t that intense, obviously. But there was still a kind of battle going on. With lots of rewarding moments...Don’t get me wrong; it wasn’t all bad. But those bad moments...The people who had gone through them with you could understand them uniquely, in a way that no one else could. No one in your family, no one among your friends, when you went back and tried to talk about this - nobody else understood it except the people who’d actually been through that with you. So that forges a bond that lasts."

Thomas Robertson: “We Are a Tribe of the Exhibit People”

"It was a bonding experience, and we’ve all maintained friendships over the years. We are sort of a tribe of the exhibit people. And even if you weren’t in one of those exhibits, if we find that you were in another one, you’ve already got a special connection. Because it really was a special experience. And as I said in my interview on State Department, it was one of the most effective tools we had to bring down the iron curtain and help open up the Soviet Union."

Paul Smith: “It Didn’t Push Anything Politically”

"Photography USA was a very effective exhibit, because it related to Russians on a level that they both understood and deeply appreciated. Although the exhibit focused on many American photographers and many forms of photography, it didn’t really push anything politically. For example, Technology for the American Home focused on the technology we’d built for living, which, of course, back then, the Russians didn’t have. But Photography USA related to the Russians on a level that they understood and admired, so it took a lot of the political stuff out of the conversation."

Gail Becker: “I Was Proud to Be Associated with That Program”

"I was very proud to be associated with that program for so many years. When I was in college, the thought of working for the government was not something that was attractive for me, but it ended up [being] one of the best places to work at a time when we really were making an impact. And there were so many dimensions for me personally. I had majored in Russian in college, and so this meant being connected to Russia all these years. And it’s still a passionate interest of mine."

John Beyrle: “We Are All Human Beings”

"This is a cliché, but it’s true: the whole experience was that we are all human beings, even though it kind of looked like we were inoplanetyane (space aliens) that had come in a spaceship. When people came into the exhibit, they would find out, 'They are just like us! They speak a different language, or they sort of speak our language.' [Laughs] And the more you talked to each other, the more you realized the ultimate of all clichés that has the virtue of being true: that what divides us is much less than what unites us."

Kathleen Rose: "The Preciousness of the Connections"

"I grew up in the 50s, when the total destruction of the world was potentially imminent, and we were doing nuclear drills every other week, and how scary and overwhelming it seemed. I remember sitting in my Russian class during the Cuban Missile Crisis and thinking, Wow, is the world going to end? And at that time, being in Russia...it made the connections all the more precious. The idea that we could talk to the real Russians, that we could meet these people in this way, with these countries being combatants in the world, the two major chess players."

John Aldriedge: "It Was about Personal Interaction"

"The whole idea was for the Soviets [to be] able to meet pretty ordinary Americans and talk to them. Ok, maybe not quite ordinary - they were all college graduates and spoke Russian - but a lot of just personal interaction. That was the success of the exhibit. And, of course, the Russians [were] hospitable, and so everyone [was] going to houses to eat [and] to have dinner. We always got more invitations than we could accept. We probably learned more than our visitors did."

Margot Mininni: “The Real Secret Weapon of the Cold War”

"I really believe that US cultural exchange programs - such as the Fulbright, language exchanges, and the USIA Exhibits - were the real secret weapon of the Cold War...Along with the U.S. defense policy and strength, [they] were a great part of the reason the Soviet Union fell without bloodshed. The exhibit program was really an amazing resource and tool for us, as well as from us."

Thomas Robertson: “I Saw a Change in the Soviet Propaganda”

"In the 6 years that I worked on the exhibits, I saw a change in the Soviet propaganda when it talked about problems in the United States. When we got there, they were talking about how terrible American unemployment was. I think we had a minor recession in ’75, and they talked about all these poor Americans losing their jobs.

"By the time we left in ‘78-‘79, you would notice that the attacks on the U.S. domestic political system had changed. It became more sophisticated in that they would now mention posobiya po bezrabotitse (unemployment benefits).

"At the exhibits people would ask, 'Kak u vas zhivut, kogda bez raboty?' ('How do people live when they don’t have work?'). And I could tell them, 'U nas est’ posobie po bezrabotitse' ('We have unemployment benefits.'). We’d been doing this for years...Over time, they had to deal with people that became a little bit more sophisticated, because people in Moscow, Leningrad, Alma-Ata, Tbilisi, [and] Ufa had all heard guides talk about unemployment benefits and insurance. So they couldn’t just say that Americans [were] dying in the streets because they [were] unemployed.

"Of course, Voice of America and the [America Illustrated] magazine, which were part of this triad of our public diplomacy to the Soviet Unio - all of them had articles that covered these kinds of things. But it was different hearing it from somebody standing in front of you than...reading about it or hearing about it on the radio."

John Beyrle: “How Do You Calculate the Effect of All of That?

"If you look at the total number of visitors from 1959 to 1989 - that was something incredible, like 17 million people. Those are USIA numbers. So that’s 17 million people who just had the experience. Then you had the prospekty (the booklets) that we gave out. And those were printed, like America Illustrated, on very thick paper. They lasted a very long time. When I went to Ufa as Ambassador, I met people who had met me on the exhibit in 1977. They still had their pins, and one of them even had the prospekt, which had probably been read by several hundred. I fear no exaggeration in that. It was still together; it had been re-stapled at some point - really amazing. So think of that. You had 17 million people. Every single one of them walked out with some kind of a prospekt that was filled with information. And that endured in a way that broadcasts from Voice of America or America Illustrated magazine didn't...The America Illustrated magazine - we printed it in hundreds of thousands, but most of them never actually made it into people’s hands. The Soviets would give them back to us as “unsold.” And we just know there is no way these were unsold. If you put them out, these would be gone; people would buy them in an instant. So, obviously, at the exhibit, you would give people this prospekt, and the prospekt just talked about America in a sort of counter-propagandizing way to what people were being told about America and the Soviet Union. But that was the whole idea. How do you calculate the effect of all of that?"

John Aldriedge served as a guide on the United States Information Agency’s (USIA’s) Hand Tools USA exhibit in 1966 and on the Education USA exhibit in 1970. He was a research officer for the Photography USA exhibit in 1976–1977. He was deputy director and, later, director of the Information USA (1987–1989) and Design USA (1989–1991) exhibits. He subsequently served at the Foreign Press Center in Washington and as a developer at Electronic Data Systems.

Gail Becker was involved in the exhibits program of USIA for 25 years. She started in 1965 as a Russian-speaking guide for Architecture USA. In 1991, she ended her service as chief of exhibits development and production at USIA to become executive director of the Louisville Science Center in Kentucky.

John Beyrle was a guide on the Photography USA exhibit in 1977, demonstrating Polaroid cameras to Soviet visitors. For the Agriculture USA exhibit (1978–1979), he oversaw transportation and set-up logistics in six Soviet cities. He served as the USIA escort officer for the 1979 Soviet Sport exhibition in the United States. He joined the U.S. State Department in 1983 and, during his 30-year career, served as Ambassador to Bulgaria (2005–2008) and Russia (2008–2012).

Thomas Bickerton served as a Russian-speaking guide for the Photography USA exhibit in 1977 and as an administrative assistant for the Agriculture USA exhibit in 1978-1979. He later coordinated the work of the U.S.-USSR Bilateral Technical Exchange Agreement on Housing as a consultant. In 1981, he joined the U.S. Department of Agriculture, serving as a Russian foreign affairs specialist, economist, and satellite and aerial remote sensing coordinator until his retirement in 2014.

Gerri Bickerton, who speaks Ukrainian, was hired in 1977 by the Photography USA exhibit to greet and present brochures and buttons to Soviet visitors, and to work on exhibit logistics in Ufa, Novosibirsk, and Moscow. After returning to the United States, she worked as a nurse until her retirement.

Kaara Ettesvold worked on the Photography USA exhibit in 1977 and on Agriculture USA in 1978 before joining the National Academy of Sciences' Section on the USSR and Eastern Europe. During a 33-year career in the Foreign Service, she spent twelve years in the USSR/Russian Federation.

Robert Houser was a photography specialist on the Photography USA exhibit (1976-1977) and worked in several Soviet cities. After earning a history degree from Boston College, he decided to pursue photography as his medium of expression. He views his photographs as documents that record, for history, the people he has met, the places he has been, and the things he has seen.

Michael Hurley served as a guide for the Outdoor Recreation Exhibit (1973-1974), the 1976 Bicentennial Exhibit, and the Photography USA Exhibit (1976-1977). In 1985, he joined USIA to begin a 30-year career with the U.S. Foreign Service. He went on to work with the Office of the Coordinator for East European Assistance on democracy issues and Bosnia. He has also been posted to Kuala Lumpur, Moscow (three times), Surabaya, and Budapest. In Russia, he raised $2 million in the private sector as the chief architect of a two-year celebration of U.S. culture. Hurley is currently a program officer at Meridian International Center.

Roland Merullo worked as a guide for the Photography USA exhibit in 1977. Between 1977 and 1987, he served in the Peace Corps in Micronesia and ran his own carpentry business in Vermont. He returned to USIA to serve as general services officer for the Information USA exhibit (1987-1988) and as field director of the Design USA exhibit (1989-1990). He has published six nonfiction books and 13 novels, including A Russian Requiem, which is based partly on his exhibit experiences.

Marguerite (Margot) Mininni was a guide for the Photography USA exhibit (1977) and a coordinator for the Information USA exhibit (1987–1988). She has worked in the business, non-profit, and governmental sectors, focusing on Russia and other countries in the region, for twenty years, including service at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. She has spent much of her career working on scientific engagement and nuclear nonproliferation, primarily at the U.S. Department of Energy/National Nuclear Security Administration.

Thomas Robertson was a guide for the Technology of the American Home exhibit (1975-1976), and was deputy director of the Photography USA exhibit (1976–1977) and the Agriculture USA exhibit (1978–1979). He later served as a foreign service officer with the U.S. State Department. He served at the U.S. embassy in Moscow from 1982 to 1984 and 1995 to 1997. He was director of Russian affairs at the National Security Council from 2001 to 2002 and the U.S. ambassador to Slovenia from 2004 to 2007.

Kathleen Rose served as a guide for the 1977 Photography USA exhibit. From 1974 to 1976, she worked for General Electric’s Center for Advanced Studies, known as TEMPO, as a researcher and analyst, focusing on economic and environmental issues in the United States and the USSR. From 1977 to 1987, she served as a part-time interpreter for various organizations that hosted Russian visitors to Washington D.C. She now runs a commercial organic farm in California with her husband.

Paul Smith served in several roles in four consecutive USIA exhibitions from 1973 to 1979. He retired in 2003 from a 30-year career in the U.S. Foreign Service, during which he served in St. Petersburg, Moscow, East Berlin, Warsaw, and Bonn. During his career, Paul specialized in the development and management of educational and youth exchange programs between the United States and Eurasia.

* * *

Izabella Tabarovsky is a Senior Program Associate at the Kennan Institute. She writes about the politics of historical memory in the post-Soviet space, the Holocaust in the Nazi-occupied Soviet Union, and Stalin’s repressions.

Cover photo courtesy of Paul Schoellhammer