Fall 2015

Coming to America and Coming of Age

– Asthaa Chaturvedi and Jenny Luna

Nelson escaped gang violence in Honduras and crossed the border illegally. The 19-year-old now faces a new country, high school, and immigration court, while New York City grapples with the legal proceedings of the thousands of unaccompanied Central American immigrant youths like him.

Nelson’s day begins at midnight. He washes, dries, and folds linen for local restaurants until 6 a.m. An hour later, the 19-year-old reports to class. He is about to enter tenth grade. He lives on his own in a boarding house in Lindenhurst, Long Island, and is one of thousands of recent immigrants who crossed the border as unaccompanied minors and settled in the New York area.

Nelson, a slim boy with his hair spiked up with gel, looks down at the floor when he talks about his journey to the border. He had grown up in Honduras, near Colón, where his parents worked on a coffee farm. Nelson began working alongside them at the age of 10. He did not go to school, even though he wanted to. And local gangs saw him as a prospective recruit, even while they extorted his family.

“They said they would kill my family,” he says. “We couldn’t live peacefully.”

In the summer of 2013, Nelson left Honduras for the United States. He was 17 years old and on his own. By the time he arrived in America in June 2014, a flood of unaccompanied minors was already following in his footsteps.

While policymakers were taken by surprise, advocates and those who work in the immigration field say that they saw this rise coming. In Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, gang and drug cartel violence have reached unprecedented heights. Honduras, for one, has the world’s highest murder rate. And according to the UN Office of Drugs and Crime, “the homicide rate for male victims aged 15-29 in South America and Central America is more than four times the global average rate for that age group.”

According to U.S. Customs & Border Patrol, nearly 60,000 unaccompanied migrant children were apprehended along the U.S.-Mexico border between October 2013 and September 2014 — almost double the number apprehended during the previous fiscal year. From October 2014 through July 2015, as detention centers continued to overflow and courts struggled to keep up, more than 17,000 unaccompanied, undocumented minors were released to sponsors across the country.

Today, thousands of these children are waiting to learn whether they’ll be granted immigration papers to stay in the United States.

On This Side

Nelson’s family knew he was going to leave. At 4 a.m. on March 2, 2013, he and a friend from his neighborhood — neither of whom had left their hometown alone before — waved goodbye from a bus that would pass through Guatemala to Mexico. At a safe house for immigrants in the southern state of Chiapas, Nelson was given a paper map to help him learn the route. Over the course of nearly three months, Nelson traveled 1,300 miles through Mexico, riding on the roof of a freight train known by travelers as “La Bestia” — the beast.

“I had to hold onto something on the train so I wouldn’t fall because it was so shaky and cold,” Nelson remembers. “I think I avoided dying of cold and, maybe, hunger.” Nelson and his friend were not alone on La Bestia: the teenagers rode alongside people who were escaping crime or were themselves fugitive gang members. In their third week in Mexico, Nelson’s friend got off the train as it stopped at a station. Nelson stayed on and, before he knew it, the train was moving — leaving his friend behind.

Every day during his journey, Nelson would get off the train to beg door-to-door for food from the homes near the railroad tracks. Many days, he could only manage to scrounge up some bread and water. On other days, he didn’t eat at all.

“It’s just that I don’t like to remember much from those days,” he says, “because it brings back so many bad memories of how I lived and survived to come here.”

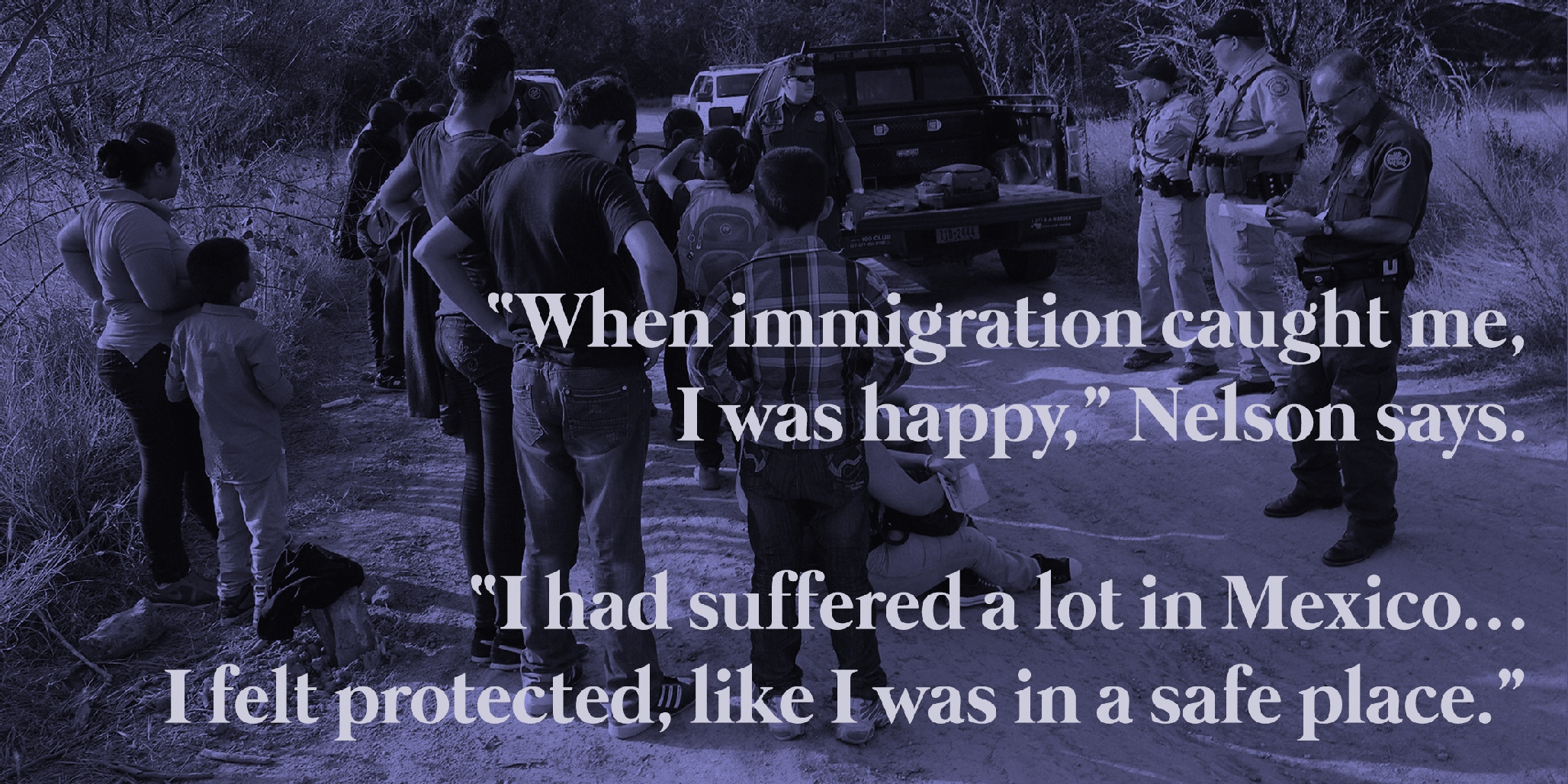

The night Nelson finally arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border, he and other immigrants crossed the Rio Grande in an inflatable raft. Within an hour, immigration authorities patrolling the border caught Nelson and took him into custody. After such a long journey, the kids were elated. “When immigration caught me, I was happy,” Nelson says. “I had suffered a lot in Mexico and with U.S. immigration I felt protected, like I was in a safe place. I felt like nothing would happen to me.”

Nelson spent three months in a detention center in Harlingen, Texas, waiting for immigration officials to approve his cousin Carlos, who lived in New York, as a sponsor. He says that officials provided him with clothing and food. Nelson took classes as well. Officials from the Office of Refugee Resettlement informed him that he would have to enroll in school once he arrived in New York.

Carlos picked Nelson up at the airport in September. Carlos is in his early thirties and came to the United States illegally 12 years ago. They shared a heatless room in Lindenhurst for two months, until Carlos told Nelson that he was leaving to work in Miami. The teenager was once again on his own, and found work in a commercial laundry to pay his monthly $320 in rent as well as his food bill. Nelson speculates that Carlos left because he could not find work in New York, or perhaps because he preferred the warmer weather in Florida or possibly feared deportation. Nelson was already on the radar of immigration authorities, with an appointment scheduled but several months away.

Since July 2014, unaccompanied migrant children who come illegally from Central American countries must appear in court within 21 days of receiving notice. That mandate, paired with the surge of young immigrants, put a burden on immigration courts and lawyers. Attorneys at legal aid organizations in New York like The Door, Catholic Charities, the New York chapter of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, and the Safe Passage Project went from seeing 15 children per month to 30 per day.

In the same courtroom where Nelson was directed to go that May, volunteers and lawyers continue to spend at least one hour with those who arrive for the first time after receiving a court date. During the “intake,” as lawyers call it, Nelson met with lawyers from the Safe Passage Project, a nonprofit immigration law organization within New York Law School, and they took on his case. “We do in-depth screenings to find out how we can best serve the kids — to find out all the possible avenues of relief,” says Guillermo Stampur, supervising attorney for Nelson’s case. “There are a number, and we just want to make sure that we hit all of them.”

For immigrant minors, having legal representation during the hearings can mean the difference between deportation and staying in the United States. According to a November 2014 report by Syracuse University, three-quarters of those with counsel were able to secure some form of immigration relief. Of those children who did not have an attorney, only 15 percent are allowed to stay. Attorneys represent only one-third of pending cases involving unaccompanied juveniles. There are over 2,000 pending cases in New York City.

Guillermo Stampur, Nelson’s supervising attorney, speaks Spanish and shares Nelson’s love for soccer. During court proceedings earlier this year, Stampur guided Nelson in seeking Special Immigrant Juvenile status, a designation for unmarried individuals under the age of 21 whom the court determines have legitimately left their home countries due to severe abuse, neglect, or abandonment. The process of applying for Special Immigrant Juvenile status takes a year, Stampur says, involving approvals by family court and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

If approved for Special Immigrant Juvenile status, Nelson will be eligible for a green card and eventually for U.S. citizenship. He does want to be able to visit his family, however. “I have hope that maybe one I can go to visit them and see them. I could go for a week,” he muses, “and then come back here.”

Fighting to Learn

Nelson started school more than a year after his arrival in New York. The would-be student went on his own to Lindenhurst Senior High School administrative offices three times. Each time, he was turned away or was given an enrollment form in English. He did not receive any help enrolling until Safe Passage stepped in.

Astrid Avedissian, a Safe Passage AmeriCorps fellow, worked on Nelson’s school enrollment. “We researched a federal law called McKinney-Vento which forces schools to make special exceptions for children that are considered homeless, or homeless eligible,” Avedissian says. “[Nelson’s] a subtenant. He lives with strangers. He occupies a tiny space in the basement of a house where he has no relatives and he could be thrown out at any moment. And he has absolutely no safety net.”

The school refused to budge. Avedissian eventually reached out to a contact in the New York State Department of Education, and the New York Attorney General’s office called the Lindenhurst school district to get Nelson enrolled. “They said we’re calling for a specific child,” she says.

Avedissian brought down the number of required documents for Nelson’s enrollment from at least 10 to two, she estimates. When the school asked for the name of an emergency contact, Nelson asked Avedissian to list her contact information. Nelson couldn’t understand the words exchanged between the woman in the office and Avedissian, but he grasped the meaning. Tense words turned to smiles and the enrollment office accepted the two documents he did have.

On the way home, the shy boy sat in the passenger seat of Avedissian’s car, dialed Stampur’s number, and handed her the phone. She handed it back to him.

“It’s your news, you tell him,” Avedissian told Nelson. Stampur was in a meeting with other Safe Passage employees. He put Nelson on speakerphone.

“We’re all here,” Stampur said. “Tell us your news.”

“Gracias a ustedes,” Nelson began. “Thanks to all of you and your hard work, I am enrolled in school,” he said. He began to cry. Tears streamed down Avedissian’s face, too.

“It felt like my biggest little win,” she said a few days later.

After taking a placement test, Nelson was registered for ninth grade. English is still a struggle for him, but after two years he is able to understand more of it. His favorite subjects are math and English. “I like mathematics because I understand it better. It’s less words, more numbers,” he says.

Nelson’s enrollment ordeal was not unique. Recent reports have shown that certain schools in counties around New York City are not completing obligations to enroll and place new immigrant students into classrooms as outlined by the Department of Education. In February 2015, following reviews showing serious transgressions when students tried to register, the state department of education, the New York Attorney General, and 20 school districts came to an agreement to remove any barriers for unaccompanied minors and undocumented students.

Sacred Soccer

Right now, with the wages he makes, Nelson is not saving any money to send back to Honduras. The commercial laundry where he works pays him in cash, and he pays for his rent, school necessities, and food. He lives in the same sublet room in the boarding house his cousin lived in earlier. The other people he lives with are immigrants who arrived in the United States years ago, and although none of them is Honduran they are all from parts of Central America, where soccer is a staple.

He lives with strangers in a tiny space in a basement he could be thrown out at any moment. He has absolutely no safety net.

Nelson travels almost two hours from Long Island to come to Safe Passage events in Manhattan. Even in last winter’s persistent cold, he traveled many Saturdays in a row to meet up with the volunteers and attorneys for pick-up soccer games. One particularly rainy day on the soccer field, Nelson met Bryan, an 18-year-old from Guatemala, who also asked to be referred to by only his first name. The boys shared more than their love for the sport: both had ridden La Bestia, had left families at home, were acclimating to new high schools, and were working minimum-wage jobs to get by.

But the stress of their realities faded while they ran on the soggy green field at Mullaly Park in the Bronx. The boys threw out high-fives and teased one another by calling each other “Messi,” “Ronaldo,” and “Suárez” — the names of their favorite soccer stars. Stampur played with them.

“I love soccer,” Nelson says. “When I play, I’m not thinking about anything else.”

The kids call the games “soccer Saturdays.” In March 2014, Catholic Charities Immigration and Refugee Services teamed up with South Bronx United, an organization that encourages youth development and leadership through soccer, to offer weekly pick-up matches for kids with shared experiences of crossing the border alone. Elvis Garcia Callejas, a case manager with Catholic Charities, organized the games and said that most of the kids haven’t missed a day on the field since they started playing in March.

“It helps create a sense of community,” Garcia Callejas says. “They understand each other and it gives them a sense of belonging.”

The cold continued and the rain didn’t stop. Nelson and Bryan ran hard to keep up with Stampur; his agility surprised them. The teenagers knew Stampur only in his suit and tie, with white folders covered in Post-its under his arm. But on the waterlogged field, the wild-haired lawyer wore a raggedy blue sweatshirt and Adidas sweats. He had fancy footwork, and landed some terrific shots. The former co-captain of Columbia University’s soccer team and coach of a Manhattan Soccer Club team, Stampur likes to earn his clients’ trust on the pitch.

After three hours of playing in the rain, Nelson, Bryan, and Stampur returned to the sidelines to gather their things. They scarfed down the bagels that Safe Passage volunteers had brought that morning. Bryan turned to Stampur, panting and gleaming with sweat. “Gui, this made me feel like a kid again,” he said. “Running around in the cold rain, not even knowing it was cold and rainy.”

Stampur wrapped his arm around Bryan and asked a Safe Passage volunteer to take their photo. “You’re still a kid, hermano,” Stampur told him. “You’re only 18. This makes me feel like a kid again, too."

Bryan arrived in July 2013. Like Nelson, he chose to travel across Mexico and leave behind seven siblings; his parents could not afford to send him to school or pay for basic necessities like food and clothing. He now lives with his uncle and two cousins in Brooklyn and attends high school in downtown Manhattan. Bryan, like Nelson, had to wait over a year to enroll because of documentation requirements that he was unable to meet.

Stampur presented the kids with an old trophy he’d brought for fun. Myriam Santa Maria, a small 19-year-old woman and an intern with Safe Passage Project, framed the group with her camera.

“Say ‘cheese,’” she said. “Or, dice ‘queso.’” Santa Maria remembered everyone calling out their own sayings that meant to smile for a picture.

“Que-so!” the teenagers said in unison, with their biggest smiles.

“Now a photo jumping,” Stampur said in Spanish. He counted down from three, and Santa Maria attempted to capture the one-day soccer stars mid-jump, but laughed out loud, missing the shot.

Though they continue to cross the border in hopes of a better life, the rate of children coming to the United States has decreased since the summer of 2014.

Maureen Meyer of the Washington Office on Latin America, an advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C., estimates that even though numbers will not be as high as they were a summer ago, tens of thousands of migrant children from the Northern Triangle of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala will still cross the border. This February, President Obama requested a $1 billion package to bolster security in the Triangle. Mexican authorities have also started apprehending more children, relieving the overworked U.S. Border Patrol.

After graduating, Nelson wants to be a police officer. “I like justice,” he says.

Nelson talks to his family once a week by phone. He writes in a notebook, little by little every week, recounting his journey. In a story titled “El joven immigrante,” he has drawn images and writes in more detail about leaving Honduras.

It’s hard to measure the number of individuals and organization that support the unaccompanied minor migrant, New York’s newest group of immigrants. Whatever decisions Congress and immigration officials make, young men and women will continue to ride La Bestia, hoping to find solace on the other side of “la frontera,” the frontier, in the most desperate of situations.

After finishing high school, Nelson says that he wants to be a police officer. He smiled bashfully when he explained why. “Because I like justice. I might also want to be a — how do you say it — pilot. But it’s a while until I get there. I know I have a long way to go.”

* * *

Asthaa Chaturvedi (@Pasthaaa) is a journalist. She most recently worked with FiveThirtyEight, helping launch a new podcast called “What’s The Point.” She is working in the London bureau of ABC News this fall.

Jenny Luna (@J2theLuna) is a journalist who covers education and subcultures. She most recently reported for the Miami Herald and graduated from Columbia Journalism School last year, where she focused on affordable housing and immigration.

Editor’s note: In the interest of Nelson’s security, we’ve withheld his surname.