Fall 2020

Lightning Writing

– Jonathan Holloway and Richard Byrne

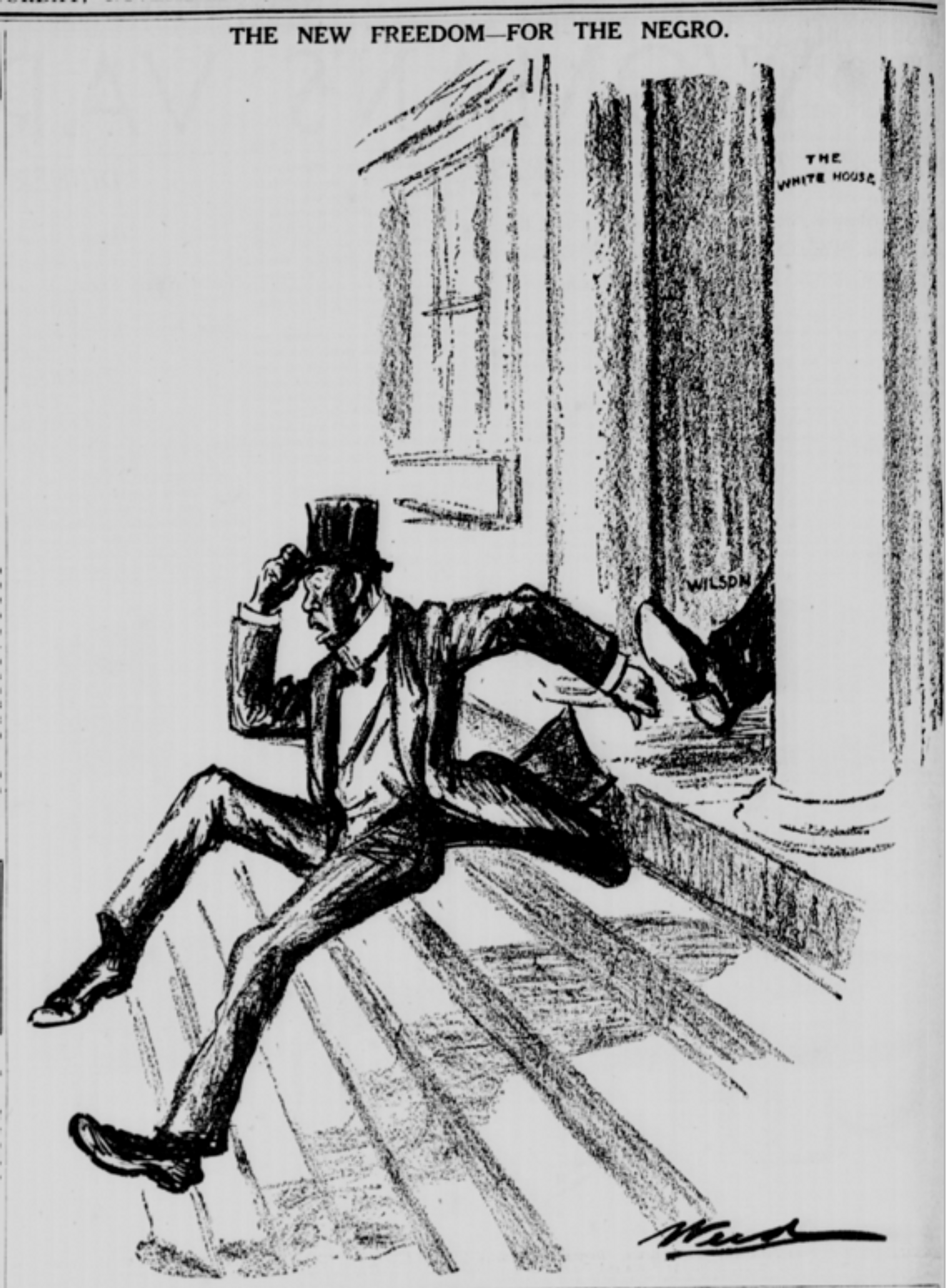

How much damage did Woodrow Wilson wreak on racial equality in the U.S.? Historian Jonathan Holloway assesses the 28th President's vexed legacy in government and academia.

When Jonathan Holloway, the Wilson Center’s 2020 Hubert H. Humphrey Fellow, gave his fellowship lecture in February on Woodrow Wilson and racial memory, he couldn’t know that the world was about to change.

A global pandemic soon fundamentally altered American life. And three months later, the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020 sparked a long-overdue racial reckoning with profound national and international implications.

Holloway’s lecture traced Wilson’s “genteel” racism through his tenure as Princeton’s president, his two terms in the White House, and beyond. The President of Rutgers University and author of books including Confronting the Veil: Abram Harris Jr., E. Franklin Frazier, and Ralph Bunche, 1919-1941 and Jim Crow Wisdom: Memory and Identity in Black America Since 1940, also forged links between the most pernicious political legacies of Wilson’s presidency and his own family history.

Holloway’s lecture traced Wilson’s “genteel” racism through his tenure as Princeton’s president, his two terms in the White House, and beyond.

A key element in “History Written in Lightning: Racial Memory, Woodrow Wilson, and the Making of the Nation” was a discussion of Princeton University’s protracted debate over the continuing presence of Wilson’s name on its buildings and programs. When Holloway gave his address, Princeton had decided to retain Wilson’s name on campus. On June 27, 2020, however, the university reversed course.

So how should we reassess Wilson in light of the evidence of his racism? Do the events of a momentous summer alter that assessment? What follows are key excerpts from Holloway’s February lecture, with additional remarks from a September conversation with Wilson Quarterly Editor Richard Byrne.

Princeton to the Oval Office

Was Woodrow Wilson’s negative impact on racial relations in the United States prefigured in his earlier tenure as the head of Princeton University?

Holloway offers Wilson’s writings on the prospects of Black students matriculating at Princeton during his presidency as Exhibit A. In 1904, Wilson wrote that “the whole temper and tradition of the place are such that no Negro has ever applied for admission, and it seems extremely unlikely that the question will ever assume a practical form.”

Wilson amplified this notion in 1909, when writing to MacArthur Sullivan, an African-American prospective applicant: “It is altogether inadvisable for a colored man to enter Princeton.”

In his lecture, Holloway noted that “[Wilson’s] racism was… genteel, and reflected a sensibility that it was not advisable to bring the races together because it would be unfair…. They would not be able to keep up with the new, more rigorous, Princeton he was creating.”

A deeper look into the historical record offers additional (and unflattering) context. Wilson's writings on the admission of Black students “were a commitment to something…insidious. In the first instance, we have Wilson quietly rewriting Princeton history. And, in the second, we find him ensuring that Princeton would remain a safe space for its white students because of his own act of erasure.”

Wilson had encountered the presence of Black students at Princeton as an undergraduate. When he was a sophomore, the university was roiled by a controversy over President James McCosh’s decision to allow Black students to audit one of his philosophy classes.

Black students also had a presence on campus during Wilson’s time as Princeton’s president. Indeed, a number of African-American scholars had taken what Wilson presumably saw as the “inadvisable” step of obtaining Master’s degrees from its Divinity School during his tenure.

“Simply put, a Black presence at Princeton was not unknown to him,” says Holloway.

“It is altogether inadvisable for a colored man to enter Princeton.”

So what was the purpose of Wilson’s erasures? “Keeping Princeton white,” argued Holloway, “meant that it would remain a safe space for students who held tightly to their presumptions that what was normative was somehow removed from a conscious political decision. Instead, it was an expression of the natural social hierarchies.”

In September, Holloway reflected further on Wilson’s Princeton tenure. “Wilson brought to Princeton – and cultivated – a certain kind of worldview,” he said. “And that worldview was one that was very homogenous. Hyper-homogeneous.” He adds that Wilson’s striving for an ideal university may have contributed to the racial atmosphere he sought to create there: “[What] Wilson was able to realize at Princeton was a sort of ideal place… A very Southern place, but a genteel Southern place, right? And Princeton is nothing if not genteel.”

In academia and in government, concluded Holloway, “I think Wilson wanted to create a space of great ideological or psychological comfort… That there is a rational order to things, and it ran along racial lines. Why not organize governance in this kind of efficient and productive way, as he saw Princeton organized?”

Promises and Betrayals

As part of his 1912 campaign for the White House, Wilson reached out to influential Black writers, journalists and clergymen, including W.E.B. DuBois, William Monroe Trotter, and Bishop Alexander Walters of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Holloway quoted Wilson’s assurances to Walters of “absolute fair dealing” with Black Americans: “My earnest wish is to see justice done them in every matter, and not merely grudging justice. My sympathy with them is long-standing.”

Indeed, Wilson’s infamous White House meeting with a delegation led by Trotter on November 12, 1914 grew contentious largely because the Black leaders sought to hold the President to his campaign promises.

But did Wilson see himself as breaking any such promises? Holloway believes that he didn’t.

“Fairness to Wilson,” he observed, “meant that local customs and practices should be preserved in order to maintain a status quo. Northern carpetbaggers, accompanied as they were with ideas that allowed Black men the right to vote, to own property, and to sue whites, were to be resisted at every turn. Fairness for Southerners like Wilson was not the kind of fairness that Black leaders in the early 20th century – much less at any point in history – sought.”

Citing groundbreaking work by University of Richmond associate professor of history Eric Yellin, Holloway described how policies enacted by Wilson and his cabinet reversed significant gains made by Black Americans, and particularly those employed by the federal government.

The damage inflicted by Wilson’s policies was extensive, yet Holloway noted that “these changes were dictated at the local level, so there was no single type of discriminatory behavior. They also happened without a paper trail, most likely because the secretaries and the department heads felt there was no need to commit to paper that which was in the natural order of things. The changes ranged from a dramatic loss of job opportunities for Blacks to the physical reorganization of workspace.”

The assault on Black Americans and their status did not stop at policy. One of the key racial flashpoints of Wilson’s presidency was his decision to screen The Birth of a Nation at the White House on February 18, 1915. The showing of D.W. Griffiths’ slanderous propaganda film, which celebrated the violent dismantling of Reconstruction, elicited furious denunciations from all corners of Black America. (Wilson’s reported observation that the film was “like writing history with lightning,” provided the title for Holloway’s lecture.)

Holloway sketched out the personal and professional relationship between Wilson and Thomas Dixon, Jr., the author of the book (The Clansman) upon which the film was based. “It’s worth noting that Dixon had remained in touch with Wilson after their time in graduate school,” he said, “and admired the segregationist policies being deployed in Washington. He wrote to Wilson directly on the matter, saying that ‘the establishment of Negro men over white women employees of the Treasury Department has, in the minds of many thoughtful men and women, long been a serious offense against the cleanness of our social life.”

Dixon also was forthright about his hopes to advance segregation with his work. Holloway quotes a letter that Dixon wrote to the President’s secretary, noting that “the real purpose of my film was to revolutionize Northern sentiments by a presentation of history that would transform every man in my audience into a good Democrat. Every man who comes out of one of our theaters as a Southern partisan for life.”

The Power of Unseen Labor

In his lecture, Holloway argued that moments in which racism obtains a public imprimatur seep into the culture itself, and lay the foundation for the policies that perpetuate inequality.

But it is not only larger cultural events such as Griffith’s infamous film that perform this work. Holloway observed that when “the mundane expression of cultural views” becomes “political positions, and, eventually, policies” it creates a loop that “fuel[s] the rearticulation of cultural views, and the process continues. A nation is shaped by this kind of process. It is born of cultural visions tied to expressions of power and policy, and all wedded to a commitment to see the world in a particular way.”

To illustrate this point, Holloway related the story of a letter of condolence written by Senator Hubert H. Humphrey to his grandmother on the death of his paternal grandfather.

That grandfather, John Holloway, had risen to a position as Captain of Waiters in the U.S. Capitol, and also had grown close to Humphrey over his career. Yet Humphrey’s letter, written four decades after the controversies of The Birth of a Nation, included a phrase (“credit to his race”) that angered Holloway’s father deeply for decades afterward.

Holloway recalled that “from time to time… Humphrey’s letter came up as an example of the party's shortsightedness, and its failure to recognize Blacks’ full and complex humanity.” His father was so angered by this letter that he once confronted Humphrey directly about his use of that phrase. (Humphrey did not remember doing so.)

“My beef was not with Humphrey,” said Holloway in September. “It was really to talk about look at this kind of mundane process [of condolence] and the way it took root as a cancer in my father's worldview. It haunted him. A letter of condolence is mundane. It's a nice thing to do. The phrasing was unfortunate. But the person who wrote the letter was reflecting a set of day-to-day practices – not just the letter writing, but the language of “credit to the race” which was very old-fashioned in the ’60s.”

Holloway concluded that “this is the danger of a cultural practice becoming mundane, and forming into a political process. It starts to wind itself up into something really concrete that you can't change. With or without protest.”

One of the key racial flashpoints of Wilson’s presidency was his decision to screen The Birth of a Nation at the White House.

The lecture also linked the labor of Holloway’s grandfather in the halls of the U.S. Congress to the unseen labor that sustains every institution – including the Princeton University that shaped Woodrow Wilson.

Princeton’s campus report on Wilson’s legacy, for instance, focused largely on the experiences of students and faculty. “If Princeton aims to wrestle with the complexities in his own past,” Holloway said in February, “it would do well to have an honest reckoning of the unacknowledged work that literally built the university and kept it running. This was work that Wilson would not have recognized at Princeton, or when he was in the White House. Indeed, one of the difficult truths about Woodrow Wilson's legacy is that his decisions shaped a world around him that he never saw and did not deign to imagine.”

As he began work as President of Rutgers, Holloway found deeper reasons to reflect on this connection: “If you don't have dining hall workers, custodians, groundskeepers, and plumbers, you won't have a university. It won't function, right?”

Holloway added that “people want to be acknowledged…. And they want to be heard, which is quite different than being acknowledged. If leaders take the time to acknowledge their workforce in that way – the people doing ‘the real work,’ the ugly work., the messy work. Take the time to say: ‘You're really important to me. Tell me your story.” You would see a radical change for the better, I think.”

Reassessing Wilson

If Wilson’s time at Princeton was indeed a prologue to his presidency, the university also has been the site of the fiercest battle yet over his legacy. In February, Holloway observed that Princeton’s struggle “wasn't just about Woodrow Wilson. His name was merely the most prominent and easily attached to a set of values that the university no longer admired….The Wilson Legacy Review Committee acknowledged this dynamic, and made it clear that it was committed to a university that was diverse, welcoming, and inclusive.

“While the committee ultimately recommended that Wilson's name remain attached to the various buildings and awards,” he continued, “it declared that Princeton was obliged to be a better and more honest steward of its own history – acknowledging the complexity of Wilson's legacies, and particularly those aspects of his worldview that were no longer aligned with the university's values.”

Princeton’s June reversal of its decision on Wilson made national headlines. In September, Holloway offered his reaction. “In an ideal world,” he said, “institutions would look at their own past without being pushed to do so.” Yet Holloway praised Princeton for “doing the work” past mere recognition of a problem.

“The first part is acknowledging it,” he noted. “The second part is: ‘We've identified the fact that our predecessors made decisions that are ethically unrecognizable to us… What are we going to do now? That is part of our history. We own it as part of history. But we are not captive to it. We must do something better.’”

Holloway hoped Princeton would “stand firm in that project. It's important. It's important in how you build a better citizen. All of us need to have the capacity to say, ‘these are my beliefs’ and to say, ‘that thing I thought before was wrong.’” That is speaking to our humanity, and our capacity to become better people, so we shouldn't be denied that opportunity.”

Reflecting on his exploration of Wilson and his racial legacy, Holloway drew a parallel to how historians should approach Martin Luther King, Jr. “He was accomplished in all the ways we already know,” he said. “But not a perfect person…. Some people say: ‘Well, why does anybody need to talk about that? Look at all the great things he did.’ But I think you need to talk about it. Not a in lascivious way. But we need to talk about it because he was flawed, and that makes his exceptional work that much more exceptional.”

“In an ideal world, institutions would look at their own past without being pushed to do so.”

In our own moment, Wilson presents a much more vexing case. “Would I ever have been invited to give a lecture if it was up to Wilson? That’s kind of hard to imagine,” Holloway continued. “Would he have been skeptical of my rise in higher education? Probably. Or he might have seen me as so exceptional that it broke the rules…. Either way, we wouldn't have been buddies.”

Yet Holloway urged that “we need to be respectful of the complex humanity” of historical personages. Wilson “did important things that improved institutions,” he continued. “He had a vision for making the world a better place.” Historians must square that with a view to Wilson’s pernicious legacy on race, which echoed loudly in his own century and beyond.

“People, especially very public people, are usually frozen in time, “ he observed. “Their humanity is stripped away in that process. They are subject either to praise which renders them like a statue, or as a political tide shifts now, they're built into a villain. But most people aren't simply praiseworthy, or simply villainous. They are a kind of a mixture of these things.”

At bottom, observed Holloway, “historians are trying to capture the full humanity of somebody. Everybody deserves their full humanity being rendered…. Wilson's clearly an important person. You can't argue that. And that’s what Princeton was saying: “We're going to keep some things because he's a really important person to our history. Of course he was. But we are not going to be unafraid of saying he was important, but he was flawed.”

At the end of the September interview, Holloway offered a coda to one key element in his lecture. While he knew of his father’s anger at the letter of condolence, he only recently discovered that Humphrey and his grandfather were closer than he had realized. Indeed, Humphrey had quietly made arrangements to pay for John Holloway’s funeral.

The new information not only offered new context for the relationship, said Holloway, but deepened his own questions about his father’s response. “When you discover these things,” he said, “ you see them in a different light.”

Cover image: Woodrow Wilson, 1923. (Library of Congress)