Fall 2016

Cuba and America, the Next Generation

Their parents and grandparents fought Castro for half a century. Now these young Americans are helping bring United States-Cuba relations out of the Cold War’s long, dark shadow.

The slowly improving relationship between the United States and Cuba has begun to give Americans permission to travel to the island. But it also gives someone like me, an American-born Cuban (ABC, as we’re known) with roots on the island, a much more significant opportunity: the ability to ride the wave of that travel and tell the stories I need to tell — those of my family, my friends, and my fellow ABCs. These stories represent a people, a diaspora, and the long legs of a Cold War that divided families for decades, through belief systems that often made the mere 228 miles between Havana and Miami seem mythic.

I need to tell you the story of my grandfather, imprisoned for 15 years in Castro’s prisons. I need to tell you about a young man who brought his mother’s ashes back to Cuba, in the same instant at which Elian Gonzalez became the symbol of two ideologies tugging a long rope. I need to tell you about belly dancing in Havana and what that means to a young American woman trying to understand her mother’s Cuban body, her own roots, the undulations that sway beneath us all. These stories are important now, 25 years after the end of the Cold War, because it is only now that the war’s longest-lasting casualty — Cuba — is beginning to come into focus again for Americans. As we look to understand Cuba more deeply, it’s key to know how these stories helped bring the United States closer to Cuba once more.

Our first story begins in 1961, two years after Fidel Castro descends on Cuba from the Sierra Maestra Mountains and takes control of the island. The United States doesn’t like that. The US embassy in Havana closes its doors, and President John F. Kennedy attempts to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, but it’s a failed fiasco.

As the Soviet Union continues to ally itself with Cuba, Fidel declares: “I am a Marxist-Leninist and shall be one until the end of my life.” Across the Florida Straits, ripples start to reach the United States as the first wave of Cuban exiles flees for Miami.

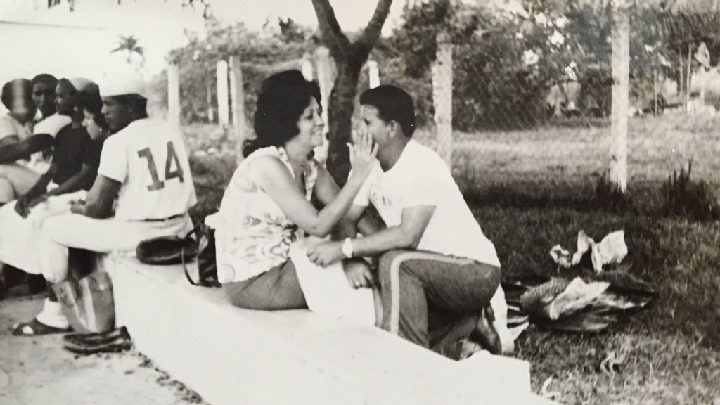

This is also the year my grandfather (my stepdad’s father) Armando met my grandmother Carmen. By 1961, Armando was already plotting against the Castro regime. Or, as he tells it, “fighting to get my country back from the Communists.”

As I write this, 55 years later, he is sick. He might even be dying, though the doctors won’t straight-out say so. He’s been sent home after his lungs tried to drown him. He has colon cancer, too, and has just undergone heart surgery. My abuelita Carmen warns him not to go outside. But he insists. It’s mango season in Miami, his tree is in full bloom, and Armando does not want to die. He wants to sink his teeth into fruit, live to tell his story. He is weak, though. I tell him I will help him get his words to you.

So, it’s 1961. Armando tells us he was working as a nurse in Cayo Largo del Sur, about 100 miles from Havana. On the afternoon he met my grandmother, his car had broken down. He was walking toward the mechanic with his friend Marianito when he caught sight of a trigueñita, a beautiful bronze-skinned brunette. Carmen was sitting on a ledge, her nose cute as button.

“Who is that?” Armando asked his friend.

“Calm down there, cowboy.”

Armando was a bit of a player, buzzing from flower to flower. At 34, his blue Sinatra eyes had been around the block a few times, so Marianito was worried. He knew the girl’s family and told Armando to stay away.

But Armando couldn’t. He was smitten. He moved fast. Less than a year later, Carmen and Armando were married. A year after that, Carlos, my stepdad, was born — a round turkey of a baby, weighing in at over 10 pounds. Armando, however, was not at the birth. He told Carmen he had to stay with a dying patient.

What Carmen didn’t know was that Armando had infiltrated the military hospital where he worked, picking up information about weapons, where they were, and where the Communists had them hidden, all information he passed on to counterrevolutionaries and, possibly, to the CIA. He also stole supplies from the hospital — syringes, gauze, antiseptic washes — to aid counterrevolutionaries who were injured. He even moved weapons himself from one place to another when necessary.

All of this caught up to him on the night of May 20, 1964. The night they took him away. He was on his way to work. At a red light, three cars surrounded him — Fidel’s militia — with bayonets in hand. It all happened so quickly, my grandfather didn’t even have time to reach for the pistol he kept on him. The guards ran up to his vehicle and hit him on the head with a rifle while he was still in his car.

That very night, they took Armando out, tied him up, head covered. He didn’t know where he was going, he just knew it was dark, and that there was bush all around. The guards taunted: You gonna talk? You have a young wife, and you have a son. You want your son to be an orphan?

At one point, one of the guards told the other to point the rifle at Armando. “Prepare,” Armando heard a voice call out behind him. He looked up, and it was so strange, the sky was so blue and starry, there was a new moon, and it was as if his life had become a film. Inside him, a surge of faith, for God, for things bigger than himself. It was just as people say it is, those moments before death — his life, rolling before him, from the time he was a kid until now. Then the guard’s voice jolting him from his reel: “Point ….” And then Armando lost consciousness.

But he didn’t die.

For the next 15 years, Armando was moved from prison to prison. He went from Combinado del Este to La Cabaña to Isla de Pinos.

Meanwhile, his son, Carlos, my stepfather, was growing up without him.

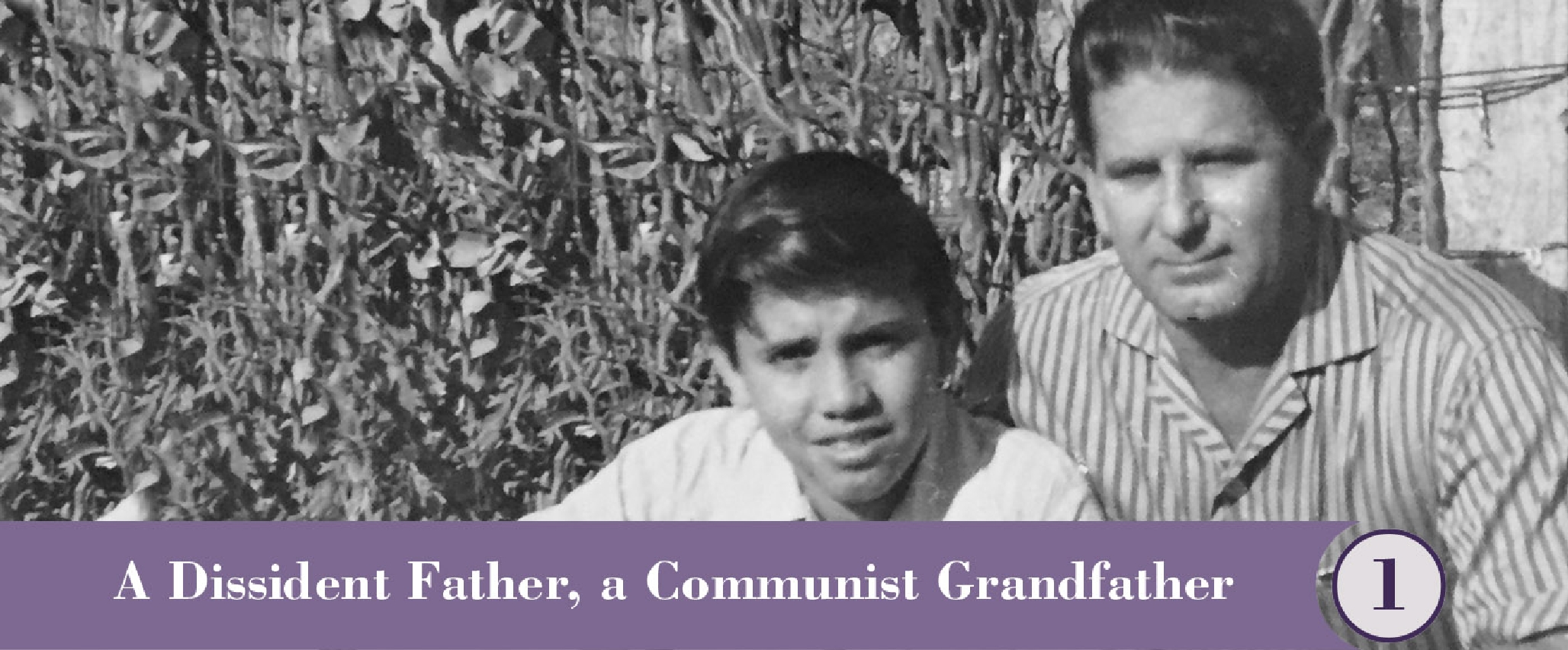

Carlos’ closest relationship was with his grandfather, Carmen’s father, who was a Communist sympathizer. Every evening, little Carlos — Carlito, as they called him — would stand by the door of the bathroom to watch his grandfather shave. Carlito would talk about his day, about the taunts he had to bear because his father was in prison, from schoolchildren, teachers, and neighbors alike. Carlos’ grandfather did not speak poorly of Armando. The only thing his grandfather would say every once in a while was: “Your father made a mistake.”

When Carlito visited his father in prison, Armando would tell him about a place not too far away called the United States, where people could say and do what they pleased. At school and home, the United States was a monster to the north, to be feared. At night, Carlito studied by candlelight, all of these ideas swimming in his head. Who was right, who was wrong? He didn’t know. But he was about to form an opinion of his own because as fate would have it, he would make it to the United States himself.

In their book, Back Channel to Cuba, William M. LeoGrande and Peter Kornblu detail US president Jimmy Carter’s negotiations with Cuba. Early in his administration, Carter issued a presidential directive stating that the United States should give normalization with Cuba a shot, and as part of negotiations he made the release of political prisoners like Armando a priority.

Carter didn’t achieve normalization, but by 1978, Armando was notified that he would be released from prison. Armando was told he could take his wife to the States with him but not his son. According to Cuba, Carlito was a “son of the revolution.”

At his aunt’s house, Carlos, now 16, was silent and heartbroken. He was reunited with a father he hardly knew, asked to leave behind his country and lie to the grandfather who raised him. He knew, however, that if he told his grandfather the truth, he would put his family’s escape in peril, and he couldn’t do that to a man who had spent the last 15 years of his life in a cell. So he closed his eyes, found temporary solace in his aunt’s library, and fled when the time came.

The Miami that Armando, Carmen, and Carlos entered was already a land of exiles, one other Cubans had sown and begun to grow into. According to Guillermo Grenier, sociology professor and Cuba expert at Florida International University (FIU), Cubans walked into an environment in the ’60s that was inspired by the Cold War, which shaped the discussion of Cubans in Miami. “The embargo, the Cuban Adjustment Act [which allowed any Cuban paroled into the United States to gain permanent residence after one year], all these things were established in an environment that the Cold War made possible,” says Grenier.

In other words, these were people fleeing the United States’ enemy, Communism, so the United States had to and wanted to welcome them. “It’s hard to imagine this in our current toxic [immigration] environment,” says Grenier. But it was what allowed Carlos and his family to make a life in the United States.

Carlos never saw his grandfather again. And for over 35 years, he has not stepped foot on Cuban soil.

Our second story begins in October 1998, the year Pope John Paul II visited Cuba and openly called for freedom of expression and association. It was the first papal visit to the island ever. The ’90s had been tough on Cuba, a “Special Period,” as Fidel called it. As a result of the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba, which had been heavily subsidized by the monolith to the east, was suddenly adrift in scarcity and hunger.

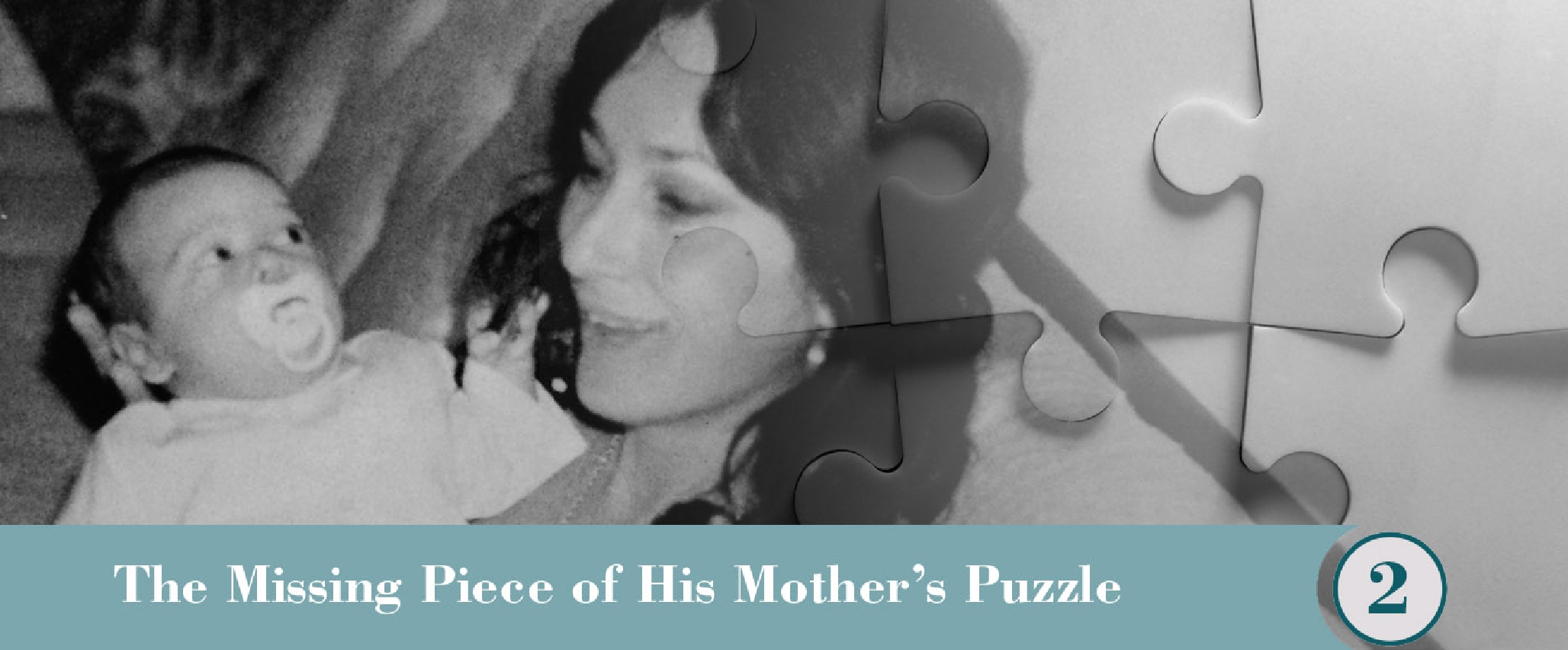

The Pope’s visit showed that despite the regime’s attempts to stifle religion, Catholicism had survived, and the crowds that met the Pope were proof. This was also the year my fellow ABC Joshua Paolino, a filmmaker and educator, received a spiritual directive of his own from his Cuban mother. On her deathbed, Josh’s mother told him: “I want to go home again.” Specifically, she wanted to be cremated, her ashes taken to her homeland, which she hadn’t seen in 38 years.

Her name was Maria Gonzalez, but everybody called her Lupita. She’d been the youngest child in her family in 1960, when, a week before her 22nd birthday, her family helped send her away to Miami. Lupita’s father thought Castro’s “revolution” would be just another blip in Cuba’s larger political landscape; the United States could never allow an island so nearby to fall to Communism. And so Lupita went to Miami, where she could improve her English and get along for a while with the money her father had given her to ride out the storm they thought Fidel would be.

Soon, however, Lupita ran out of cash and luck. In Miami, landlords turned her away: “No Cubans,” they’d said. Even if, as Grenier explained, the larger idea in the United States was to welcome the Cubans, life on the ground was not as swift. Lupita found herself sleeping in Bayfront Park, alone and afraid in a new city. Until she found work and started to make a life.

Ten months turned into 10 years. She kept in touch with her family back home, family that was now “stuck” in Cuba, and she made her way up the economic ladder in the States, for the most part, alone. Around the time she turned 30, she moved to Los Angeles in search of something new. It was there that she gave birth to Josh. His dad disappeared before Josh ever knew him, but Lupita would find a mate in an Italian-American man named Charles Paolino, who would legally adopt Josh.

In L.A., Lupita wanted to make sure her son knew about his Cuban roots. She taught him Spanish, and, together, they read the letters that came from family in Cuba, which sometimes arrived years after they’d been written. Josh’s mother would take him to Echo Park and show him the bust of José Martí, the national hero of Cuba, who had fought to liberate the island from the Spanish. On his own, Josh took to reading about the island too, taking in books about other patriots. When Josh was in high school, things started to change. During a short period of time in Reno, Nevada, where they had moved for a while because of Charles’ work, he had a teacher who, referring to Josh’s perfect Spanish, told him: “We don’t speak that here.” That phrase did something to him, and he stopped speaking Spanish. When his mother talked to him, he responded in English.

Still, his mother tried to keep the ties to Cuba as tight as she could. When it came time to order yearbook pictures, she always ordered an extra set to send back to Manzanillo, where most of her family still lived.

Some nights, Josh would walk into the kitchen and see his mother at her jigsaw puzzle — she loved putting puzzles together; it was her thing, her pastime. Sometimes, he would catch her crying by herself, trying to put the pieces before her together. Josh could never understand why she was crying, and his mother didn’t know how to explain.

Eventually, Josh came back to Spanish, and, after his mother died in 1998, he decided to move to Miami for film school. He drove across the country, with his mother’s ashes in the front seat. “It was as if she was riding back to Miami with me,” said Josh. He’d made sure that THESE ARE HUMAN REMAINS was stamped in big letters on the box. He knew that, eventually, he would have to be true to his promise and take his mother back to Cuba. “I knew that I would have to go into a repressive Stalinist regime,” said Josh, “and I was worried that … I had visions in my head that they would try and open the box, that I would fight them and I would go to jail that day over fighting someone for a box of ashes.”

When Josh finally arrived in Miami, in 1999, less than a year after his mother’s death, the city was about to be engulfed in the Elian crisis.

Elian Gonzalez was a five-year-old Cuban boy who managed to become a symbol. Elian’s troubles started when his mother and her boyfriend decided that they needed to escape Cuba by any means possible. They jumped on a raft and fled. The Elian debacle was a trickle-down effect of the Cold War. The starvation and desperation of the Special Period forced Cubans to flee, daring even the sea. As a result, the Cuban Rafter Crisis hit Miami. During the first two weeks of July 1994, 500 rafters arrived daily. In response, the United States created the “wet foot, dry foot” policy, a revision to the Cuban Adjustment Act that dictated that Cubans coming into the States had to touch dry land to be paroled. They would no longer be accepted into the country if found at sea.

Like so many other rafters, or balseros, Elian’s mother lost her life at sea. The boy, however, survived. Fishermen and the Coast Guard found Elian right off the coast of Fort Lauderdale. Miami relatives claimed him, but Cuba also claimed him, with his father, and the regime insisting he be sent back. What ensued was a tug of war between two ideologies that ended in a brutal scene when armed federal agents took the boy, by force, and sent him back to his father on the island.

Josh didn’t quite know what to make of the situation. To a certain degree, both Elian and Josh were motherless and adrift in Miami. The only thing Josh knew for sure was that he was going to take his mother back to Cuba during winter break from film school. He knew it would be difficult for him to do this. His mother had never, in life, wanted to return to the island as long as Castro was in power. Like many exiles, she feared the sight of Cuba’s deterioration and did not want to feed the regime that she believed caused that deterioration. Yet Lupita had given her son a directive in death, which he now had to follow.

In the late ’90s, President Bill Clinton, partially in response to Pope John Paul II’s call to improve United States–Cuba relations, began to loosen the knot of restrictions that had been pulled tighter earlier in the decade. Cuban-Americans were freer now to visit family, uncover their roots.

That’s how, in January 2000, at the turn of the new millennium, Josh found himself at his family’s house in Manzanillo. When his uncles and cousins opened the door, he looked around and saw pictures of him and his mother everywhere. All those bad yearbook pictures, year after year, awkward phase after awkward phase — they were plastered all over the apartment. This hit him hard, and he broke down. He started to cry, like his mother had cried over her puzzles. He’d never liked puzzles, but now he realized he was putting together the pieces of his life and his mother’s. When his little 12-year-old cousin asked him what was wrong, why he was crying so much, he told her: “I finally understand my mother, after all these years, I finally understand.”

All her siblings, nephews and nieces — people Lupita and Josh could reach only through letters — there they were. Josh felt as if someone had pressed a pause button on Cuba, and now he was seeing what he hadn’t seen for all those years, what his mother wasn’t ever able to return to.

The next day, Josh walked into the water and scattered his mother’s ashes in the sea, off the coast of Manzanillo. He felt an enormous relief, a sense of peace. An understanding that mother and motherland had become one.

Our third story begins in 1980, the year of the Mariel boatlift, when thousands of Cubans flooded the Peruvian embassy, seeking asylum. Fidel, prompted by this act, allowed anyone who wanted to leave Cuba to find their way to the port of Mariel, west of Havana. If they could find a boat to leave on, they could go. Exiles in Miami quickly took up the call and picked up family, and sometimes strangers, at Mariel and brought them back to the States. Fidel also opened up the jails and released prisoners. Soon 125,000 Cubans had reached South Florida.

Several months before the Mariel floodgates opened, Tiffany Madera was eight years old and about to see Cuba for the first time. Both her parents were Cuban émigrés in Miami who, in 1980, decided to go back to Cuba to visit family they hadn’t seen in many years. In 1979, Cuba had, for the first time, allowed exiles to come back to visit the island, and Tiffany’s father wanted to see his mother and sister again. Tiffany’s mother, Maggie, agreed that this trip was important, despite the fact that her own father, Dr. Denio Fonseca, was a hardline Cuban-American radio show host and physician in Miami who aligned himself with the idea that you did not return to Cuba until Castro was out of power or dead. Maggie kept the trip secret from her father.

For Tiffany, arriving at the José Martí Airport was like a movie. Everything was above her eye level, but she felt the vibrations of something she’d never felt before, and it got its hooks in her. The doors of the airport opened onto Havana, and swarms of people were gathered. Entire families and groups of friends, waiting for stories of the outside world, waiting to see a mother, sister, brother they hadn’t seen in years, waiting for goods from abroad — ibuprofen, eyeglasses, toilet paper.

In the pulsing crowd was her family, people she had never met. They rushed toward Tiffany, her brother, and her parents. Her dad’s sister and mother were grabbing onto her own mother, who was crying. Tiffany watched as her parents lost their customary composure and crumbled in the arms of a crumbling city. At the time, Tiffany didn’t have words for what she was experiencing. Later, after a graduate degree in Latin American and Caribbean studies from FIU and an MA in performance studies from New York University Tisch School of the Arts, she would analyze it. “I didn’t understand it then, but what was happening was that I was losing my mom and meeting her for the first time, seeing her in her most true identity, as a Cuban woman,” says Tiffany now, at 43. Just as Josh had met with a core understanding of his own mother when the doors of his family home opened up to him in Manzanillo, so had Tiffany at the José Martí Airport.

Maggie, Tiffany’s mother, unlike Lupita, had stayed behind in Cuba while her family escaped through the embassy of Costa Rica back in late 1959 or early 1960. Maggie’s father, an ardent anti-Communist, was convinced, like Josh’s grandparents, that the revolution would end quickly, so they left Maggie behind to take care of property. They planned to rejoin Maggie in just two weeks’ time. As it turned out, Maggie got stuck in Havana, just as Lupita’s family had.

One day, a member of Castro’s militia knocked on the door of the family’s Havana apartment, not long after Maggie’s family had left. He let himself in and told Maggie that she had a choice: “Either we are intimate, and you keep your furniture, or we are not intimate, and we take it all.” Maggie could not bear the idea of having sex with this man. A few hours later, she found herself on the floor of her apartment, without furniture, cross-legged and diminished. It took another year before her parents, from abroad, were able to help Maggie escape through Mexico. In Mexico, she lived in a refugee home, sacks of flour on the floor, worms making their way out of the sacks. Worms, gusanos, which is what Castro called Cubans who left the island.

Tiffany couldn’t possibly know about all of this history at age eight, but she felt it. On that first visit, they went to Pinar del Rio, where her family was from, and she immediately acclimated to almost everything except for the fact that she missed her feather pillows. Tiffany played with the kids in the street and wanted to look like them. They all wore pionero school uniforms — a white shirt, red bandana around the neck, and a red jumper dress, just like the Soviet “pioneer” schoolchildren. Tiffany wanted one more than anything.

By the end of the trip, Tiffany had managed to get her hands on one and wore it on the airplane back to Miami. Maggie didn’t want any of her close friends to see her daughter in such an outfit. It would have caused a stir.

It was Tiffany, many years later, who would break completely from the hardline and work to tear down the wall between her body and Cuba’s. In 1998, the year the Pope went to Cuba, the year Josh’s mother was dying, Tiffany went back to connect with a long-lost uncle and to study dance. She was a guest of the Conjunto Folklorico, the National Folkloric Company of Cuba, where she took lessons in Afro-Cuban and Orisha dance. She went to the homes of professional dancers and learned to move, sometimes without music because there was no electricity, no boomboxes, just the sound of claves — two wooden sticks, keeping rhythm. The homes were crowded, several generations under one roof. Some of her instructors’ family members slept on the couch as Tiffany began to take Cuba in a little deeper, trying to understand her own body and her mother’s.

In 2003, it was time for her to give back, and she did that by bringing belly dancing to Cuba. By then, she’d become a professional belly dancer, and while visiting a hip-hop festival in Havana, she connected with a group of Cuban women who wanted to learn the art of Arabic dance. One of these women was named Gretel S. Llabre.

Gretel invited Tiffany to teach the women lessons from her home in Havana. Immediately, the two women forged a bond that stands to this day. They made what they both refer to as a spiritual pact. Tiffany returned to Miami, but soon she was raising funds to head back to Cuba so that she could bring more belly-dancing lessons and supplies to her cohort. She returned dozens of times, and eventually Gretel opened her own dance school in Cuba.

Meanwhile Tiffany discovered that what she was doing, in part, by dancing in Cuba was connecting with her mother, or “dancing her mother’s body.” By then, she’d learned about her mother’s near-rape, at 17, and connected it to her own. Tiffany had, herself, been raped in New York City as a young woman. Their pain, that of mother and daughter, played and replayed in the undulations of Tiffany’s belly, her womb giving birth to her mother, just as her mother had given birth to her — all on the island that both divided them and brought them together.

The island, it turned out, had and still has a great deal to teach each of us. It taught Josh that his stance on Cuba was perhaps too harsh. After his trip, he started to question the US embargo on his island and his people. “My whole perspective on the embargo and US-Cuba relations really changed after that trip; when it’s personal, when you see how the poverty affects people that you are connected to, it just changes the whole situation,” he says. Josh still thinks the regime in Cuba is a repressive one, but he also believes that reconnecting with the island is essential. He hopes to return to Cuba next year and possibly document the story of his family.

As for myself, I have now gone to Cuba twice and am planning a third trip early next year. The first time, I went with my mother, and it is because of this trip — and the decades it took to get there — that I understand Josh and Tiffany and so very many other ABCs.

When I landed in Havana with my mother back in 2014, she hadn’t seen Cuba in 53 years. She had been reticent to return. In fact, it took me 15 years, the same number of years Armando was imprisoned, to convince my mother to return. Like Josh’s mother, she didn’t want to give tourist money to the regime that had ousted her from her homeland. She also feared Cuba.

The day I convinced my mother to go back to the island with me was one of the most memorable days of my life. That was the day I broke what I call the Familial Embargo — the embargo imposed by exile families that, given the circumstances recounted in this essay, is easy to understand but that only served to further isolate the island we were from, an island that deserved then, as it does now, to be a part of the world.

The ties that tugged at our hearts the day my mother and I landed in Havana take a book to describe — a manuscript I have just completed and that I hope will find its way to the world, just as Cuba reconnects with the United States.

I am not the only one who feels the impulse to record at this moment in history. Tiffany recorded her journey back to Cuba in the just-completed documentary Havana Habibi, which made its Miami debut this summer and will premiere in Havana in December.

The one thread of Tiffany’s story that remained outside the tapestry she was carefully unwinding and weaving back together was her grandfather. Denio refused to accept the trips Tiffany was taking to Cuba and, as a result, they did not speak for years. Denio died in 2014, without ever fully repairing the relationship with his granddaughter.

“It will take generations,” says Maggie today, at 70, for the Cuban diaspora to find peace and heal. “I don’t think it will happen in my lifetime.” Maggie is afraid for her daughter each time she returns to Cuba. For her, like my mother, Cuba is not a safe space. But she is also proud of her daughter and of what she has made.

The famous Cuban songstress Celia Cruz used to sing a song called “Por Si Acaso No Regreso” (“Just in Case I Don’t Return”). In the lyrics, Cruz sings about Cuba, and she tells the land not to suffer, not to lose heart because there is no hardship that can last 100 years, no hardship that a body can withstand for so long.

I think of this song today, as I come to the end of this piece. Because of all my fellow ABCs and their families, their stories. But also because yesterday my own grandfather, Armando, died. He was home, staring at his mango tree, when he fell to the ground. A friend had brought him the seed of that tree from Cuba, and it had bloomed in his backyard, canopying the yard with rich fruit. As he stared at the tree, his aorta burst and he collapsed. His wife, Carmen, went to his aid. But it was too late. His body had had enough. In Celia’s song, the lyrics continue:

Si acaso no regreso … me matará el dolor… Si no regreso a esa tierra, me duele el Corazón.

If per chance I can’t return … the pain will kill me … If I can’t return to that land, my heart will hurt.

The song also says that soon the time will come when suffering will be erased and we will put away our rancor, share in one same sentiment.

It is my journey, as the child and grandchild of those who never saw their homeland again, to work toward unity, never forgetting those who came before. I believe it is so for many of us ABCs, who bring our parents back to the island, if not in body then in ash, if not physically then within us and in spirit. Just as the younger generations took to the streets in 1989 to tear down Berlin’s wall, so have we been chipping away at an invisible wall, much more slippery, much trickier to tear down.

* * *

Vanessa Garcia is the author of White Light, a novel named one of NPR’s Best Books of 2015. Follow her on Twitter @vanessathekrane.

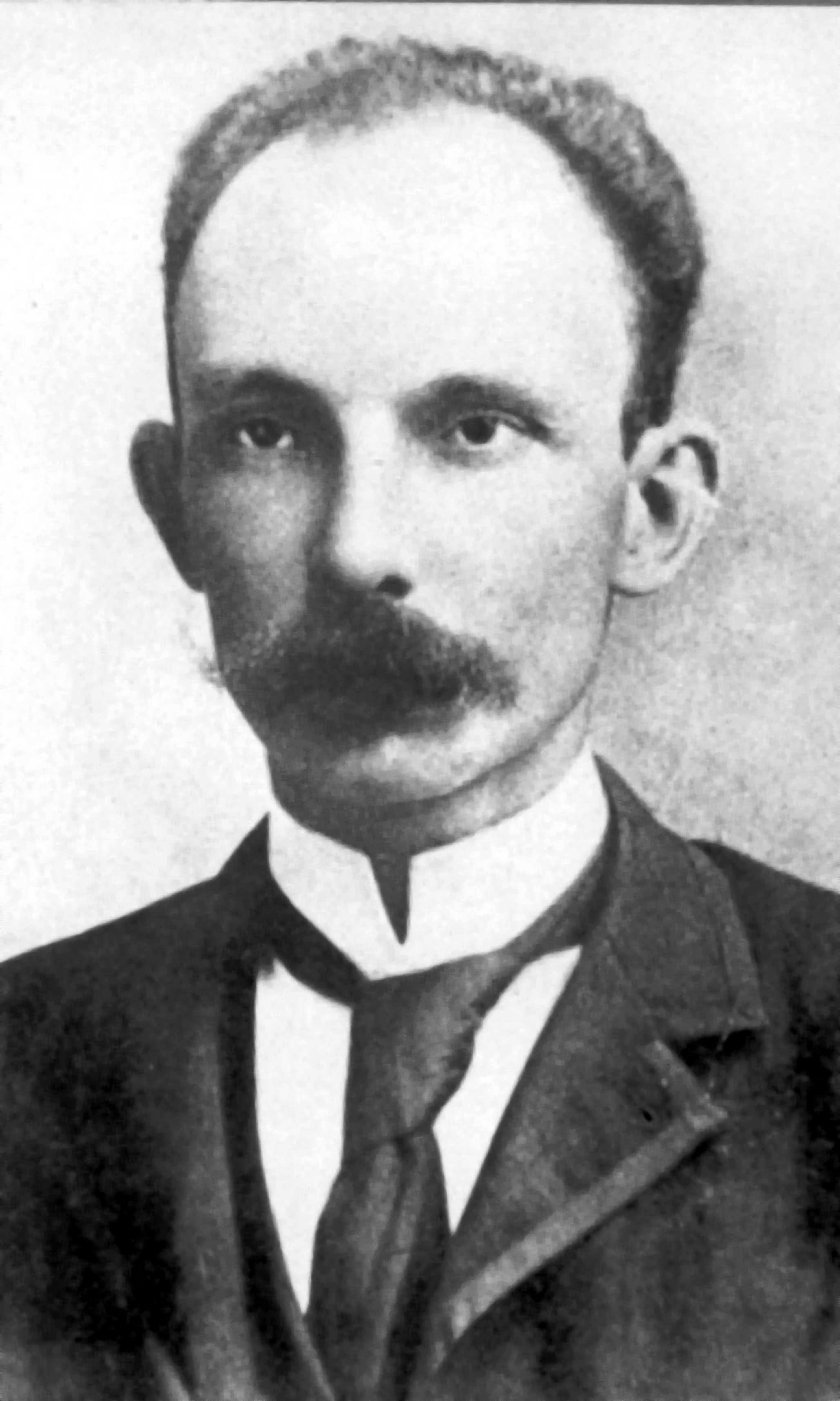

Cover photo courtesy of Carlos Diaz-Sampo